Warning: this article contains major spoilers for Squid Game.

By now, you’ve probably already seen Netflix’s Squid Game — or at least been told you need to by one of the millions of people worldwide who have already binged the South Korean survival drama. The show is currently the streaming service’s No. 1 show in 90 different countries, and it’s on pace to eclipse Bridgerton as its most popular series of all time. It’s so popular in its home country that South Korean internet service provider SK Broadband has even sued Netflix over the surge in network traffic caused by fans streaming the series.

But in case you’ve somehow managed to escape the premise of the hyperviolent, often-upsetting series, a quick summary: 456 people who are all living in poverty or buried in massive debt are presented with a mysterious offer to play a game and win some money (4.56 billion won — or roughly $38 million — they later learn). The players include our protagonist Seong Gi-hun, a gambling addict who lives with his mother and struggles to support his daughter; his childhood friend Cho Sang-woo, the head of an investment team at a securities company who is wanted by police for embezzling from his clients; Kang Sae-byeok, a North Korean defector looking to smuggle her parents out of the country and get her brother out of an orphanage; Oh Il-nam, an old man with a brain tumor; Jang Deok-su, a gangster with a lot of gambling debt; and Abdul Ali, a Pakistani immigrant whose boss has been withholding his salary for months.

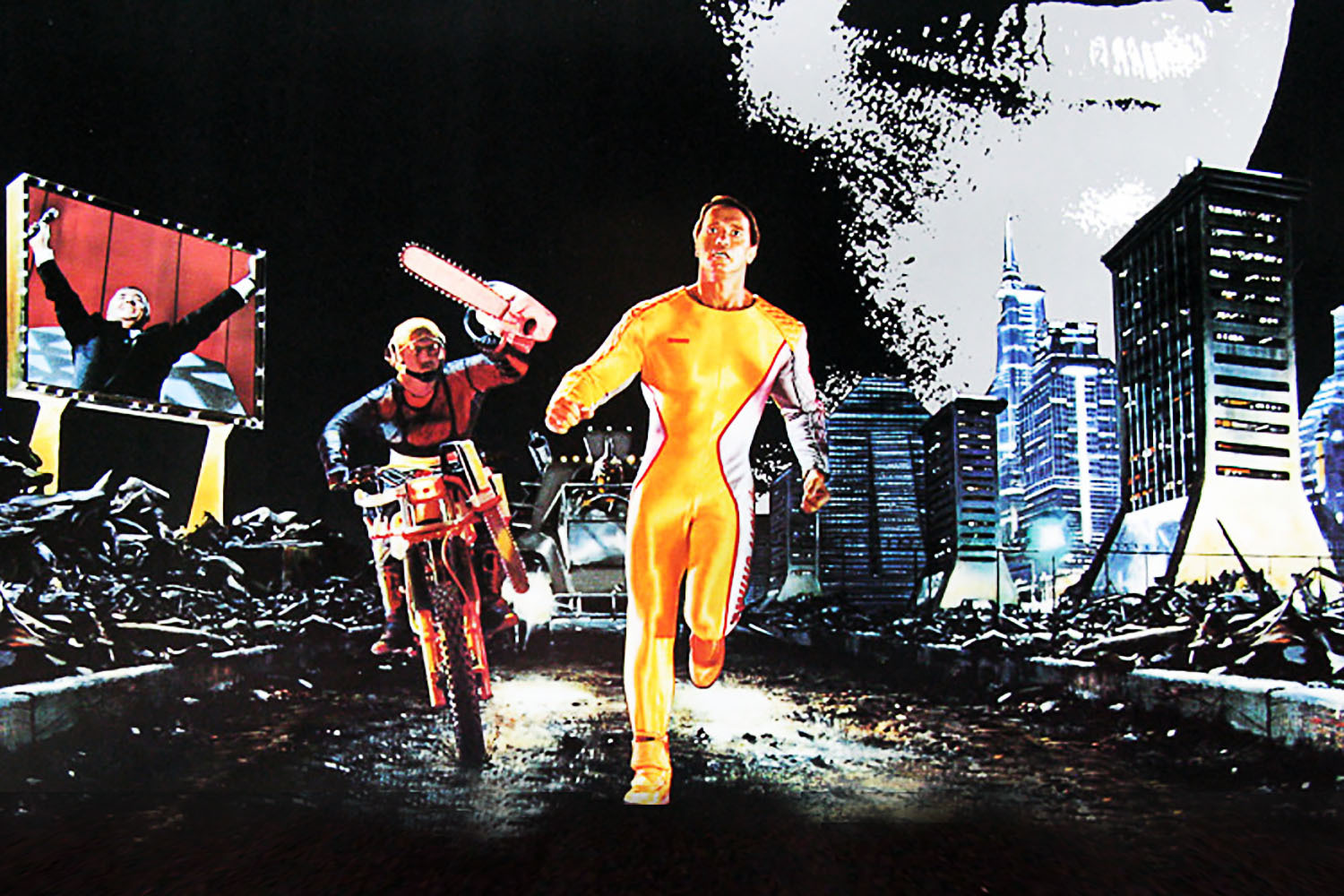

The players are told they’ll be competing in a series of children’s playground games, like tug-of-war and marbles. The winners of each game advance to the next round, and the losers are eliminated, quite literally. Unaware what exactly they signed up for, more than half the original 456 contestants are gunned down during the opening game of Red Light, Green Light. Those who survive are horrified and demand to leave. A vote over whether or not to stop the tournament is held, and ultimately they’re all released with an invitation to pick back up again if they so choose. After returning to their real-life struggles, more than half of them decide to return to the deadly game, gambling their lives for a slim chance at a big payday.

There’s no doubt that since it debuted on Sept. 17, Squid Game is resonating with people across the globe in a big way for its social commentary about class and the ways that the poor are often made to degrade or endanger themselves in order to survive. Towards the back end of the series, we’re introduced to the masked “VIPs,” wealthy patrons who place bets on the games and watch for their own amusement. But by devoting so much time to the twisted, age-old “bored rich people make poor people fight to the death for their own entertainment” trope, is Squid Game actually doing the same thing it criticizes its villains for doing? Can we really fault the Front Man, the game’s masked ringleader, for sitting back and drinking a Scotch and leering at the carnage unfolding on a screen when we’re essentially doing the same thing?

Squid Game doesn’t glamorize its violence — the camera rarely moves away from its grisly scenes, forcing viewers to confront what a Hunger Games-style fight to the death really entails — but it does rely heavily on it. There’s character development, of course, as well as plenty of drama that unfolds outside of the games to highlight the ways people will lie, cheat or even kill to ensure their own survival. But the games are the driving force behind the series, and they’re often excruciating. In one particularly cruel round, players are told to partner up, and they all select their closest friends or allies in the game, thinking they’ll be playing together; they soon find out they’ll be playing marbles against their partner, and the loser will be killed. One man beats his wife in the sick game, and after she’s executed, he kills himself.

Scenes like that are meant to illustrate the difficult predicament the players find themselves in, but the show’s big twist doesn’t do much to drive home the fact that they have no choice but to compete with their lives for a one-in-several-hundred chance at millions of dollars. Eventually, through a series of circumstances we won’t get into here, Gi-hun is crowned the winner. Disgusted by what he had to do to win, he doesn’t touch his prize money for a year, but he’s finally contacted by Il-nam, whose death was faked during the tournament. It turns out Il-nam — who is dying of a brain tumor, albeit much more slowly than anyone might have assumed — was the mastermind behind the whole murderous game; it’s a fairly obvious twist, given that we see the seemingly genteel old man grinning and happily participating during that first game of Red Light, Green Light while everyone’s getting slaughtered, and it doesn’t deliver much in terms of making any kind of significant point about class. Il-nam claims he orchestrated the whole game, which we learn at one point has been taking place annually for over 30 years, because both the poor and the ultra-wealthy lead monotonous lives. He was simply trying to derive a little pleasure out of his boring life as an obscenely rich guy, and when he was diagnosed with cancer, he decided it’d be fun to participate in the game himself. (Of course, the stakes are much lower when you’re the mastermind and aren’t actually killed for losing.)

Making this semi-sympathetic character the one behind this unbelievably cruel setup is perhaps some form of commentary on how.capitalism has turned all of us — even the nice, sick old men — into villains, but it ultimately takes the wind out of the show’s sails. He points out to Gi-hun that the contestants who returned after being granted the opportunity to leave weren’t just willing to risk their own lives for a shot at a large amount of cash — they were knowingly sacrificing the lives of hundreds of other people, knowing that in the best-case scenario, they’d walk away with the grand prize after everyone else was executed.

What point, exactly, is this meant to drive home? That when backed into a corner, humans revert to our animal instincts and we’re willing to do whatever it takes — even offer others up for slaughter — to survive? That’s an important point, but it’s also a fairly obvious one; we saw it in the first episode when panicked competitors were stepping on the bodies of those who had been shot as they scrambled to make it across the finish line. Why drag it out for nine episodes when it’s something that seems so inherent? The only reason this was a nine-hour TV series (which, by all accounts, seems primed for a second season) instead of a movie is that writer/director Hwang Dong-hyuk decided we needed to spend hours gawking at the poor as they kill each other and die for a chance at bringing home some money.

Squid Game has good intentions, but the way it executes them (no pun intended) makes us no better than the wealthy VIPs, hedging bets on who will survive. With every twist and turn, we’re riveted — and that’s the problem. Exploiting the poor shouldn’t be entertainment, and when we’re plowing through a show as fast as we can to find out what horrors these characters will be subjected to next, that’s exactly what it is.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.