Novak Djokovic has seen better days. Pro tennis is suspended and the No. 1 men’s player has used newfound free time to air out some of his dumbest and most dangerous opinions. Most importantly: he is “opposed to vaccination,” and positive emotions can clarify polluted water. A pandemic is maybe not the ideal time to question conventional science and public health on a massive public platform, but Novak has always been fond of, um, alternative ways of seeing the world. With the sports-news cycle dedicated almost entirely to “shit athletes say in webcam interviews,” his views are finally on full display, and it might be the most embarrassing moment of his professional career. (An epidemiologist working with the Serbian government on coronavirus policy, who is a fan, very politely requested that he shut his trap last month.)

In times like these, it helps to have a supportive fan base. A fan base that is intense, interconnected and willing to overlook silly things like “anti-vaxxing” or “allowing frauds to peddle $50 ‘Advanced Brain Nutrients’ to your followers.” And not just overlook them, but endorse them as special, and different. That’s what the Nolefam can do. (“Nole” is a nickname for “Novak” per Serbian convention; “fam” is family, which is of course what you would call any diffuse group of passionate and conspiratorial people online.) They are the fans Novak Djokovic needed, and perhaps they were the fans he was fated to have.

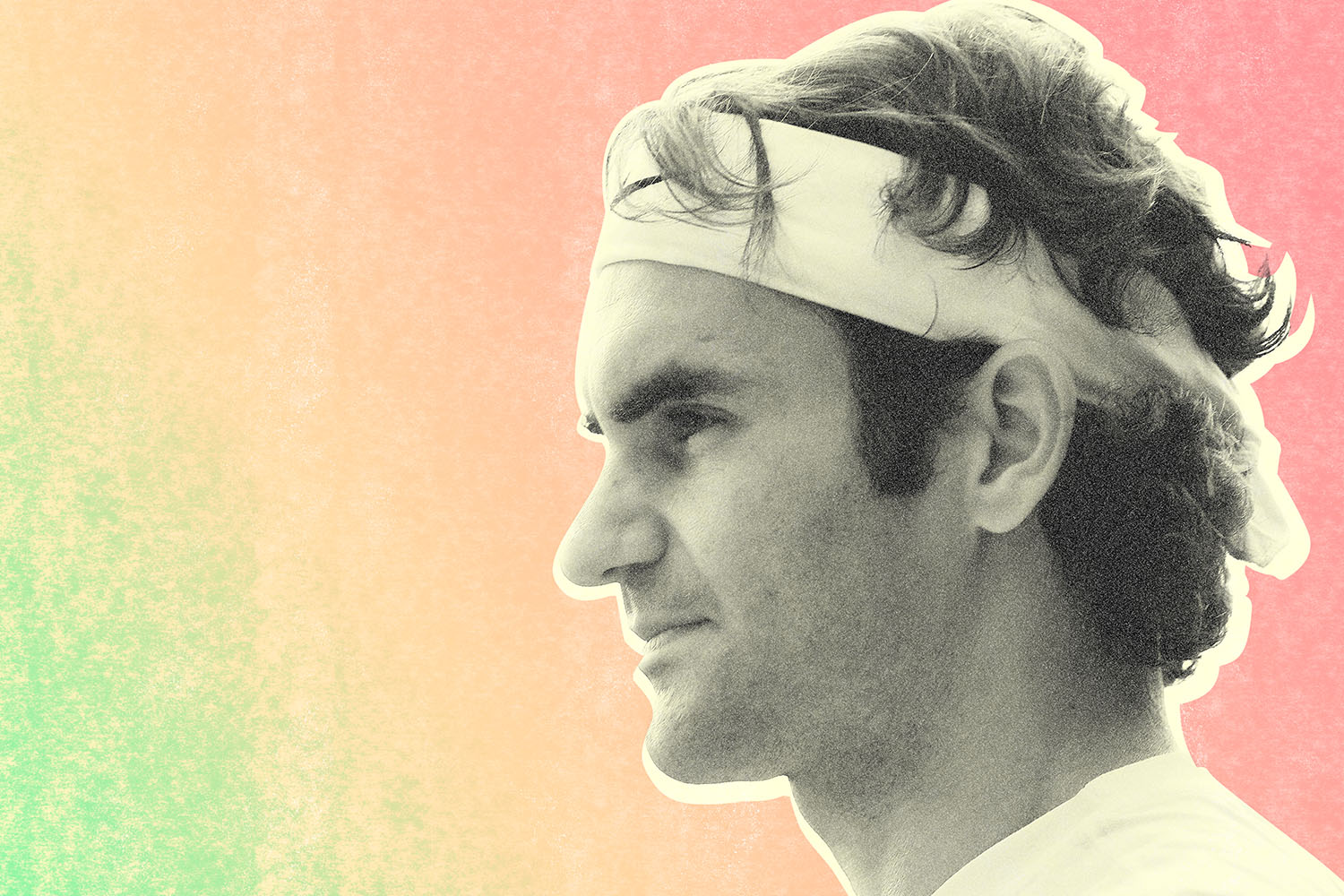

Every athlete’s constituency offers a prism through which to view the athlete themself; it tells you something about the nature of his or her appeal. Roger Federer follower? You probably have a favorite pair of slacks. Rafael Nadal acolyte? You grunt conspicuously at the gym.

Then there’s Djokovic, who — forgive me as I veer into morning-show flatulence for a minute — will likely go down as the greatest of all time, however you wish to take measure of that. You can go with the hard numbers: he’s younger than his peers Rafa and Roger, has had a better run of recent results, and is likely to pass them both up in Grand Slam counts; plus he can point to favorable head-to-head records against each. Or you can take a more subjective measure: at his absolute peak, whether you prefer 2011 or 2015, he was the hardest player to beat who has ever lived. Nobody has ever been better at putting the ball back into play. Nobody has made the idea of hitting a winner look so hopeless for their (often world-historically great) opposition. And nobody has ever managed such absurd shotmaking at the outermost limits of their reach and flexibility.

How is it possible for someone with a realistic GOAT candidacy in their chosen field to suffer an inferiority complex? Maybe it’s the faces in the crowd. Take your pick of armchair explanations as to why — he’s a third wheel in the Rafa-Roger romance, his baseline grind is less aesthetically pleasing than their sweaty or sweatless exertions, he’s never maintained a consistent on-court persona, his boob-throwing victory dance is thirsty and miserable — but general perception is that Djokovic has never quite won the affection of neutral fans like his two internationally adored peers have. I write “perception,” but there are plenty of painfully concrete examples. The 2019 Wimbledon final was just the latest: 15,000 people on Centre Court and nearly each and every strawberry-chomping one of them rooting lustily for Roger Federer. They were exultant when Federer had his two match points in the fifth set, despondent when he lost them, and utterly stupefied when Djokovic won in the tiebreak an hour later. Novak isn’t oblivious to the reality, either; he just warps it to his liking. After the match he described his coping mechanism: “‘I like to transmutate it in a way: When the crowd is chanting ‘Roger’ I hear ‘Novak’. It sounds silly, but it is like that.”

That’s a mature — or at least psychologically sophisticated — Novak talking, not the one who used to do goofy impressions of fellow players or don a fake afro. He doesn’t think the world is out to get him and he sees no dark cabal.

But while the shepherd appears to have found peace with his lot in life, the same can not be said for the sheep. Despite backing one of the most successful athletes in the history of individual sport, his fans often behave as if the world is strategically arrayed against their man’s success. Journalists, of course, are part of that world, and need to be called out when they’re complicit in the treachery which has held their man to — let’s see — a record $143mm in prize winnings, 17 Slams and 34 Masters titles. By the lights of the rabid Djokovic supporter, the press is just another force trying to suppress this man and his feats. All that I will concede: Novak Djokovic doesn’t inspire as much flow-state, embarrassingly purple prose from the commentariat as the other two do. (Guilty as charged.) But “You people don’t write as rhapsodically about my guy as the other two guys” is a pretty lame basis for conspiracy theory.

I have spoken to reporters who have taken more than their share of verbal abuse from every major player’s fan base at one time or another, and they all confirm that the Nolefam has a flavor all its own. “They think their guy is disrespected, and that’s their grievance. And they’re not always wrong. But their paranoia about it — they come up with elaborate theories about conspiracies against him,” said reporter Ben Rothenberg, one of the sport’s major newsbreakers, whether at the New York Times or on Twitter. Rothenberg has been quick to detect and call out the reckless pseudoscience and snake oil that is being peddled on Djokovic’s quarantine live chats. His critiques are on point, and one should be able to see this whether or not one enjoys the way Novak Djokovic plays tennis. But passion clouds judgment, and into Ben’s mentions, the deluge commences. You can trudge through the muck to see it for yourself.

Simon Briggs, tennis correspondent at The Telegraph, agreed with the conspiratorial nature of the Nolefam, and also pointed out their remarkable organizational capacity. “There is a sense of coordination among Novak fans which doesn’t seem to happen with the others. You still get the same vehemence, but there’s a slight sense that they … it’s exponential on your notifications because they all like each other’s posts all the time, right? So they kind of just redouble, and redouble.” Briggs, who often writes about the backroom politics of the tour, doesn’t mind having his work challenged, but he does take issue with the notion that he and his critics are on equal footing with respect to information. “What I write is quite closely briefed,” Briggs said. “This kind of idea that I’ve made it all up or that I’ve missed the kind of big picture because I’ve challenged some of their prejudices is quite amusing.”

He has found himself at the center of some confounding conspiracies as well. Once, he chose to reply to some criticism, which he regretted. “It was just like kicking a wasp’s nest. It was absolutely amazing. And I was just like, ‘What an idiot I am.’” It’s not the only zoological metaphor that has taken hold. In some corners of of the tennis internet, “Molefarm” has emerged as a handy derogation for the Nolefam.

Now, with Djokovic doing things that can actually materially harm people’s health and scam them out of their money, not all his fans can continue to defend his actions. As with any form of religious fervor, it’s unfair to stain the moderates with the sins of the radical fringe. Plenty of members of the Nolefam feel that this latest indiscretion is something they simply can’t stomach.

The man himself, though, seems unbowed. After taking heat for hosting a snake-oil salesman on his livestream with hundreds of thousands of viewers, he invited his buddy back the very next week. A slap on the wrist from the lamestream media? No matter. A true believer can’t be silenced — and, by the same token, neither can his true believers, either.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.