Nick Butter Ran 196 Marathons in 22 Months. Here’s What He Learned.

On January 6th, 2018, British runner Nick Butter took the first steps of a marathon in Toronto, Ontario. Six hundred and seventy-five days later, he crossed the finish line of a different marathon in Athens, Greece. In between? One hundred and ninety-four other marathons, making Butter the first human in history to complete a marathon in every single one of the world’s 196 UN-recognized countries. For charity, no less.

Over those 22 months, Butter logged more than 400 flights (that’s an average of four a week, for anyone counting), accrued nine passports and went through 15 pairs of trainers. He ran past erupting volcanoes. He ran through torrential downpours. He ran in 140° heat. He ran 82 laps around Vatican City, 140 laps around an ambassador’s garden in Jamaica and 335 laps around a parking lot in the Marshall Islands to avoid packs of wild dogs.

Butter, to put it plainly, is a badass. And thus we were keen to sit down with him for “Against the Odds,” a three-part interview series in which we’re profiling individuals who have looked at something that seemed impossible and thought to themselves “Na, I can do it.” You know, for inspiration. And science.

So we recently did just that, chatting with the author and motivational speaker (he’s currently on a multi-city theater tour that looks damn near as grueling as his marathon schedule, and his book, Running The World, is now available for preorder on Amazon) about what drives someone to undertake a challenge like this, what he’s learned from it and the value of a good extension cord.

InsideHook: What was the genesis of the marathon project?

Nick Butter: The inspiration was a guy named Kevin Webber. I met him when I was running the infamous Marathon des Sables race, which is a seven-day race through 280 kilometers of horrendously big sand dunes in the Sahara Desert. Kevin told me that he had terminal prostate cancer and that he had been told he could potentially only live for two more years.

But the thing about this guy is that he was incredibly bubbly, happy, smiley. There was a huge disconnect between the fact that he was telling me he was dying and the fact that his outward expressions as a person were the exact opposite of that. I was like, “What’s going on?”

Then I realized that the whole reason he’s happy is because he understands life. He gets it. He values his time, he appreciates the world and he gets the privilege that we have. For Kevin it was all about just living the best days that he possibly could until his time was up. And it made me realize that it’s actually the same for all of us, we just don’t realize how lucky we are because we are not facing death imminently.

We don’t have that catalytic thing.

Exactly. And Kev said to me, “Don’t wait for a diagnosis. Don’t wait for something in your world to kick you up the backside. Don’t wait for something to go wrong in order for you to make a change and follow your dreams.” I found that to be incredibly powerful. At that point I already thought I was following my dreams because I was running around the world in various races, but I realized I hadn’t been, really. I hadn’t reached my full potential.

A few weeks went by and I wanted to do something that was going to raise money for Prostate Cancer UK, and what better way than to do something that nobody had ever done before, i.e., set a world record? And I realized by Googling it that nobody had ever run a marathon in every country in the world. And so I naively at the time thought, “Well, why not do it?” Little did I know that it would take another two years just to complete the planning phase and get into a position where we could get to the start line.

It seems like the amount of dedication and resilience required to even plan, let alone execute something like this is … not standard. How much of that do you think is innate vs. a learnable, teachable thing?

I don’t think any of it is innate. I think it’s 100% teachable. There’s the whole 10,000 hour rule and you just have to fail a lot of times. Resilience is a compound effect of making lots of mistakes and failing a lot of times and then picking yourself up and carrying on.

Is this what you mean by the concept of “embracing failure” in your talks?

Yeah. I’ve learned that if you are in a position where you fail and you fail and you fail and other people aren’t failing around you, then it looks like you’re not doing as well. But actually, because you’re failing, you’re potentially learning more.

What did those failures look like in terms of this project?

We were in positions where we had visas refused. I was ill, I had attacks and incidents where I was injured, broken bones, and stuff was happening where everything was against us. The amount of times that we got to those positions where we thought we couldn’t do it, there must’ve been 20, 25, 30, 40 … who knows? Hundreds. But I knew that people have done things that are harder in terms of physicality — and not necessarily running, but just anything — and you can get through it. People who’ve been kidnapped or detained as prisoners of war, they’ve gone for days and days without food or water, run across deserts, all sorts of stuff. So the human body has the capability, and as soon as you know that, you can push through it.

Is that a thing you use to push through those moments, to think about people who have had it worse off?

Yeah, definitely. I was running through really horrible cities in the middle of Africa where I was experiencing either some life-threatening behavior or it was too hot, and all the time I’m running past five-year-olds that have nothing but a pair of pants and an empty water bottle and that’s their life. They have no family, no money, no food, no context of the world. And so I felt enormously privileged to even leave my own country to visit somewhere else.

So as soon as you have that context and that perspective of how lucky you are and how physically able you are if your mind will allow it, then of course you use that. Don’t get me wrong, I had times where I just wanted to have a bath or not get up because I was throwing up every five minutes. I can’t tell you the amount of marathons I did with food poisoning or a kidney infection or when I was hit by a car or when I was mugged or when I was shot at or when I was bitten by a dog.

You were mugged?

In Nigeria, in the center of Lagos, I was attacked at knifepoint and gunpoint. And the thing about Lagos market, it’s like a chaotic maze and everything is muddy, dirty, loud, enclosed and really kind of claustrophobic, actually. And so you’re in this environment and then you have people with guns and knives coming at you and you’re kicked to the floor. I had incredibly bruised and cracked ribs via some violent kicking, things were taken away from me. And that was a third of the way through the journey. I still had two thirds of the world to complete. And it wasn’t a city or a country where there was a war on, I still had all the war zones coming up.

Isn’t there then an element of fear that can creep in and undermine your efforts?

I think when the scary stuff has happened — like I had a very close call with a cheetah, or when I was hit by the car, for example — you get shocked, and every human being will have the same reaction to that because that is innate in your body. It’s a human instinct. It’s just how you then deal with it afterwards that’s the important thing.

I think most people in their life have had some form of traffic accident or a collision of some sort, and as soon as you have that accident, afterwards, everybody’s the same. You drive slower, you’re more cautious, you’re thinking about it. And then before long, that fades off and you’re speeding up again and you’re thinking about it less and it disappears. I just try and expedite that process. Sort those fears into the back of my mind quicker. Because this stuff happens, but it doesn’t change the fact that we have to get to the finish line.

So there was a certain amount of, “Oh shit, what have we got ourselves into?” But I look back with a very fond and lucky perspective in that all sorts of other things could have been going on. For example, the coronavirus — had that been happening then with flights being canceled and all that, it may not have been right to carry on, let alone possible. So I was very lucky that those kinds of things didn’t happen.

Embrace the Impossible

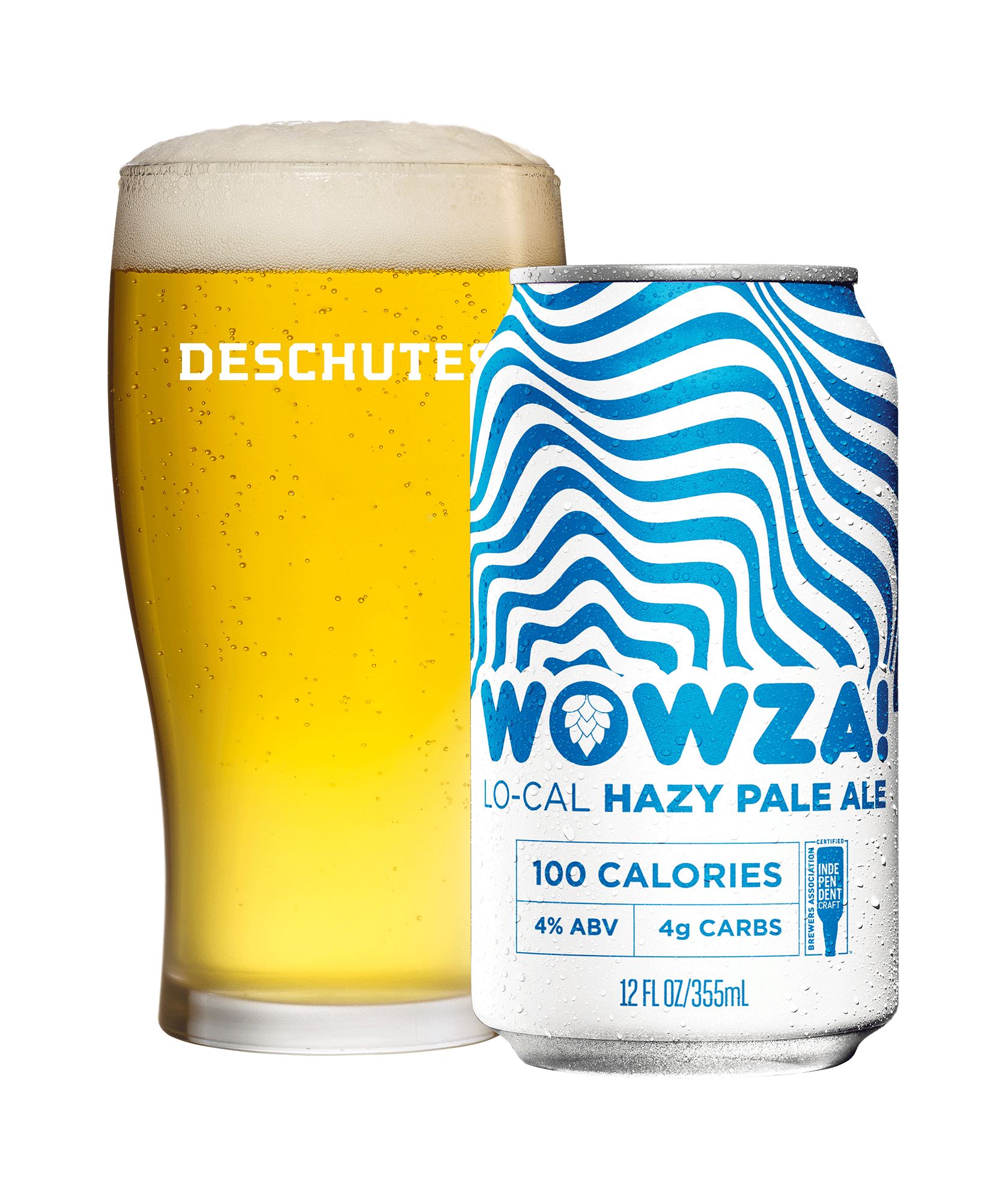

When it comes to accomplishing the truly unlikely, the folks at Deschutes Brewery most certainly know a thing or two. Pioneering the craft beer scene since 1988 through unconventional techniques and a healthy disregard for the brewing mainstream, the Oregon suds mavens have long been creators of brews that nobody saw coming and have taken the beer world by storm.

Such is the case with WOWZA!, their delicious new lo-cal hazy pale ale that clocks in at a mere 100 calories and 4g of carbs. WOWZA! relies on four varieties of hops (Citra, Simcoe, Cashmere and Callista) as well as chicory root to yield big taste without a heavy body, making it an excellent flavor-rich alternative to typical lite beer fare for the discerning tippler.

An accomplishment we’re happy to raise a glass to.

You seem to focus on the benefits that you’ve had rather than the challenges you’ve faced. That’s interesting.

Everybody loves to moan, I think every human being does at some point. But I love to think of the good stuff, and that’s why I’m so busy all the time — I’m always saying ‘Yes’ to things and cramming my day full, because you never know. I’ve had friends and family that have died far too young, and situations happen all the time, be it cancer or a traffic accident. There’s 24 hours in a day, and on average, we live for this magic number of 29,747 days. That’s the amount of days an average British person will live for, and we have the opportunity to do what we want within them.

Do you feel as though being a “yes person” comes back around in a positive way?

Absolutely. It may even come back around to you immediately, but sometimes it does without you even knowing. I suppose it’s a good example on my journey. If I could sum the whole trip up in one word, it would be “people,” because people made stuff happen. By me saying ‘Yes’ to people and agreeing to have a conversation or having dinner with somebody or running with somebody, that led to other conversations and that led to other seemingly endless and completely exponential opportunities. It’s definitely the way forward.

Speaking of moving forward, do you have an internal monologue when you run?

Sometimes I talk to myself or sing to myself out loud if I’m particularly hot or if I’m ill and I need that motivation. But a big chunk of the time my head is somewhere completely different and running is my kind of transport. When you’re driving a car, you don’t think about the fact that you’re driving a car, you just do it and your mind is elsewhere. On a majority of the runs, I wasn’t really thinking about the running. I was thinking about where I was, taking in the culture, that kind of thing.

And you took copious photographs as well. Are there any that conjure really great memories for you?

I took this photo with the sunrise overlooking the tin shacks in La Paz, Bolivia. I was literally there for half a day before flying all the way to North Korea. I just remember looking back at that photo, and the difference between North Korea and home and Bolivia was so big that it kind of struck me with how the diversity of the planet was greater than I could ever imagine.

Has writing your book helped you to view the experience in a new way?

You know what? It probably sounds silly to say this, but writing the book and looking back through everything, it reminds me of how much running there was [laughs]. Because I was taking it one run at a time, one marathon, one flight, one day at a time. Small bite-sized chunks. And then looking back at everything, I think, “Wow, that was actually quite intense.”

What other lessons carried over from your trip into your work as a motivational speaker?

One thing I start with is how I was on my own for the whole trip. I was running on my own, I was flying around the world on my own, I had to make decisions on my own. A lot of people that are struggling with their mental health are in their own head, and I was well and truly in my own head for two years.

But what a lot of people don’t realize day-to-day and I sometimes didn’t realize on my trip is that I had people with me, even though they weren’t by my side — family, friends, my brother, my parents. People all over the world volunteering their time and also random strangers that were coming out to help me all over the world. I had no idea why they were doing it, but they wanted to help.

And it’s exactly the same in normal life, where people are struggling with a stressful time at work or a breakup or anything like that. There are people out there that you don’t know who are able to help you. Like I mentioned earlier, the one word I would sum it up with is “people.” Use the people that are around you. The human species is a very, very special kind of being.

Last question, slightly more tactical: What piece of gear did you find to be most invaluable on your journey?

I think it would be an extension cable, which is probably quite a boring answer [laughs]. But sometimes I’m staying in places that only have one dodgy connection, or maybe I’m sitting in a cafe and the only connection is halfway across the room. An extension cable with the right adapters is everything that I need.

All photography courtesy of Nick Butter

Check out the rest of the “Against the Odds” series:

Thanks for reading InsideHook.

Sign up for our daily newsletter to get more stories just like this.