In 2006, an 11-year-old Victoria Arlen was diagnosed with not one, but two incredibly rare medical conditions known as transverse myelitis and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. She slowly began to lose control of her body, eventually slipping into a vegetative state in which she was completely aware of what was going on around her, but unable to move or communicate.

She remained there for four years.

In 2010, defying the prognosis of countless doctors, she began a miraculous recovery, re-learning to speak, eat and move from scratch. Just two years later, without the use of her legs, she won a gold medal (and three silver) in swimming at the 2012 Paralympic Games in London, setting a new world record in the process.

Still not satisfied, Arlen then dedicated herself to learning to walk again, something experts had told her over and over would never happen. Once again she shattered expectations, not only learning to put one foot in front of the other, but eventually competing (and reaching the semi-finals) on Season 25 of Dancing With the Stars.

Arlen, to put it plainly, is a badass. And thus we were keen to sit down with her for “Against the Odds,” a three-part interview series in which we’re profiling individuals who have looked at something that seemed impossible and thought to themselves “Na, I can do it.” You know, for inspiration. And science.

So we recently did just that, chatting with the ESPN host, 30 For 30 subject, author and motivational speaker about overcoming the odds, the idea of “small victories” and the power of a really good mantra.

InsideHook: So walk us back to the beginning of your recovery in 2010. That seems like an unbelievably daunting road to be looking down.

Victoria Arlen: So against all odds I had started making this “comeback into life,” if you will, but the problem was that for four years, I was pretty much completely immobilized. I had to start from ground zero and build from there. Around the clock speech, occupational and physical therapy, as well as my family and friends stepping up and helping me adjust to this new normal. I had come back from this crazy ordeal, but no one really knew the extent of the damage that had been done, what kind of mental capacity I would be at, what physical capacity I would be able to reach. There were a lot of unknowns in 2010, and so I think my family and I were like, “Okay, we just need to take it day by day, and try to just put one foot in front of the other.”

Do you feel as though you learned a lesson in patience during that time?

I’d like to say yes [laughs]. I still consider myself a pretty impatient person, but I think I did, yeah. I think for me, patience is learning the power of small victories. I was really frustrated because I wanted to be back. I had spent four years watching the world go on without me, and so when there was a remote ability to get back, I just wanted to go for it.

It was my parents and my brothers who really helped me. My mom said it wasn’t just day by day, sometimes it was moment by moment. We all want these massive victories, but it’s the small victories and blinks of hope that really have the brightest and the biggest effect. It was really important to focus on those moments, like celebrating the day I was able to hold my head up for longer than 10, 20, 30 minutes, or being able to sit up on my own. I think we all are brought up to celebrate the big things, but I learned to really celebrate every little thing and be excited about the continual progress, not the fact that I wasn’t where I wanted to be yet.

Can you give an example of a small victory that was particularly memorable?

Even just blinking. That was the catalyst of me letting my family know that I was in there. I started blinking, and I communicated via blinking for almost four months. For anyone else, they would say, “Oh, well, it’s just blinking.” For my family, they were like, “Yeah, but she’s there. She’s communicating.” I remember my mom being like, “Victoria, if nothing else comes back, if this is how we communicate, we’ll make it work. We’re happy with that.” Obviously you want more than that, but I was so grateful just for that teeny, tiny ability that I did have.

Where do you think your tendency to view the world this way comes from?

I really hit the jackpot when it comes to my family. My brothers and I were always brought up that when the going gets tough, the tough get going, but also to really shoot for the stars, to believe in the impossible. My parents were both self-made. My dad was brought up in poverty, and was the first person in his family to go to college. He changed his trajectory. Both my parents shifted their trajectory and created something together. When I was five years old, I told my mom I was going to be an Olympian and win a gold medal. She was like, “Okay, if you work hard, then you know we’re going to support you.”

I was cognitively not communicating with people for four years, but in those four years I paid attention. I paid attention to my parents, my brothers, how they were just continuing to fight for me and believe in me, and so I couldn’t help but follow suit.

I think you are who you surround yourself with. The people that I’ve surrounded myself with really motivate me and inspire me, and that’s what they did in those four years. When they had every reason to not be positive, when they had every reason to not have hope, they did. I think that’s really what gave me the strength, but also taught me so much about fighting — just paying attention to my family.

Do you even believe in the idea of “disadvantage,” or do you think it’s all a matter of perspective?

It’s for sure a matter of perspective. I think you are the writer of that. You are the person that defines that, not anyone else.

I think for me, a turning point was actually when I was about three and a half years into this vegetative state, and I was like, “Oh, my God, this is insane. I don’t want to do this anymore.” I knew if I continued to give in to these negative thoughts, if I continued to give in to what was being said around me with every odd that doctors were giving and the unknown of whether or not I was going to wake up tomorrow … I needed something to shift my perspective.

I started to focus on the things I did have to be grateful for, starting with the mere fact that I had complete and clear brain capacity, when according to everyone else, I shouldn’t. Building this list of gratitude from literally rock bottom really shifted my perspective. Which then created a lot of hope that maybe things could get better, that maybe I could be that one in a billion that makes it through.

That hope for what I would be able to do as opposed to negativity toward what I couldn’t do in the current moment was huge for me. I think perspective is everything. I think it’s easy to lose it. I still lose it from time to time, especially with all the craziness going on right now. Because doom and gloom is easy, but having hope and believing in the impossible is where the work comes in. It’s obviously a hard time to do that right now, but when you really dig your heels in and do it, it can make a world of difference. It can literally turn something impossible into possible.

Embrace the Impossible

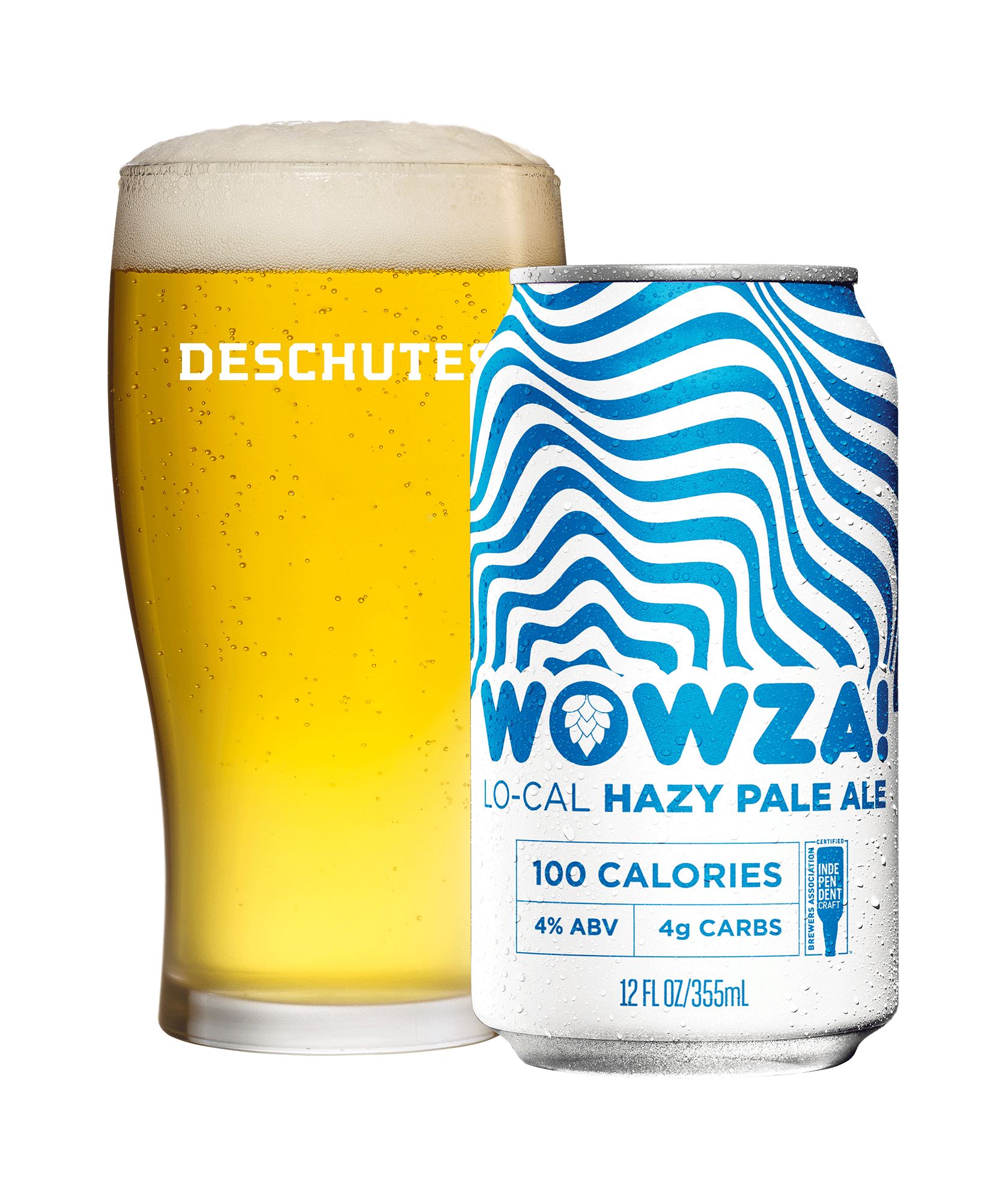

When it comes to accomplishing the truly unlikely, the folks at Deschutes Brewery most certainly know a thing or two. Pioneering the craft beer scene since 1988 through unconventional techniques and a healthy disregard for the brewing mainstream, the Oregon suds mavens have long been creators of brews that nobody saw coming and have taken the beer world by storm.

Such is the case with WOWZA!, their delicious new lo-cal hazy pale ale that clocks in at a mere 100 calories and 4g of carbs. WOWZA! relies on four varieties of hops (Citra, Simcoe, Cashmere and Callista) as well as chicory root to yield big taste without a heavy body, making it an excellent flavor-rich alternative to typical lite beer fare for the discerning tippler.

An accomplishment we’re happy to raise a glass to.

Did you have any kind of mantra to help you get through difficult moments?

“Face it, embrace it, defy it and conquer it” was a mantra that I came up with in my vegetative state, and is actually in the foundation of most of my speaking tours. I knew I needed something to say to myself, and that saying “you can do it” or “I will get better” wasn’t anything special. I knew I needed something with a little more color.

You had to personalize it.

Yeah, I had to make it something mine, my vibe.

Can you break it down?

So you’ve got this situation, you obviously need to face it. By burying it underneath the carpet, it’s going to come back and bite you in the butt 10 times more than it originally would have. Then you have to embrace it, and I think that’s probably one of the hardest things to do — to embrace your situation, embrace the very place that you are.

Then by doing so, you’re able to really start shifting your way toward defying what’s up against you, ultimately allowing you to conquer it. It’s a four-step breakdown of how to overcome adversity, and that was something that really helped me throughout all of it. I think sometimes when you break things down, when you break challenges or impossible odds down into steps, they’re not as scary as one big, giant thing.

I’ve also seen you say “accept the diagnosis, not the prognosis” — can you speak further to that?

That was actually something my mom started saying when we had doctor after doctor, expert after expert saying, “She’s not going to make it,” and then I would make it. They’re like, “Well, she’s going to be in a vegetative state the rest of her life,” or, “The Victoria you once knew is not coming back.” They just kept trying to convince my family to give up, and my parents were like, “Look, we understand the diagnosis. We understand the severity of the situation. But you don’t know our daughter.”

Accepting the diagnosis but not the prognosis was a huge turning point for my family. By accepting the diagnosis, obviously you have to be real and be a realist about the situation. But the prognosis, on the other hand, that’s a whole different story, because everyone is different — even when I was learning how to walk again, and all these other things I was able to do. You can accept the diagnosis, but the prognosis is yours to write.

Aside from your family, who else has been instrumental in your journey?

I had really wanted to try to make it to London, and I was a year out from the games (Ed. note: the 2012 Summer Paralympics in London). I had coaches laughing at me, people saying, “You’re never going to make it.” When I found John, my coach, we were about six months out from the games, three months out from trials. I went in so nervously because I had been shot down by so many other people. He was the last person I went to, and I was like, “Oh, here we go.” He says to me, “What are your goals?” I was like, “My goal, I just want to make the team.” He just looked back at me and he goes, “Well, if I’m going to coach you, the goal isn’t just to make the team. The goal is to win a gold medal. If that’s not your goal, then I can’t coach you.” I just looked at him and I was thinking, “Really?”

He says to me, “If you do what I say, if you show up, I will show up, and that’s gonna be our goal.” He was by far the toughest coach on the face of the planet, but someone he also pushed me beyond. In a month’s time, I broke my first world record, and this is the first thing he said to me: “You could have gone faster.”

I’m like, “No one in the world went faster than that.” He goes, “I’m not talking about the world. I’m talking about you and I, and what I know you’re capable of doing.” That was a shifting point for me, and reminded me that sometimes our dreams and our goals, we cut ourselves short. John was someone who taught me “Don’t just try to make the team. Try to go win a gold medal.” Metaphorically speaking. Unless you actually want to win a gold medal [laughs].

Ok last question: if there was one thing that you wanted people to take away from your story, especially in trying times like these, what would it be?

I would say that the toughest climbs have the prettiest views. I think we get so caught up in those tough climbs, those challenges, that we forget that there’s a really beautiful view waiting for you at the top. You just have to keep climbing, and it’s OK to fall down, and it’s OK to stumble along the way, but just keep climbing. Just keep putting one foot in front of the other.

All images courtesy of Victoria Arlen

Check out the rest of the “Against the Odds” series:

Thanks for reading InsideHook.

Sign up for our daily newsletter to get more stories just like this.