Michael Jordan is, arguably, the progenitor of the modern basketball aesthetic. To watch a basketball game today is to vicariously rifle through his canon of style choices.

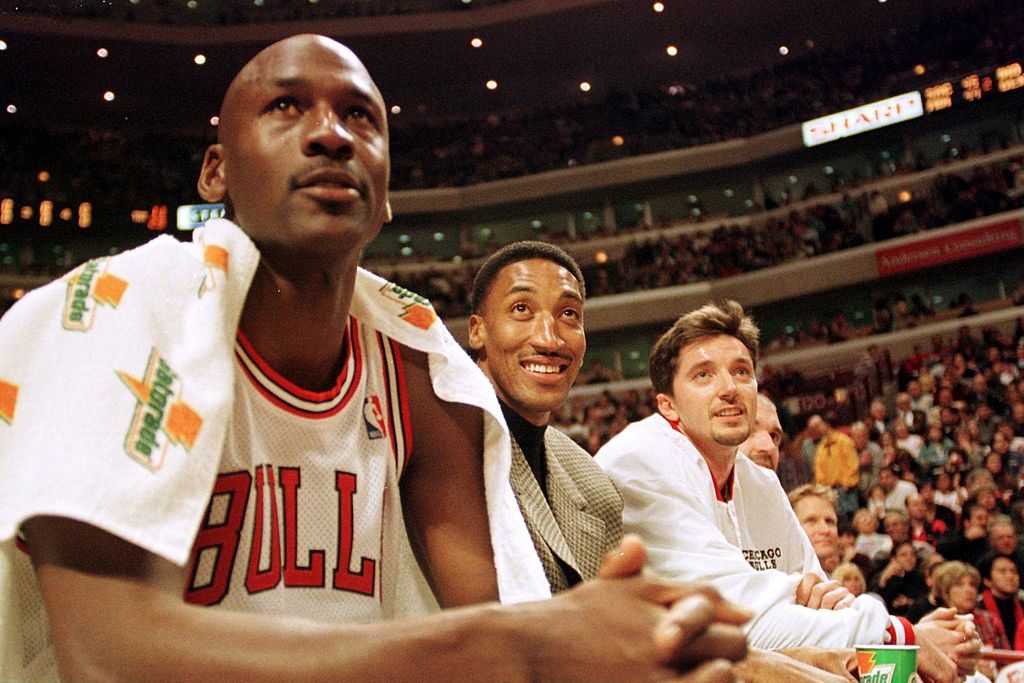

In the 1990s, before intra-squad scarf beef and the scrutiny of League Fits, Jordan famously wore suits to postgame press conferences, making him a precursor to the wave of haute fashion-cum-streetwear that has swept today’s NBA. His ritual of wearing UNC practice shorts under his Bulls uniform (thereby necessitating baggier bottoms to conceal them) eventually encouraged the whole league to abandon short shorts. Most notably, his partnership with Nike birthed a new breed of sneakers engineered with aeronautic precision and an ever-increasing dose of swagger; arguably, the arrival of the Air Jordans in 1984 — and the subsequent Jordan Brand — is the single most significant basketball-related development since the three-point line was implemented five years earlier.

“His on-court style influenced people’s off-court style,” says Russ Bengtson, a former longtime editor for Complex and Slam magazine. “There wasn’t a runway in the tunnel before the games, but he wore suits anyways. His fashion legacy was the Jordan jersey — it’s the sweatband halfway down his forearm and the baggy shorts and, obviously, the shoes and all the Jordan Brand apparel that came out later.”

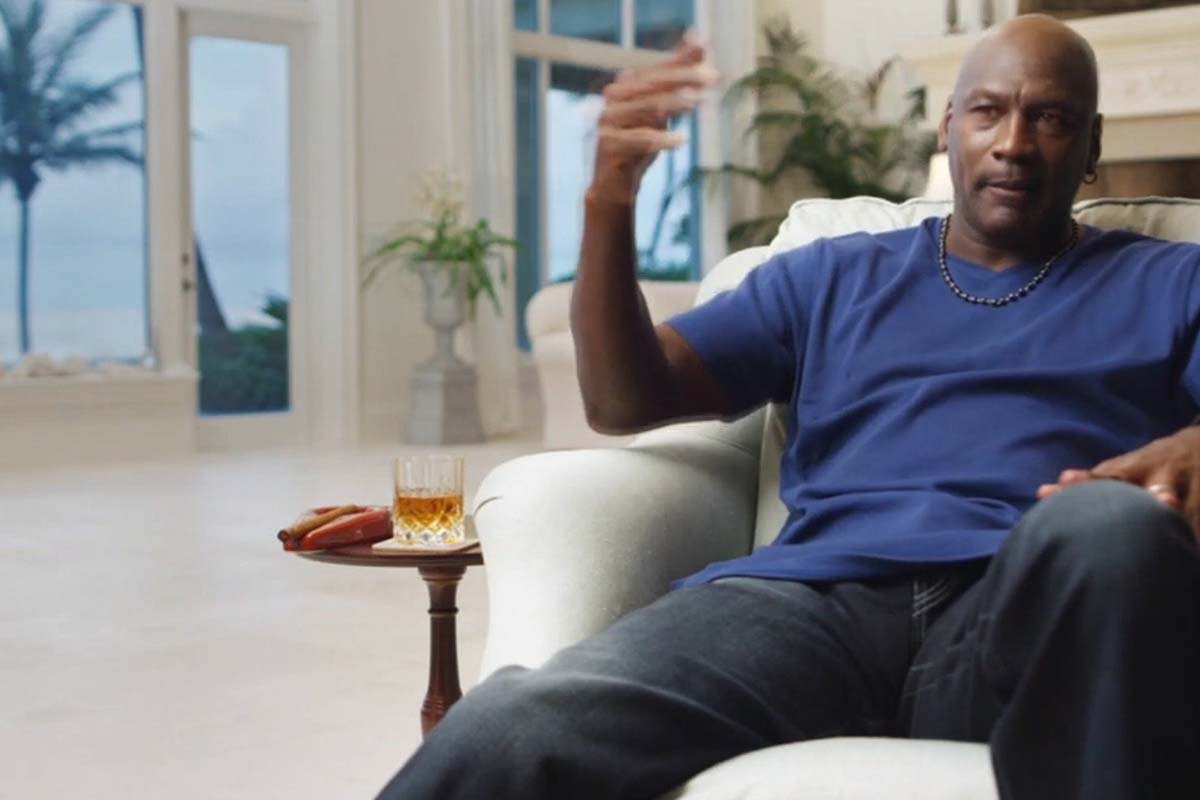

By all appearances, Jordan hasn’t bought new clothes in 30 years. For a megastar with essentially limitless money, he dresses like he’s interviewing to be Sublime’s road manager. He’s been thrown off of golf courses for wearing cargo pants. He threw the ceremonial first pitch of game one of the 1993 ALCS clad in a Canadian Tuxedo. His pants billow like the sails of the great seafaring ships of yore and his blazers reduce a 6’6 miracle of biology into a very convincing Vincent Adultman. Stumbling on the overlong deconstructed hem of his meticulously distressed boot-cut jeans for the better part of this century, Jordan pierced his ear, grew problematic facial hair and became a meme, a relic of culture’s Ugly-Neutral era.

And yet, by disregarding the world of good taste, he carved out his own lane and became the unwitting founder of meta-ironic fashion, his style so tragically unhip that at some point it became unclear whether it should be mocked or applauded or both. The “Jordan Rules,” it seems, applied not only to his game, but also to the particular school of dressing he helped create: one defined not by its adherence to any kind of recognizable formula or objective, but rather by an utter lack of fucks that only money or status can buy.

“The thing I like about Jordan now is that he’s never really changed his stories” says Jeremy Kirkland, the host of Mr. Porter Live and the style interview podcast Blamo! “To this day, it’s still big, big jeans with paint splatters and weird frays, paired with a massive oversize jacket, an earring and an all-gold Rolex.”

Of course, because time is a flat circle, today’s fashion landscape is defined by attempts to reappropriate the ostensibly (and ostentatiously) unfashionable and reimagine it into something desirable. The ultimate cool-kid flex is to intentionally eschew the trappings of cool-kid-dom: anybody can look good in Levi 511s, the real test is pulling off boxy, high-waisted work pants, or gaudy windbreakers with a pair of geriatric velcro sneakers. Look at Balenciaga’s clunky Triple S Runners, which set off a wave of similarly unwieldy shoes in 2017 that have clomped through Soho for the last three years without cease. Yeezy 500s, resembling a bulbous ripening gourd, dropped at the beginning of 2018; A$AP Rocky debuted his first signature shoe for Under Armour in December 2018, borrowing heavily from the silhouette of the Osiris D3 skate shoe. Last spring, Vetements released collaborations with Oakley and Reebok, turning neon wraparound visors and “inflatable” sneakers into capital-f Fashion.

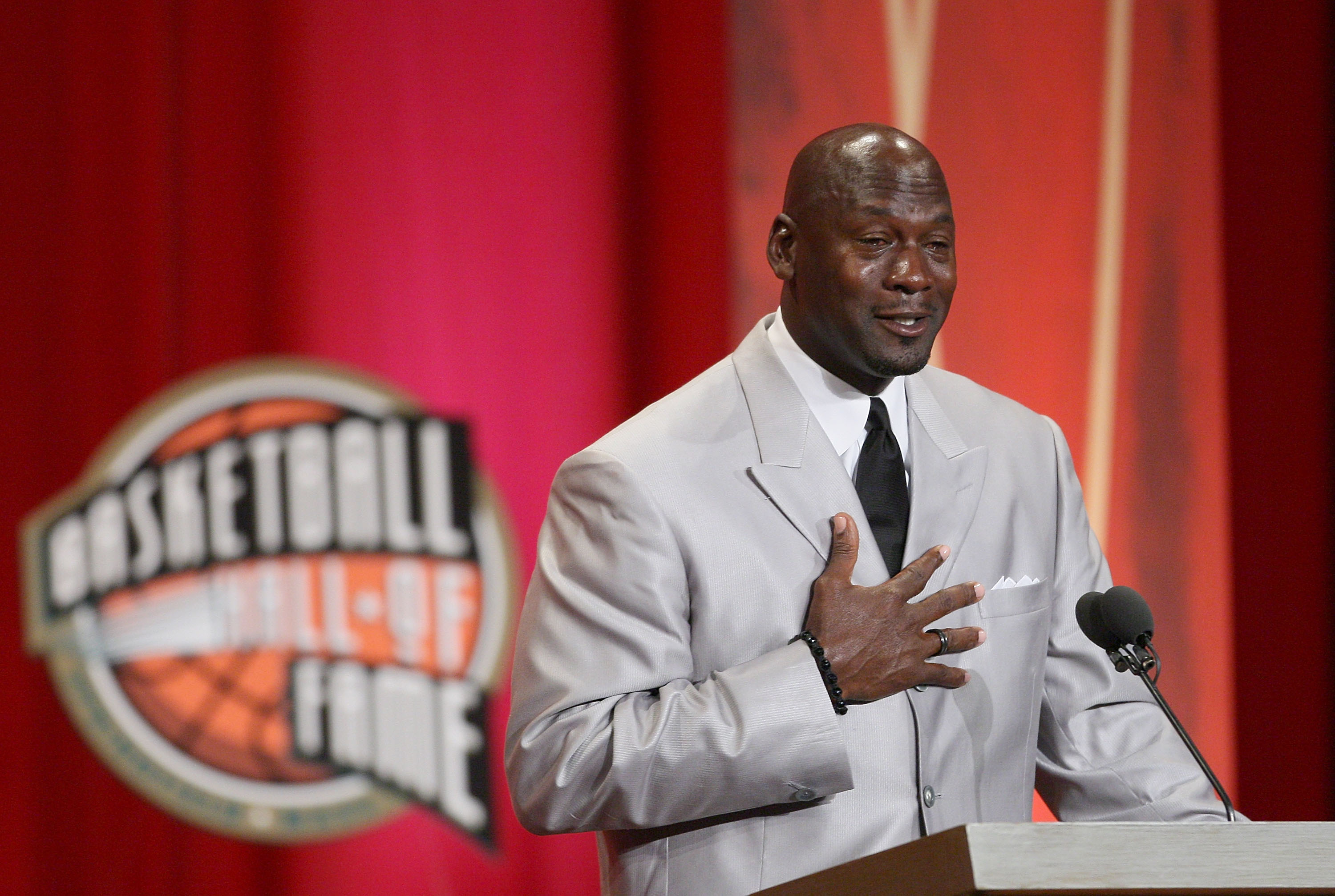

So, as the world at large backslides into the past, Michael Jordan has fittingly found his way back in the sartorial spotlight. During the leadup to The Last Dance, ESPN’s 10-part documentary series about Jordan’s final season in Chicago, Jordan’s style has been revisited, even celebrated: High Snobiety hailed MJ as “the GOAT of IDGAF style”; Parisian vintage dealer Gauthier Borsarello declared Michael Jordan his double fitspo on Instagram, (fitspo meaning “fit inspiration,” a person who motivates you to either get fit or get a fit off). While The Last Dance may largely reveal the turmoil at the end of a proud, miserable dynasty, Jordan and his massive clothes have been engaged in the infinitely more revealing and important debate of whether clothes make the man, or vice versa.

Still, Jordan’s relationship with fashion is difficult to parse because of his overwhelming Jordan-ness, which simultaneously amplified and muted the conversation. Jordan’s on-court production and cultural significance are so overwhelming that they tend to supersede everything else. Who are we, mere mortals, to question the sartorial whims of the gods?

“Jordan was already an icon long before people noticed his off-court-outfits were pretty suspect,” notes Bengtson. “By the time people realized the extent of the baggy jeans and huge shirts, the consensus was basically ‘Ok, he’s Mike, he can wear what he wants.’”

Similarly, Jordan was the first athlete to understand the power of his brand — he was the face that launched a thousand sponsorships. The guy was an inescapable phenomenon, but he was hardly knowable; his most famous quote — “Republicans buy sneakers, too”— was pure evasion, pardoning him from the responsibility of having an opinion. His on-court persona was Thanos-ian, the specter of inevitable defeat looming over his opponents, but as a pitchman he played the charismatic, friendly cipher. “The image of Jordan during the early years with the Bulls was as contrived as any character in fiction,” says Bengtson. “So when we got any glimpses of his actual personality, there was always a jolt of ‘Oh, this is who he is?’”

This inscrutability only added to Jordan’s allure. As a result, his every movement and outfit was catalogued and pored over by legions of adoring fans who hoped that any detail that might offer some foothold into Jordan’s inner life; the mere fact that it’s common knowledge Jordan dresses like a McMansion who wishes it were a real boy implies that Jordan’s style generated considerable attention. “Even within the special context of the Dream Team,” Kirkland remembers, “People really idealized and fantasized about everything Michael Jordan did and everything he wore. Charles Barkley, for example, dressed very similarly, but people don’t have that awareness of him.”

Despite the continued fascination with his on- and off-court style, Jordan seemed as unconcerned about this particular arena as he was about Rodney McCray’s mental health. “Jordan didn’t really care too much about clothes,” Kirkland remarks. “He gambled, he golfed, and he had a serious anger issue, and was one of the greatest athletes of all time. Fashion-wise, his style is very much I don’t give a fuck.”

More precisely, Jordan’s visual constancy through the ages suggests that he cares for the actual clothes themselves, but not for the pretensions of fashion. “MJ’s clothes are almost the ultimate expression of dad style,” says Bengtson. “You might not dress like your dad, but he’s still your dad. You wouldn’t wear what he does, but he’s settled into what he likes and there’s not much you can do.”

For the most part, fashion is the last remaining vagary left in the general conception of Jordan. The basketball part is unimpeachable — at the absolute worst, he’s the second best player of all time. So solid is his legacy that even his personal failings — the man was, like, super mean — have calcified into the backbone of his hagiography. But whereas Michael Jordan hasn’t suited up for an NBA game in 17 years, he’s continued to put on clothes and go into public (until, well, you know), gradually drifting away from the zeitgeist that he inadvertently created, before recently watching it orbit back to him.

“When Jordan was coming up,” Kirkland notes, “there weren’t that many cool guys tailoring yet. It was all Armani — big suits, huge shoulder pads, tons of structure, very low buttoning points and high-waisted pants. Right now, if you took out Jordan and just photoshopped Harry Styles’s head into that look, someone is going to say it’s a new Gucci collection.”

Although Jordan has been firmly entrenched as a seminal figure in the fashion world for decades, he has always kept it at an odd distance. Interestingly, he cemented his place in the industry not because of a wellspring of artistic talent or a discerning eye or even an overflow of enthusiasm for the subject, but rather because his sheer hoops talent and his partnership with Tinker Hatfield, the legendary Nike designer, catapulted Jordan to the upper strata of fame after the Air Jordans hit retailers before the start of his second season. Unlike modern stars like Russell Westbrook or D’Angelo Russell who have immersed themselves in the field, Jordan didn’t reciprocate the love.

“I look at Mike’s relationship with clothes the same I look at his with music.” Bengtson says. “He was the hero of a hip-hop generation, but he never listened to hip hop; he listened to Anita Baker. He was an easy-listening kind of guy, who would just come out and murder you. And I think with clothes it’s the same way: Air Jordan is really his fashion legacy, even if 40-year-old Mike came out afterwards in baggy, artfully ripped jeans, a big shirt and a big sport coat.”

As much as this legacy is based on Jordan’s athletic accomplishments, it is at least equally reliant on his innate coolness, which slowly diminishes each year. In his 20s and 30s, Jordan was an iconoclast, redrawing the sport’s visual vocabulary. Now a 57-year-old multi-billionaire, Jordan has become a member of the stolid establishment he once rearranged. It’s tempting to look at present-day Michael Jordan, dressed like every single one of his shirts is a sleep shirt that his mom promises he’ll grow into, and project that his commitment to ‘90s-era style is a desperate, vain attempt to keep his glory days within sight. If people struggle to move on from their high school letterman jackets, it’s doubly understandable if Michael Jordan feels the most vital when he occupies that homey little sliver of overlap on the Venn Diagram of Hot Topic and Josef A. Bank.

Really, though, Jordan’s wardrobe stems from total freedom, not melancholy; it is proof that Jordan, like Adam Sandler, has chosen comfort over clout. He wears his weird anachronistic clothes — shirts with sleeves beyond his fingertips, pants speckled with paint — simply because he likes them. And isn’t that the whole point?

If clothing implicitly sends a message — I’m rich, I’m cool, I’m quirky, I’m With Stupid — then Jordan broadcasts utter contentment, impervious to puny little tweets telling him that he’s dressed like Taylor Hicks. For Jordan, his stylistic inertia isn’t death, but rather proof of his purchase.

“The thing that Jordan had more than anybody was obscene confidence — insane, obnoxious confidence” says Kirkland. “If you have that, in any piece of clothing you put on, you’ll always seem like the coolest motherfucker ever.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.