Last summer, The New York Times published a profile on a practice called “rewilding.” It’s a nauseating concept; if you’re eating food right now, either spit it out or close your laptop. A subsection of rogue scientists has started visiting some of the world’s last “untouched peoples,” and specifically the Hadza tribe in Tanzania — which has patrolled the East African Rift for thousands of years — to stage gonzo experiments with local stool.

Yeah. You read that right. Here’s the moneymaker from the article: “As the sun set in Tanzania on a September evening in 2014, Jeff Leach inserted a turkey baster filled with another man’s feces into his rectum and squeezed the bulb.”

The stated goal of these unseemly missions is to mitigate (and reverse) the damage that industrialized living has inflicted on the intestinal microbiome. Prehistoric people, the thinking goes, had stronger and more diverse guts, which allowed them to subsist on high-fiber diets — the sort of diets that some of us reach for by consuming large amounts of beans, berries and cruciferous vegetables, which inevitably induce pain and disfunction in the gastrointestinal tract. From an evolutionary perspective, we’re not equipped to process that much fiber anymore.

The microbiome, similar to the brain, the deep ocean and outer space, is a mysterious realm that’s deserving of research an exploration. But there’s a better way to go about it than sampling the excrement of an impoverished indigenous community. This sort of “bacterial supplementation” isn’t just junk science; it’s yet another example of our unhealthy and inappropriate obsession with the lives of modern hunter-gatherers.

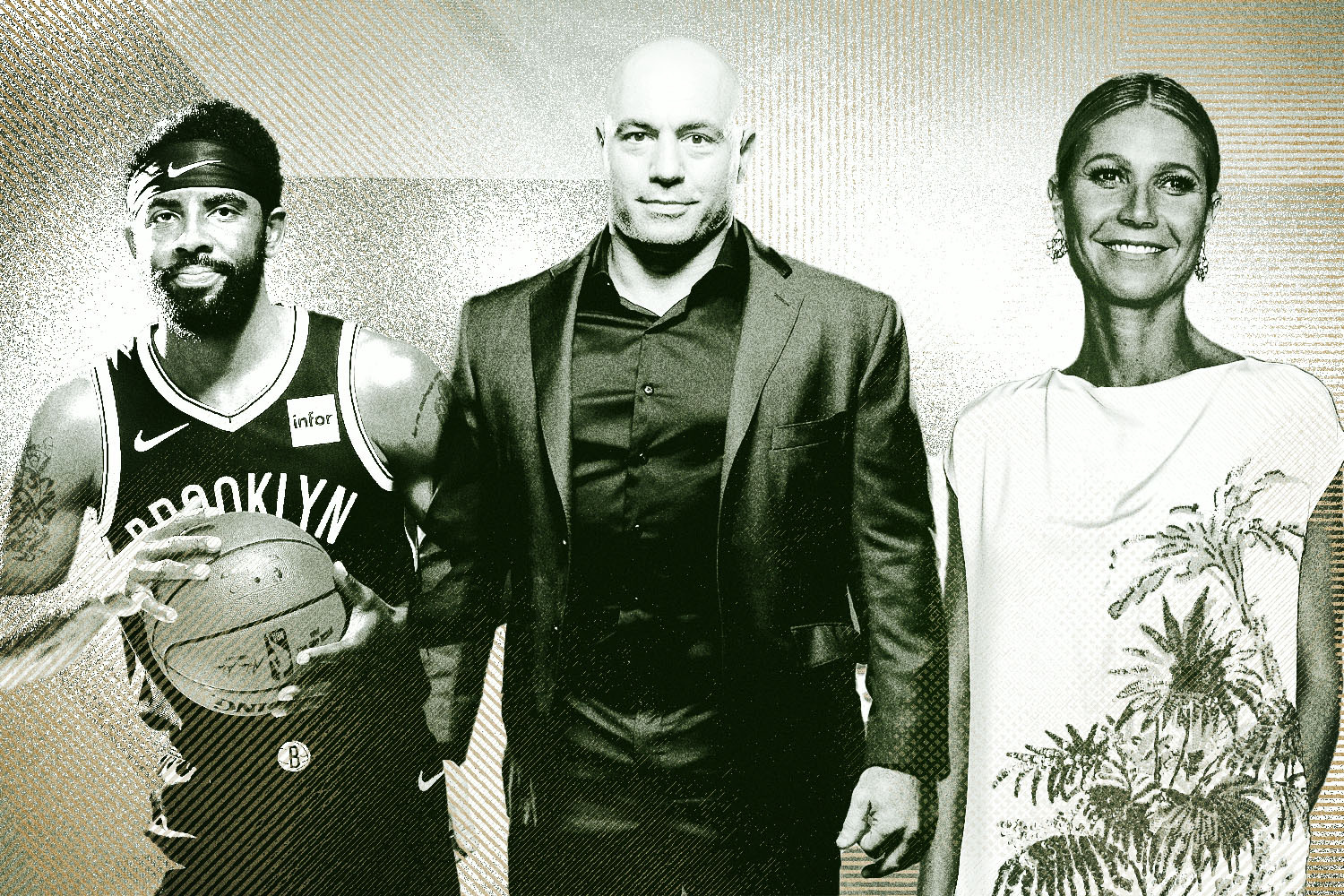

Too many of today’s Instagram influencers, fitness-brand founders and self-anointed “researchers” harbor a misplaced romanticism for the lifestyle habits of yore. The general thesis: prehistoric people did it right, and we screwed everything up. Disciples of ancestral living follow the popular Paleolithic diet (with some going as far as to consume raw organs), eschew vaccines or basic medical treatment and believe natural contact with the soil and the sun supercharges their electrons.

There are two key issues here. For one, while it’s easy to make an argument against modern living (between smoking, alcohol, processed foods and screen abuse, we’ve gotten extremely good at killing ourselves), paleo-heads tend to prescribe solutions that are 12,000 years in the wrong direction, as if living exactly like our forebears is really the correct path forward. Second, in order to make this point, online personalities routinely fetishize the Hadza people, broadcasting them across social media as a form of primitive show and tell.

I hunted, killed, and ate a wild baboon (brains and all) with the indigenous Hadza tribe in Africa.

— Anthony Gustin (@dranthonygustin) March 24, 2022

Here are the 13 things I learned about human health along the way.

👇 THREAD pic.twitter.com/OXmUz85JPm

It’s important to note that threads like the one linked above, from Anthony Gustin, the CEO of a keto snacks company, do have some merit. Gustin spent some time with the Hadza and reached a few notable conclusions:

- Hunting is no longer bountiful

- Their diets are less high-fiber than you’d think

- The Hadza don’t get particularly stressed

- Their field skills are untouchable

- They use every part of an animal

- A honeycomb is considered a huge prize

Interwoven within these observations, though, are hot takes and unsolicited editorials that A) propagate our voguish infatuation with ancestral living and B) relegate the Hadza people to a role of study-things, from which we should adopt (appropriate) certain lifestyle habits to improve our miserable American existence.

For instance, Gustin lampoons “chubby modern humans beating their joints up jogging on pavement for hours on end for ‘cardio,’” while the Hadza rely primarily on a combination of walking and sprinting. He also claims “water is overrated,” and links their lack of water consumption with their “high energy” and “lack of chronic disease.” For good measure, he asserts “we have no practical skills” and “Americans eat fast, alone and in front of screens,” in opposition to the Hadza, who “can start a fire in under a minute,” and “eat slow, in communion.”

None of those takes are completely out of left field. But that isn’t really the point here. This sort of primordial tourism, which is quickly becoming a bucket list item for fitness influencers — the notorious Texan who goes by the name “Liver King,” owner of 1.3 million followers, visited the Hadza last week — seems a bit too comfortable moving past objective, third-person reflection, to active, first-person reprimand. And for too many online, it probably ends up reading like a pitch.

It’s comforting, at least, that Gustin took time to emphasize the Hadza’s laidback sense of community (he references their penchant for storytelling and laughter), but what of drinking mud-water and eating larvae? And what are we supposed to make of his overarching intentions when the thread’s initial tweet reads: “I HUNTED, KILLED, AND ATE A WILD BABOON (BRAINS AND ALL) WITH THE INDIGENOUS HADZA TRIBE IN AFRICA.”

Visitors to the Hadza tend to exchange trifling gifts in exchange for their hospitality and guidance. But what benefit do the Hadza gain when their lifestyle and likenesses are posted all over social media? If, say, fecal transplant research led to a major windfall and launched a series of rewild-focused biotech brands (it won’t) would these people ever see a cent? (They wouldn’t.) A similar criticism could be lobbed at the founders and influencers flying to meet these “untouched” people — during a pandemic, mind you — to earn Hemingway-esque clout amongst their followers. Perhaps, if a tribe chooses to live cut off from civilization… civilization should respect that?

To be fair, there has been some significant, groundbreaking research involving the Hadza people. Their lifestyle is a walking, talking time machine, and has proved an invaluable asset to paleoanthropologists and evolutionary biologists like Duke’s Dr. Herman Pontzer, whose book Burn blew the lid off conventional metabolic research last year, or Harvard’s Dr. Daniel Lieberman (known best for his “born to run” thesis, which concluded that Homo sapiens are natural distance runners), who recently published the “active grandparent hypothesis.”

For those of us not publishing celebrated field research, though, it’s important to be realistic. There is no reasonable parallel between the day-to-day of the Hadza people and the 83% of the U.S. population that lives in urban areas. Propping up prehistoric people as the Platonic ideal of behavior is tired and unfair — both to the tribe in question, and the rest of us scrolling through Twitter. Modern living, for better or worse, comes with some sticking points. Many are biologically inconvenient, like drugs, potato chips and long hours on laptops. But many others, like our access to education, art, tools, travel, foreign places, you name it, shouldn’t be taken for granted.

There is plenty of room within the scrum of modernity to find a healthy life that’s worth living. So please, please leave the old ways to those who know them best.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.