“It’s so obvious what skateboarding is. It’s a thing for Californian stoners to do,” Kyle Beachy says, irony ringing through the phone. Beachy, who is a professor of Creative Writing at Chicago’s Roosevelt University, has been skating for more of his years on this planet than not. In his new book, The Most Fun Thing: Dispatches from a Skateboard Life, he considers the role of the sport in both American culture and his own life.

In a tone at once erudite and deeply passionate about his subject, Beachy asks readers to look at this oft-maligned subculture with new eyes and imagine it beyond shallow stereotypes. “It’s not just this person [who’s] interested in smoking weed outside the convenience store,” Beachy laughs. “This is a person who’s engaged in a practice toward some sort of growth.”

As skateboarding takes up space on larger and larger stages — most recently, of course, in Tokyo, where it made its Olympic debut — Beachy examines it as a cultural force worth our time, energy and interest. “I think what has limited a lot of the pursuit of skateboarding seriously is a lack of curiosity,” he says. “There’s real risk in the obvious. What if, instead of being a gate to knowing more, it was a challenge or an invitation? Everything we think is obvious could just as easily be a new curiosity.”

Indeed, in telling the stories and analyzing the mythologies of skateboarding — how it’s been commodified, how it presents the possibility for artistic and personal growth, how it’s affected his own life — Beachy presents skateboarding as an essential part of the fabric of American life.

InsideHook spoke to Beachy about The Most Fun Thing, skateboarding’s literary and athletic presence, nostalgia, DIY culture and whether or not he’ll ever skate handrails again.

InsideHook: Why do you think we don’t get literary writing about skateboarding more often, the way we have in the past about other sports?

Kyle Beachy: What I take as my North Stars are a few authors who wrote seriously about skateboarding from academic fields. Iain Borden came at it as an architectural theorist. Ocean Howell, the former pro skater, wrote beautifully about it in terms of sociology and urban planning. You’re right, there has been hole or vacuum [with regard to] a more literary approach — and I mean literary there not as a qualitative thing, but just in terms of the questions and the interests of literature — and I don’t know exactly why that is. At some point baseball crossed over from being an activity for children to play and maybe a few lucky adults into being this part of the American mythology, so to write about it seriously is to write about more than baseball. The baseball writers I love the most are those who are are able to ignore some of the noise around baseball and really poeticize the game itself. So why not skateboarding? The easiest answer I think here is probably the best, which is that nobody takes it seriously. It’s been a running joke for a long time and a set of tropes to really quickly define a character: the stoner/burner, the child stuck in the teenage or young adult’s body. It’s been this cultural laughingstock for so long.

What do you think will be lost and gained as skateboarding gets taken more seriously and appears on larger stages?

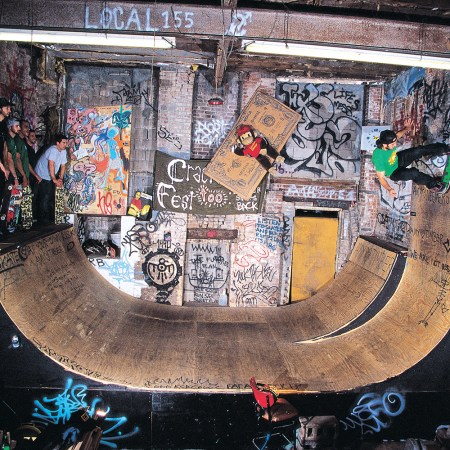

I think the great thing about any DIY culture is that they create their own micromarkets as a defense against the great encompassing macromarket. I think what we’ll see hopefully is hyperlocal production of goods and practices. It’s not just that skaters in Spokane, Washington, are going to have their own board brand, but probably they’ll have their own zines, and probably their own DIY pop-up concrete illegal spots they’ll work toward.

I think the good-slash-bad news of the proliferation of skateboard parks in all of these cities is that it continues a narrow cultural expectation of what skateboarding is. That narrowing creates a broader playing ground for those of us who don’t want to exist in that narrowing lane. This has been the great counterargument to concern about the Olympics, and concern about whether it was Nike coming in or their corporate growth of skateboarding. There will always be weirdos, there will always be people in the margins pouring concrete in some abandoned slab under an overpass in some grungy part of the city. As long as those practices remain, skateboarding’s gonna be fine. Skateboarding creates space for ambivalence and that’s the important thing. Skateboarding allows contradictions, it encourages ambivalence. Where it gets messy is where we start having discourse, which doesn’t really allow for ambivalence. Discourse wants us to make an argument and run with it, but skateboarding itself is conflicted, it’s contradictory, it’s weird, it waves, it changes from moment to moment. We need to find a way to talk about it that encourages that same waviness, ambivalence and contradiction.

How do you see your book fitting in with those ideas?

I think my book is deeply conflicted. One of the things that has to happen in a book that takes 10 years to write [laughs] is changing minds, evolving ideas, backtracking on earlier concepts and revisiting them with new, more informed and mature eyes. One of the things I like about this book as it relates to skateboarding is that I change over the course of that decade. The easiest way is that I age and skateboarding gets harder, but some of the early chapters I think convey a suspicion and protectiveness where most of the later chapters feel a little more in awe and wonder of this thing, realizing I don’t need to protect it, that it’s magical. Then digging in and figuring out what this magic is.

The other thread of this answer is form itself. The essay as it exists qua the essay is the form that encourages digression, backtracking, iterative movements and confusion — not essay as thinkpiece with this underlying thread of argument. If my book has an argument, it’s that “Hey, skateboarding is way more interesting than we’re giving it credit for, let’s look at it.” I’m not dictating policy. I’m not dictating much, except for a continued movement toward inclusivity in skateboarding that has in the past been exclusive.

How do you think skateboarding has influenced you as a writer, beyond just subject matter, and vice versa?

I think that the frustrations I encountered trying to narrativize skateboarding in a very real way opened the door for a new style of writing for me in the form of the essay. I decided as a young person what kind of writer I wanted to be. Being a skateboarder yanked me out of that very narrow idea because I’m much more a skater than I am that kind of writer. In that sense, I learned a lot from the practice of skateboarding. It forced me to reconsider some pretty narrow decisions, choices and definitions I made in the past. Along the way, writing has presented challenges to skateboarding, too. What I was able to do was open up some of that critical lens and again start thinking about my writing as being pursuit and appreciation more than critique and analysis. Once I stopped doing analysis, skating benefited from my writing. Once my writing opened up, then I was able to skate with more wonder, openness and appreciation than before. There has been this real, complex relationship between the two, and ultimately skateboarding has been the winner [laughs]. Turns out that skateboarding is a bigger and healthier force in my life than writing specifically for publishing’s sake.

I think what I allowed for [with this book] is the potential for love. Along the way, part of my question was, “Why do I keep doing this thing?” That question of why was tinged with concern that maybe there was something wrong with me, like I’m still skateboarding because I need to hold onto this part of my youth. I think along the way of writing the book, what I came to see is no, actually, this is a love, and it’s a love for an object that is worthy of that love.

How has skateboarding affected your perception of how and when people grow up, and how do you think it affected your own personal growth?

In my own experience, skateboarding has occupied this realm of nostalgia. That’s not least of all because that’s how the skateboarding industry has sold itself. It is the outcropping or the product of this great Californian mythology. It was always pointing backward to itself and doing a lot of its industrial, commercial work that way. At a certain point one realizes that the nostalgia being sold to them has a nefarious purpose [laughs]. So maybe there was a break that happened as I wrote more about it and tried to figure out what skateboarding is. I became more aware of and suspicious of its rooting in nostalgia. That theoretical awakening led to more subjective and personal awakenings. Also, there’s the very real physical evolution of, I can’t jump down things anymore. I will not jump a handrail ever again. I can no longer smoke weed and go skating and have that be pleasurable. I needed to change my practice of skateboarding. The limitations of the body, of the memory, and the liver, we could say [laughs], made me realize no, I have a new relationship with this thing. Whatever nostalgia offers us, it is stunningly beautiful to look at a thing anew and realize, “Oh, I still love this, I still want to do this.” I think that became its own beauty for me.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.