Welcome to The Workout From Home Diaries. Throughout our national self-isolation period, we’ll be sharing single-exercise deep dives, offbeat belly-busters and general get-off-the-couch inspiration that doesn’t require a visit to your (likely now-shuttered) local gym.

In 2010, Harvard paleoanthropologist Dr. Daniel Lieberman started running outside without any shoes on. Not across a turfed athletic field, nor through Cambridge Common, but directly atop the city’s red-brick sidewalks and concrete streets. In spite of the confused stares, Dr. Lieberman had good reason to believe that the practice was good for him; he’d studied the evolution of the human body for decades, and was in the midst of publishing an article in Nature with research partner Madhusudhan Venkadesan — alongside a team of six additional researchers — that challenged supposed, time-tested wisdom that we all need running shoes in order to run.

Dr. Lieberman had begun with an important query: If cushy running shoes had only been around since the 1970s, when Americans collectively learned to jog and a Beaverton brand named Blue Ribbon Sports officially changed its name to Nike, Inc., how then should we qualify all the running that came before their introduction? Were all those barefoot, or barely-supported miles, which were run by millions of people for millions of years (and are still run, in many parts of the modern world) inherently ill-advised or injurious?

His findings, which helped fuel a barefoot running craze for at least the ensuing half-decade, suggested just the opposite. Contrasting shod (shoe-wearing) runners in America, with those who’d run barefoot their entire lives in Kenya — while also testing for recently shod Kenyans, and habitually barefoot Americans, across all ages — Lieberman’s team was able to cross-reference contemporary biological mechanics with our understanding of hunting habits at the rise of the Anthropocene.

Around two million years ago, as Africa’s jungles gradually became savannas, humans learned to catch quadrupeds by simply tiring them out; 15 to 20 minutes of running was usually enough time. It was a reliable way to guarantee a steady food source, and reigned for well over a million years, in grasslands around the planet, until the Neolithic Revolution arrived, at which point Homo sapiens roundly domesticated animals and wheat and began building homes and inventing complex social constructs like realms, currency and religion. The crucial detail there, though, is that humans relied on running for a really long time. If running without shoes had unilaterally led to pre-historic torn ACLs and stress fractures, human beings probably wouldn’t have prioritized running for a millennium in their evolutionary process, and they certainly wouldn’t have done so for over a million years.

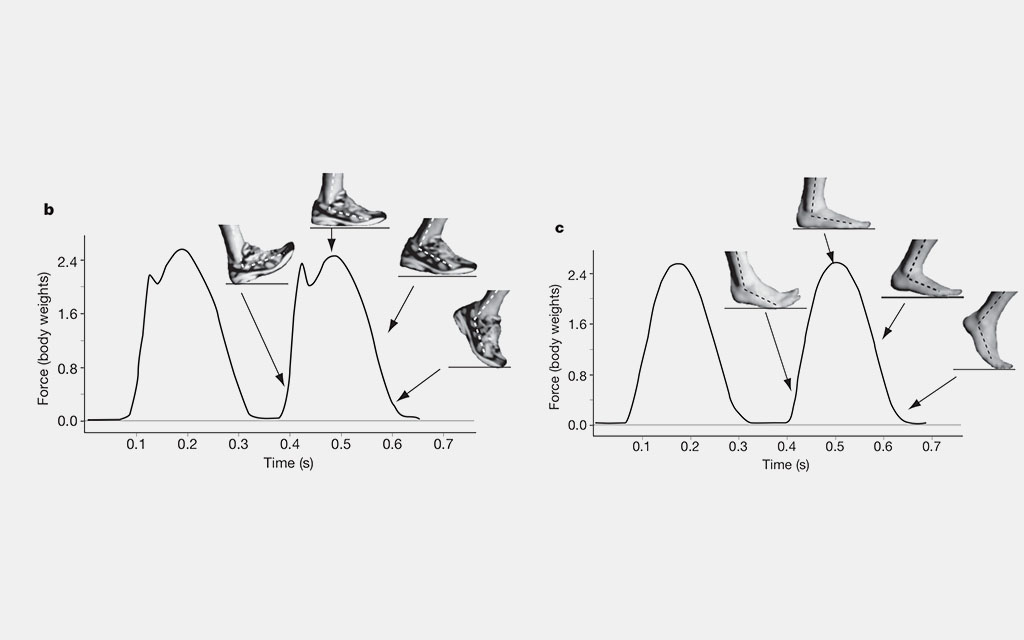

Dr. Lieberman applied that knowledge to his research, which revealed that habitually barefoot runners were often fore-foot strikers, while shod runners were mainly rear-foot strikers. These terms refer to how the foot meets the ground:

In simpler terms, those who were used to running in cushy shoes tended to land on their heels first; and those who didn’t landed in a toe-to-heel motion. Early humans, who of course didn’t own Nike Joyrides or Adidas Ultraboosts, would’ve naturally gravitated to a fore-foot strike, because there is simply nothing beneficial to landing directly on your heel. From the armchair scientist’s perspective, it just looks painful. It doesn’t pass the eye-test. From an advanced biological lens, it’s all a matter of angles. Landing straight down on a heel leaves nowhere to transfer energy. There’s no way to recycle all that force you’re driving down into the ground. You may still be running, but that particular strike has come to a dead stop. Coming in at an angle, though, allows for “rotational energy,” which propels you forward with more efficiency.

The running world latched onto these findings, hard. Christopher McDougall’s Born to Run, which documented the ultra running lifestyle of the Tarahumara Native Mexican tribe, sold three million copies in the early 2010s. McDougall was stunned by the tribe’s ability to avoid injury, despite running distances of over 100 miles in sandals, and, similar to Dr. Lieberman, argued that bouncy, skyscraper running shoes were part of the problem, an effort by running brands to coddle improper mechanics, and tacitly tolerate rear-foot striking, which led to repetitive stress injuries in the soft tissues at the bottom of the foot, or impact damage in the shins.

People were bothered enough by that information to help anoint an alternative subset of athletic footwear — the zero-drop running shoe. A shoe’s “drop” refers to the difference in stack height from the rear foot to the forefoot. In order to soften the blow of repeated heel-striking, it’s common for the heel section to be built up higher than the rest of the shoe by as much as 12 or 14 millimeters. It doesn’t sound like much, but certain research suggested it was encouraging bad form that ultimately made us more susceptible to injury. Remember Vibram, and their zero-drop scuba diver runners? They took on the brunt of the jokes from non-believers, and while they’ve since fallen out of favor, they helped usher in the low-drop era we’re in to this day, when sub-8mm drop running shoes are commonplace from all the popular brands.

I can remember a couple summers, too, where my track coaches suddenly encouraged us to take our shoes off and head down the grass to run straight-aways. There was a general, lazily-researched vibe hanging around the running world that training barefoot did … something, and it was probably a good idea to reap its benefits once in a while. Fast-forward a decade, though, and the “trend” — if you can call a million-year-old-plus practice that — has lost some momentum and mojo. Research came out in 2013 that running in Vibram footwear leads to a greater risk of foot bone injury, and while barefoot running isn’t uncommon to see on the beach or a turf field, the thrill of Dr. Lieberman and Christopher McDougall’s discoveries has been firmly replaced by other alluring stories in the running world — one of which, ironically, concerns the uncommon height and energy return of a cushioned heel: Nike’s Vaporfly 4%, which helped Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge break the unthinkable two-hour marathon barrier last year.

It would be incorrect, though, to crown cushioned running shoes the victor in some battle, since 1972, between barefoot runners and shod runners. Particularly if there is a battle, it’s a personal one, taking place within each runner’s precise, and more than likely incorrect, mechanics. A runner like Eliud Kipchoge benefits from the Vaporfly’s Pebax sole, which allegedly delivers 30% more energy foam than racing shoes of decades past, but to run world-record-level marathons year in and year out he also must run properly. A cushioned, energy-giving shoe, then, is only an additional tool in the shed, on top of the most important — running with a safe, fore-foot strike, the way humans are supposed to run, and did run, for much of their existence.

You can do it too, and you don’t need to worry about shoes that look like the webbed feet of a duck or racing trainers that look like moonboots. You just need a pair of feet, and a reasonably (preferably recently) paved road, where pebbles and sticks are at a minimum. Practice running back and forth on the concrete, and notice, once your feet adjust to the shock of performing something so out of the usual, how they naturally adjust. They don’t want pain, they do want maximum energy transfer, and they will prioritize striking from the front. My coaches had the right idea, getting us to take off our shoes, but sending us to the grass defeated the purpose. On soft grass, laced with rubber pellets or soil, the heel can continue to lead, guaranteed a soft landing. On hardened cement, they’ll be forced into proper running mechanics.

The idea is to take it slow. Those Vibram folks started hurting their bones because they treated their new, prized shoes like the rest of the running trainers in their closets and immediately started logging similar mileage without learning to transition to a healthy, forefoot striking method. I would recommend interspersing barefoot, pavement straight-aways (think distances of 100-250 meters, run close to 75% effort) with your regular running routine. Then, over the long distances with your shoes tied tight, think about how you’re striking the ground. It the age of COVID-19, the streets are relatively bare. But even if a couple shocked stares come your way, don’t worry. Better to stress over what the neighbors think than head to the doctor with a stress fracture.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.