Among Fernando Alonso’s many accomplishments — he’s won two Formula One World Drivers’ Championships, has 32 Grand Prix wins and is the erstwhile holder of almost every “youngest driver” record — the 40-year-old Spaniard also once cracked a nut with his neck.

It’s true. Check it out here, in all its grainy, 2009 glory. It’s unclear exactly what sort of nut he cracked (a walnut?) but it doesn’t really matter. His oxen neck splits it in two as if it were an egg. In the comments section, diehard F1 fans sarcastically invoke a refrain commonly uttered by those who don’t believe in the physical rigors of motorsport: “They’re not athletes, they just sit in a car and drive.”

Netflix’s smash series Formula 1: Drive to Survive has done yeoman’s work in icing that trite take. According to Audiense Resources, American interest in motorsport’s highest class of international racing is up a dramatic 56% since 2020. The all-access show (which released its fourth season a few weeks ago), is a massive reason why, affording viewers the opportunity to explore every aspect of the sport.

There are some undeniable conclusions right there on the screen. One of the biggest? These guys are athletes. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Consider:

- During a race, a driver’s heart rate soars up to 170-180 beats per minute and will stay in that range for two hours. That’s almost identical to what the world’s top marathoners ask of their hearts during competition.

- F1 drivers lose an average of 47 ounces of sweat while racing, shedding over three pounds of water weight. That number only goes up when they compete in extremely humid locales like Bahrain, Malaysia or Singapore.

- The G-force acting on drivers is remarkable; they need strong cores to counteract 6.5g in lateral turns, have to exert up to 175 pounds of their own force to brake at various times in a race and experience loads on their necks up to six times the weight of their head while cornering — hence, a neck strong enough to crack a nut.

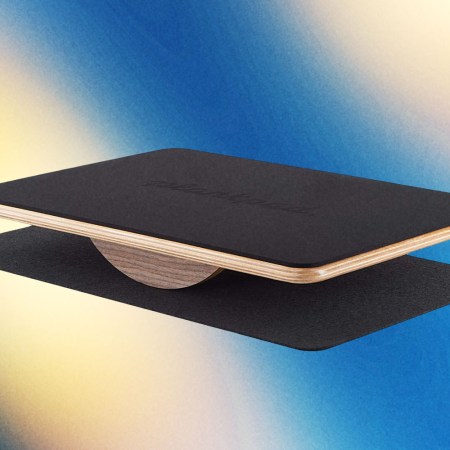

There are all sorts of other fun stories out there where drivers prove they’re world-class athletes. Like Lewis Hamilton registering a Batak score (a machine that tests one’s reaction time) better than the Belgium national soccer team’s goalkeeper, or Jensen Button holding his own against Olympic triathletes, or Heikki Kovalainen getting his arms into “steering wheel shape” by sitting on an exercise ball and holding a seven-pound weight in front of his chest for long periods of time, shifting it left or right at the whims of his trainer.

Point is, we’re not only past the debate of whether motorsport athletes are athletes — we should be proactively looking to study their training, and copycat some of their most creative progressions into our own regimens. One driver certainly worth learning from is Phil Hanson, a 22-year-old Brit who competes in the FIA World Endurance Championship and won the outright title in 2020, when he also finished first at the infamous Le Mans 24.

So. What sort of shape does one need to be in to operate a 2,000 pound automotive for 1,000 miles? Hanson finds it easier to explain what driving feels like when you’re not in shape.

“Every driver knows what it feels like when your neck gives up. There’s nothing worse than that point of fatigue, because once your neck’s gone, there’s no coming back. Every time you corner from that point onward it’s a fight to keep your head up instead of resting it against the headrest… [And] it’s not always your neck that gives up, quite often it can be your lower back, or lumbar, or core, or glutes. If there’s a weakness, the car will find it. If and when it does, concentration becomes twice as difficult, because now instead of thinking about the lap, traffic, or balance of the car, you’re thinking about the pain in your glutes that has been cramping up for the past 10 minutes. And you still have an hour left in the car.”

In the interest of not flailing around like a rag doll while driving 210 mph, Hanson observes a rigorous workout routine, which surprisingly doesn’t change much from offseason to season. He works out Monday through Wednesday and Friday and Saturday, with rest days on Thursday and Sunday, although one rest day is usually an “active rest,” populated with low-impact cardio (45 minutes on a spin bike). On days he’s getting after it, he’ll turn to high intensity intervals, foundational full-body strength exercises and mobility work.

Plus, somewhat rare for a driver, Hanson dabbles in CrossFit: “Many racing drivers cycle, some run, some do more strength training than others. Everyone has some kind of individual difference about their training. For me, I’m one of the few that does CrossFit. I find it’s what works the best for me in the style of programming and foundational layout of a workout. I don’t do your regular CrossFit classes, though. I have a program designed around my needs and necessities.”

Hanson can readily identify his pillars of athletic success — performance, health and longevity — but he’s wary of attributing victories on the track solely to physical fitness. Peak physical condition is “required” in motorsport, he acknowledges, but its ultimate value is in fortifying mental fitness. “For the most part, motorsport is a mental game of concentration. Lapses in judgement are compounded by the high-pressure environment of a race. An inability to stay focused in a mentally fatigued state can prove disastrous. The gym is the place to strengthen these areas, whether it’s during high intensity intervals or long endurance cycles. It’s often when I am in a deep physical slump that it’s me vs. me, me vs. my mind. During these sessions I make progress with my mental resilience.”

Matthew Scholtz also competes in motorsport, only he races a superbike in the AMA Superbike Series, a road motorcyle league promoted by MotoAmerica. It’s an entirely different sport, with its own unique rigors — check out how preposterously close Scholtz gets to the ground while turning the bike; his elbow nearly grazes the cement — but the dedication to training remains the same. Scholtz reports regular bouts of heavy weightlifting, kickboxing, rowing and swimming, plus a daily dose of stretching. His sample workout includes rounds of push-ups to failure, pull-ups to failure, shoulder presses, weighted lunges, kettlebell swings, low row back pulls and leg presses.

Strength exercises, all, but brawn isn’t necessarily good for business. Scholtz is in pursuit of lean, plucky mass, the sort that will help him keep his bucking, 200-pound bike under control, without weighing it down (and thereby slowing him down).

Above all, he champions cardio. He aims for up to an hour each day. “If you aren’t in good shape on the track, your heart rate is the telltale sign,” he says. “You’ll end up breathing really heavily, which tends to take your mind off of your speed and hitting your marks… I’m always focused on building up my cardio to avoid fatigue during races. It’s all about maintaining a steady state.”

While Hanson can’t exactly practice his craft by taking a Tesla out on the freeway, Scholtz is constantly putting in hours on other types of bikes — he spends 90 minutes a day on a mountain bike, and he cross-trains by riding motocross. “It’s the closest thing to riding a superbike. I can pack up my bike, head into the track, put 25 dollars of fuel in it and ride. Sometimes I’ll have my wife time me as I do laps. Every time I want to go ride my superbike it costs thousands of dollars to clean off the track and reserve the track for training. I started racing motocross when I was eight, and got into superbike racing when I was 14. All three top MotoAmerica riders from last year, including myself, have a heavy motocross upbringing and background. It’s the closest you can get to replicating a superbike as far as the focus on throttle connection when sliding and how the bike is talking to you as you’re riding.”

One aspect thing that endurance drivers, superbike stars and all the F1 legends have in common is an appreciation for nutrition and recovery. Scholtz says he prioritizes healthy foods, hydration and lots of sleep.”I listen to my body when I feel tired. If that means taking a day or two to rest and recover, I’ll do that. I also can’t stress enough the importance of stretching each day. I also get a lot of soft tissue massages, do cupping and use muscle guns to loosen up any tightness.” Hanson adds a daily cold shower, plus habitual sessions in a 50-degree plunge pool. Such luxuries can feel far away amidst the mire of a hellish race, but he manages.

“During a race, I’m not given the virtue of 10 hours of sleep. At Le Mans, for example, I might only be able to get away for 45 minutes of sleep at a time, and a full meal won’t exactly help me wake up feeling ready to jump in the car at over 210mph at three in the morning either. A sports masseuse at the track can work wonders to prevent muscle soreness, though, and help flush out lactic acid directly after coming out of the car. I also rely on fast-absorbing glycogen gels and BCAA powders to stay sharp for the the full 24 hour race.”

What of tomorrow’s stars? To what extent should young motorsport athletes be prioritizing physical prowess? Look to any mainstream recruiting sport — with invite-only camps and “big boards” that rank 14-year-olds — and you’ll find intricate, intense weekly regimens that start as early as middle school. Wouldn’t it be prudent for those who’ll be driving racing cars and superbikes in the 2030s to get as fit as possible, as soon as possible?

Scholtz doesn’t think so. “For the younger guys and girls competing in MotoAmerica or any other motorsport, I would say it’s more about mastering the mechanics of the motorbike,” he says. “Learn what makes you quick on the bike and what you need to do to maneuver it on the track. Understanding the bike is far more important at a young age than any physical fitness.” Besides, this is supposed to be fun. “As a kid, you shouldn’t have to take it so seriously. The majority of kids competing on our circuit are still in school, playing other sports and being kids. They don’t have all day to train like I do as a professional. That’s how it should be. They should keep it fun and work on their racing craft.”

In other words: there’s plenty of time to build up those necks.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.