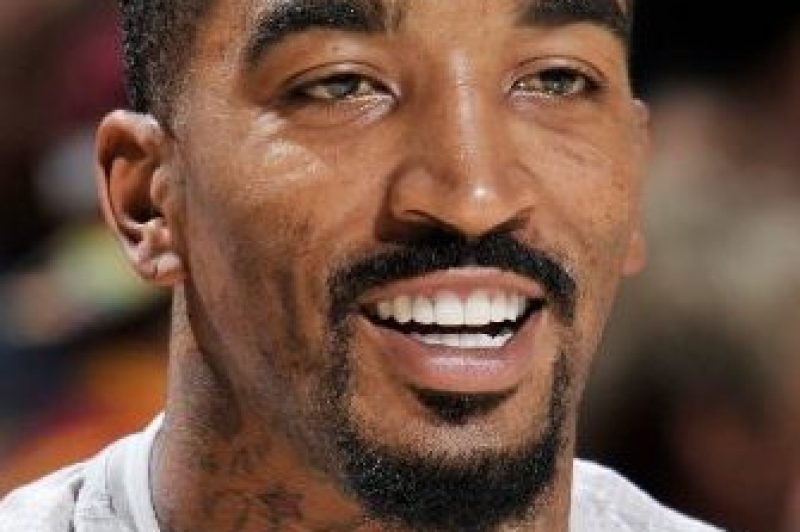

Cleveland Cavaliers shooting guard J.R. Smith is, by all accounts, a character. But in a recent New Yorker profile, the NBA star argued that he was actually just misunderstood, his oddball actions misrepresented by the league.

Smith is as well known for his eccentric behavior as he is his hustle and dramatic three-pointers. But he’s also made headlines for his out-of-left-field behavior on the court. Case in point: In 2014, he untied Dallas Mavericks star Shawn Marion’s shoe during a game, and tried to do the same to Piston Greg Monroe, which cost him a $50,000 league fine. He’s also been involved in on-court fights, numerous traffic incidents, has had a few drug violations, and made a couple of serious Twitter gaffes (he posted a salacious photo of Tahiry Jose in one instance; and in another, tweeted “Celebrate the deaths of the people in 9/11!” on the anniversary).

At first glance, Smith sounds like a practical joker, who has little self-control. But Smith, who grew up a bullied child in Millstone, New Jersey, insists that people just don’t get him.

“I can’t say what I want and how I want,” he told The New Yorker. “Because it’s me. When I try to explain myself or express myself, it seems to come off the wrong way.”

Sometimes, he feels these misunderstandings are deliberate. “I tried to have fun on the court, pulling somebody’s shoestring: fifty-thousand-dollar fine,” he said. “I’d been doing that for years.”

He also mentioned that his friend and fellow NBA star Dwight Howard

“… was untying laces for four or five years, but nobody said anything! They’re just like, ‘Look how much Dwight enjoys the game!’ Then I do it, and the same people are like, ‘Look at J.R.: he doesn’t take the game seriously.’ Why is it that Dwight loves the game and I don’t? Why can’t I have that much fun playing?”

Smith feels some of the controversy surrounding his behavior is inversely related to the superstar treatment he receives as a successful athlete. “Nobody treated me that way, until I got to the NBA,” he said. “To this day, probably one reason they call me a knucklehead is that I can’t understand: Why can’t you treat everybody the same?”

But for all of Smith’s frustration about how he’s perceived, his supportive family, including his two children, give him some peace of mind. “I’ve got my family, who’ve been my friends my whole life,” he said, when asked about them. “They know where my heart is.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.