Less than a month after airing the final episodes of The Last Dance, ESPN is offering up another nostalgic look back at 1998, this time shifting its focus to the historic home-run race that year between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa with Long Gone Summer.

The latest edition of the network’s 30 for 30 documentary series made its debut on Sunday, reminding us of the unbridled joy that accompanied watching two division rivals — one a soft-spoken guy from California with forearms like cinder blocks, the other a flashy charmer from the Dominican Republic with a signature home run hop — go head to head. Of course, much of the magic of that season has faded now that we know both players were likely taking steroids. (McGwire has admitted to his steroid use, while Sosa has repeatedly denied it, despite a New York Times report claiming he tested positive.) Director A.J. Schnack was thus presented with a challenge: How do you recapture the glee of that season while also acknowledging the dark cloud that now hangs over it?

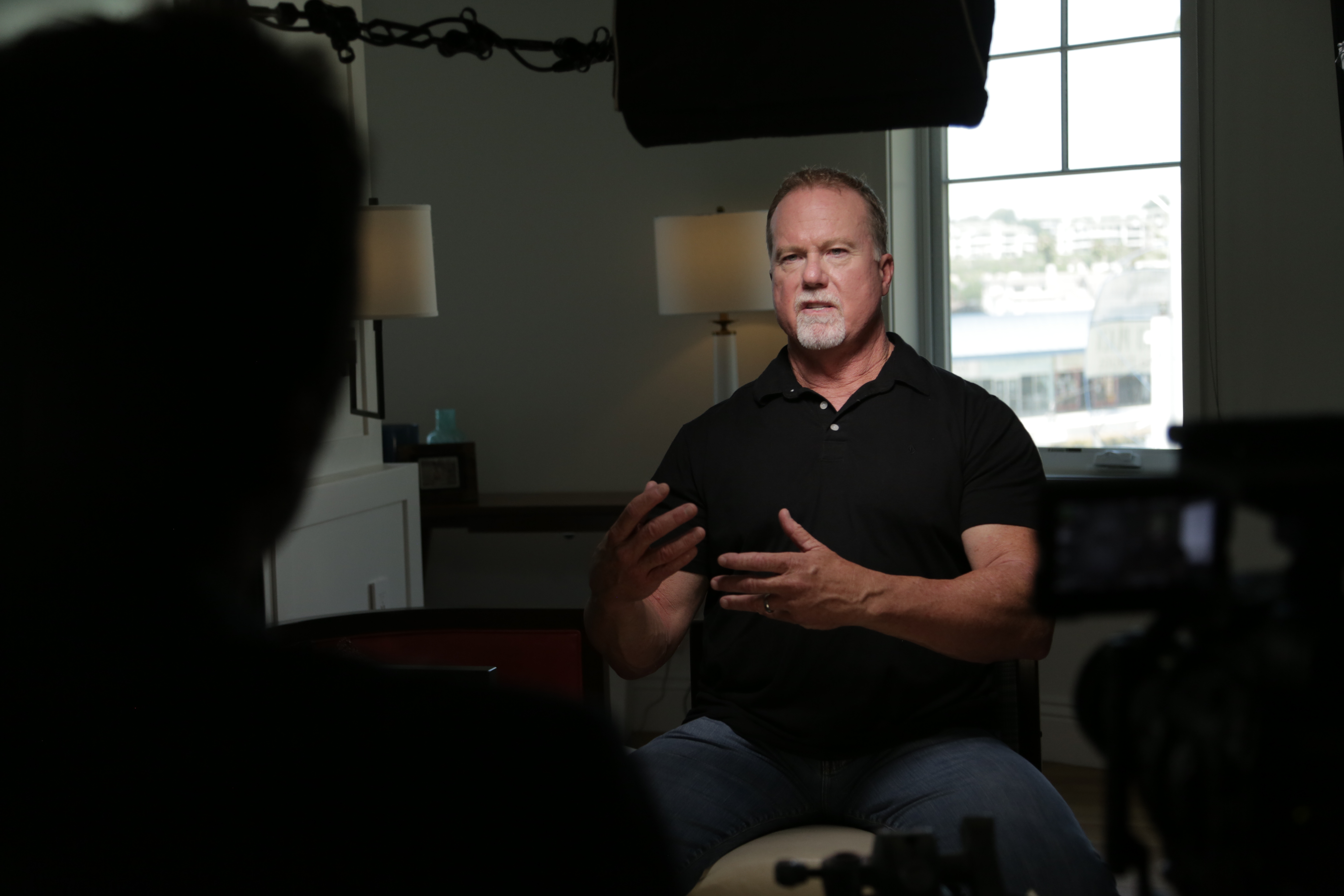

We caught up with Schnack to find out the answer to that and other burning questions — including Sosa’s hesitations about participating, how he landed Jeff Tweedy for the score and how COVID-19 forced some last-minute edits.

InsideHook: Tell me a little about the process of getting Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa to agree to participate in the doc. Did they take a lot of convincing?

A.J. Schnack: Well, I started talking with ESPN back in 2017 about trying to make a film around this subject, and pretty famously neither Mark or Sammy do a lot of longform interviews. So, that was kind of the challenge from the beginning: Can you get to these guys? Can you get them to want to participate? It was certainly a process. I met with both of them in advance. I went down to Miami to visit with Sammy, and I live in Southern California, so I was able to meet up with Mark a couple of times and talked to him on the phone a bunch more. Just over time, telling them kind of the film I wanted to make and how I wanted to tell this story. I think because I grew up outside of St. Louis, was a Cardinal fan, have the Cardinals-Cubs rivalry in my family, I think the personal connection sort of to the teams and to the story was one of the reasons why they agreed to do it.

Obviously that Cubs-Cardinals rivalry was such a huge part of the appeal of that home run race. How do you think it would have played out if it was Ken Griffey, Jr., chasing McGwire instead of Sosa?

[The rivalry] was huge, because Sammy just became this … he was such a contrast to Mark. Mark was just kind of a put-your-head-down, keep-going-forward kind of guy, which is true to him I think still today. Whereas Sammy was like, “Wait, all the sunshine is on me. Great. Fantastic. Okay. I’m happy to talk to everybody and show you how excited and happy I am.” So, I think the contrast between those two things, first of all, was important, whether or not it was part of this huge and ongoing and historic rivalry between two original franchises. But it’s what most of our memories of that race are all about that game at Busch Stadium, where Mark hits number 62, and Sammy runs in from the outfield and they embraced. The Mariners aren’t going to come to Busch Stadium in September. So, yeah, I think it was key. I think there’s certainly still would have been interest, but I don’t know that it would have been the national phenomenon that it turned out to be.

What surprised you most over the course of putting this film together?

You take on something like this, you try to read everything you can that people have said in the past. So one of the things that was gratifying immediately was going into interviews and hearing new stuff from people. They weren’t just telling the same story that they had always told. With Mark in particular, I think we got about 20 minutes into the first interview and he was telling me information that I don’t think I’d ever heard before, and then later confirmed with Tony La Russa and others that no, they didn’t know it either. So in terms of individual stories and personal histories, certainly a lot of that, but then there was a lot that I had forgotten about the race itself. I had forgotten that Griffey was still in it deep into August. I’d forgotten that Sammy had taken the lead in August when they were playing at Wrigley Field. So there were plot points in the story that also sort of had been lost to history in terms of my memory of it, and they were fun to be able to revisit. To rediscover that, “Oh, it was actually like much closer as a race than even I remember.”

How did you get Jeff Tweedy involved to do the score? What did that process look like?

Yeah, I mean, I grew up on the Illinois side of the Mississippi, and Jeff did as well. He grew up in a town about two or three towns south of where I did. He’s a little bit older than me, but I knew he was a baseball fan, and of course now he’s in Chicago. I just thought it was the perfect person who had a similar experience growing up with baseball that I did, and now as the fact that he lives in Chicago, but the St. Louis roots, it was just kind of a nice synchronicity if he was willing to do it. So, the fact that he was down, and then sent us what I think is such an incredible score, was really fantastic.

Obviously when you condense this entire season into a two-hour documentary, there are things that wind up on the cutting-room floor. Is there anything you wish you had the time to include but weren’t able to work in?

First, we interviewed more than 40 people, and everybody’s interviews were great. So there’s a lot of stuff people said that I wish we were able to include — other side stories, or just people’s reflections or recollections. I think certainly the limiting of the time prevents you from getting into certain aspects of the story, particularly things that have happened since 1998, but our goal was really to try to put everyone back in that moment, which is hard now because we know that this took place during the steroid era. So there’s this kind of haze over all of the things that we remember. So we really tried to clear that away for a bit to show exactly what that emotion and excitement felt like, and then take the final act of the film to unpack a little bit of what we’ve learned since ’98.

Going into this, you knew you had to approach the steroid stuff, but what was your gameplan in terms of how you wanted to address it?

Well, I really wanted to take a chronological approach, because I didn’t want it at the beginning, just to lead with steroids or lead with it being a season that is clouded now. I think I wanted to put you back in to the innocence of that time and how it felt and how it seemed. We have a few people sort of hinting that something is coming later, but for the most part just wanted to let it unfold the way it did, which was in the aftermath of the ’94/’95 strike, and at a moment when it was something that baseball and the country really craved. When we get to the moment that the andro [androstenedione] is discovered in Mark’s locker, that’s our first real … that, to me, always felt like the first opportunity to start talking about, not steroids in particular, but about the culture in terms of a gym culture and a weightlifting culture that was developing within baseball at the time that was right in front of our eyes. Everyone taking supplements and suddenly gaining this huge amount of muscle mass, but we didn’t really have an honest conversation about what we were looking at. So that to me was like the moment of saying, “Here was the thing, and people did discuss it. It was a national story.” It was, as you see in the film, the front page of New York’s newspapers. But as T.J. Quinn says, for four years after andro, nobody talked about it.

Towards the end of the doc, we see Mark McGwire getting inducted into the Cardinals Hall of Fame, and it kind of reminds us of this tension between Sammy Sosa and the Cubs and the differences in their legacies with regard to their specific ballclubs. Why do you think it is that McGwire’s kind of been largely forgiven but Sosa hasn’t?

You know, I think that Mark’s decision to make a confession, to do it around with media, including the interview with Bob Costas, where he talks about what he did, when he did it and how he thought it affected his performance. Mutually, not everybody was satisfied by that, but I think that for a lot of people, even if they had conflicted feelings about that season, or about him, it was enough to give him an opportunity to get back in the game and into the Cardinals family. I think his second act as a coach is really kind of interesting in that everybody I talked to at every organization that he was with all said he was an exceptional coach, and that players loved working with him. I know that Albert Pujols and David Freese and others are on the record saying that he drastically helped their hitting. So I think he was given a second chance and then proved that he loved baseball and just kind of put his head down and did that job. I think that’s why St. Louis has embraced him in the way they have. Sammy had a hard break from the Cubs. It was not a beautiful parting, and I think the fact that it’s not the ownership that was there when he was there, it’s a new ownership who didn’t experience the highs of Sammy in ’98, ’99, that they only are sort of in the midst of the aftermath, they had put some kind of condition on Sammy being able to come back. You don’t really see that with any other legacy players, but that’s the situation they find themselves in at this moment. Hopefully that will change.

I read that when you approached Sammy Sosa that he has a list of questions about the project when he was considering getting involved. What were some of the questions that he had?

“Why you?” “Why should you do this?” I remember he said, “Why ESPN?” I think he maybe wasn’t totally familiar with all of the 30 for 30 projects. I don’t remember all of them. I know he was asking a lot about Mark, and whether Mark was going to do it, and would he and Mark do something together, but yeah, it was a solid list.

I know that COVID-19 impacted the timetable for your release and you wound up doing all the final edits yourself. What was that like?

Yeah, it was crazy. I already was going to take over the edits because my original editor was going on paternity leave. So it was tasked to me, and I’ve edited some of my other films, I’ve edited for other filmmakers, so I was excited — a little daunted because I had never worked with Premiere before, I’d always worked in Final Cut Pro — but excited to dive in and finish up the film in time for Tribeca, where we found that we were going to have our premiere. When we discovered that Tribeca was going to be canceled, we’d been working so hard just to get the film finished and ready, and we still had archival that was coming in. So I was seeing new stuff that I wanted to include. Every time you put in a new piece, you have to restructure it. It was a huge task. So when Tribeca was canceled, we all were just kind of like, “Well, we have a moment to take a breath, and we can step away for a second” — which is always good when you’re making a film, to get a little bit of distance from it. But then ESPN called like two or maybe three weeks later and said, “We’re going to move The Last Dance up to April, and instead of your film airing late in the summer, we want to do it in June.” So then it was right back into full post-production, and I was not able to be in a room with my collaborators. So I was learning new technologies that I’d never used before to be able to watch the color correction or the sound mix or whatever else. It was a big challenge just to be able to finish in time, but we did finally got it to ESPN.

The title Long Gone Summer really captures that feeling that a lot of us have about that home-run chase, which is that we’ll never see anything like it again. When Barry Bonds hit 73 in 2001, it felt different. Why do you think that is?

Well, one, I think, again, you can’t discount the fact that it was Mark and Sammy, and inner-division rivalry and the contrast of personalities. That was just something that people loved, and they loved the way those two interacted with one another you see in the press conferences. I mean, people just were excited about them, and excited about the chase, and excited about the game. I don’t know Barry all that well. I mean, I don’t know him at all, but I don’t know his history as well as I do these two guys. I think one thing about that chase that we maybe forget in 2001 is he set that record after baseball had been shut down for a period after 9/11. So, when you see him hit 71, and then later 72, 73, that is in less than a month after this kind of traumatic event has happened in the country. So, I think that might also have had something to do with it, that we had our minds elsewhere. As much as baseball was probably a bit of a salve in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, it still was happening while we were really thinking about a lot of other things.

What do you ultimately hope that people get out of this film?

Well, I think if you were too young to experience it, or didn’t remember all the details, part of it is just to remind that this may be the last massive sporting event that becomes a cultural event as well as just sort of feeds into every aspect of our cultural experience. Now, we have so many different options for entertainment or things to pay attention to, it’s hard to think about something like that coming again that would dominate the culture in the same way. So, I really wanted to sort of remind how big it was and the reasons why it got that way and put you back in those moments. I think, now, also we’re getting to the point where we certainly haven’t stopped talking about steroids in baseball, and that’s going to be an ongoing conversation, but as we gain a little bit of distance from the ’90s, hopefully we’re able to put what we’ve learned about that time period through a different lens, and with an appreciation for the fact of all these supplements being used, the fact that this gym culture, bodybuilding culture had come into baseball in front of our eyes, and we had sort of just not paid attention to it. You know, I think those are things I think if we just see a little bit more clearly what was going on, maybe our conversations around that era can also be a little bit more distinct.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.