It is easy to be a bad drummer. In fact, ironically, the more adept you are at the instrument, the more chance there is that you will suck.

See, a guitar player has (usually) 132 different places to put their fingers, but they are never going to insist on touching all 132 spots during a single song. However, a drummer, oh baby, once they know that they have all those things to bing and bong and smash and thrash and thump and stomp, it’s very hard to hold them back. They really want to let you know they can hit all of them! This causes a lot of them to stink.

Truly great drummers, who must master power, discretion, invention, and restraint, are extremely rare and must be celebrated.

Two of the very best drummers who ever lived died this week.

See, friends, death is inevitable. Every great artist, or cheerful CVS employee, or trainer of horses, or K-pop star, or seller of Halal foods will die; yes, that’s true. And although the hours of the day march with the slow logic of the cosmos, the events that scar these hours are a crazy quilt, a spinning wheel flying up and down Escher stairs. So I will not call this a coincidence, this extraordinary fact that two drummers of historic skill died within days of each other; but it is still, you know, what it is.

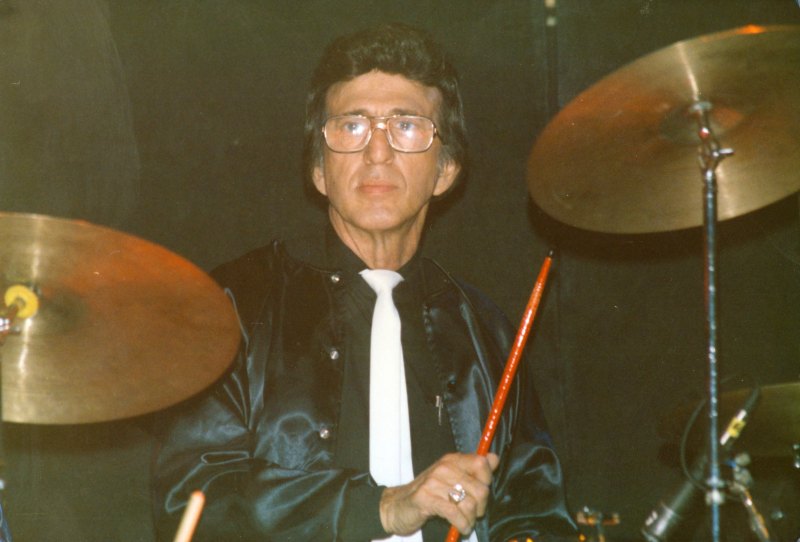

D.J. Fontana (Dominic Joseph Fontana), March 15, 1931 – June 13, 2018

D.J. Fontana, who played with Elvis Presley (Elvis Freaking Presley) between late 1954 and 1968, may be the best drummer that you’ve never actually noticed. When you’re listening to Elvis, it’s very damn easy to be totally focused on this hiccupping, operatic hillbilly sexolution (not to mention twanging, snapping, snarling guitarist Scotty Moore). Even a seasoned listener might not notice the true genius and trickster right alongside Elvis and Scotty who, in many ways, is writing the script and running the show.

Fontana is a deeply sensitive ensemble drummer. Like Keith Moon (whom he resembles in ear, if not in style), he frequently played with the vocalist (as opposed to the bassist or guitarist), picking up on vocal phrasing, rhythm, and lyrical cues. At times Fontana is almost playing a talking drum, implying power but actually doing quite subtle things that tell a story. His drumming really sings and speaks. Fontana also took the hillbilly/Cajun emphasis on the 2 and 4 (which he consistently played with a slight but syncopated rush of the snare hit), creating a “hop” beat that became a clothesline Presley could hang his songs from.

D.J. Fontana was almost always doing something, and once you become aware of his presence, the listener has trouble not focusing just on him. He’s virtually a jazz drummer, always thinking, hopping, flicking parts of the kit on and off like a light show, jumping on and off of the mystery train.

Often, what he played is plain odd — beautifully, functionally odd. Notice on “Jailhouse Rock” how he actually jumped the band’s entry, just by a hair (I’m almost positive this isn’t a mistake or a quirk of the take), and he’s always an eyelash-hair ahead of the beat on every bar; this gives Elvis something to chase, virtually defining the singer’s urgency. Fontana does this, too, on “Treat Me Nice,” where one can almost visualizes Elvis running after a train, knowing he is a better man and singer because he has to chase D.J.

Other times, Fontana falls into a sort of a New Orleans parade beat, filtered through his own expert touch and then adapted to the amphetamined two-step of Elvis’s milieu. In fact, Louisiana is never far from Fontana’s playing; like the great Louisiana drummers, he does magical things without ever straying too far from the floor tom or the floating tom, infusing virtually everything he does with an almost tribal drive, a constant reminder of the original function of drums to lead, inspire, communicate, and warn.

Nick Knox (Nicholas George Stephanoff), March 26, 1953 – June 15, 2018

You know how sometimes you’ll see a movie and someone will tell you it’s actually based on some ancient myth or saga? How many times has some allegedly helpful boyfriend/girlfriend/teacher in a corduroy jacket reminded you that Harry Potter and/or The Lord of the Rings has something to do with “The Hero’s Journey” and/or Joseph Campbell? And don’t even get me started with The Godfather and the Babylonia Succession myth …

Well, The Cramps were a distillation of everything cranky, ecstatic, pure, primitive, exotic, erotic, artistic and utile in America’s indigenous rockabilly, hillbilly, jump blues and garage music. Listen, they were not a punk band: Punk was a minimization, a reduction. Rather, The Cramps were (and I say this in the very best possible way) a fantastic radioactive bolus of sh*t-turd, what happens when everything goes in one end and comes out the other.

Ah, that turd was full of the diamonds of history. That Cramps-turd contained the corn kernels of our cultural legacy, everything that came off of the slave boats or out of steerage and ended up in Yancey County, Eunice, Beale Street and Congo Square, where it began to swing it’s disenfranchised ass to a big beat in order to create an identity apart from the one imposed on it by it’s social and economic captors. Got it, babies? Good. Because if you rephrase that paragraph, you can really impress Professor Gipson in your Introduction to Folklore class (that is, if you go to the University of Wisconsin).

Mostly, The Cramps revived the leering, wide-eyed, erotic spirit of artists like Roy Brown, Louis Jordan, and the Treniers, and re-visioned them through American primitives like Hasil Adkins, Warren Smith, Link Wray, the Collins Kids, and Captain Beefheart. But it didn’t stop there. The Cramps then took that and splat it on the incomprehensibly filthy low-grade porcelain of a doorless toilet at Max’s Kansas City.

It all could have been an incomprehensible mess (especially in light of the fact that prior to 1986, the Cramps performed without a bass) if drummer Nick Knox wasn’t there.

Knox joined the Cramps in 1977, remained until 1991, and he plays on virtually all of their most loved songs. Knox’s job was to take this feral, long-clawed sweat-spasm of a band and nail it to the floor to keep it from disappearing into dissonance or irony.

During the Knox era, the Cramps made some of the most perfect recordings of all time. “New Kind of Kick,” “The Crusher,” “Garbageman,” “Goo Goo Muck,” “The Way I Walk,” and “Domino” aren’t just rock’n’roll recordings; they are rock’n’roll, almost a definitive example of the salted caramel core of the entire f*cking genre. Shaky, shimmering, wiggling, slurring, arrogant, frightened and frightening, it is the American tremble and shudder, amplified, profaned, and tagged.

Many years ago – this is a true story – I locked fey Broadway-bound aesthete Duncan Sheik, then at the beginning of his career, in a car. I then played him the Cramps’ “The Way I Walk” at incomprehensibly loud volume and announced, “Now, THAT’S what a record is supposed to sound like!”

Consistently, the Cramps were held together by Nick Knox’s big beat, and his auTOMatonic aTOMic playing also succeeded in replacing the bass in the Cramps; he held up the entire bottom end of the band. We should also note that Knox, for all his tom-centric tribalism, is not a naïve player. This separates him, hugely, from the two fantastic drummers he most (superficially) resembles, Moe Tucker of the Velvet Underground and Klaus Dinger or Kraftwerk, Neu!, and La Dusseldorf. Knox isn’t just picking up sticks and thumping the Apache beat into submission, as Dinger and Tucker do; rather, Knox knows exactly what he’s doing and what tools to use, like a painter who has trained for a dozen years and then chooses to just paint a canvas black.

Also, Knox knows when to change up parts for emphasis or mood, and he does this with precision and intent. Please note his very deliberate alteration and variety on “New Kind of Kick” (Knox is changing parts far more frequently than anyone in the band, which elevates this classic from trash into rapture), and listen to Knox’s absolutely control on “Garbageman.” We may hear him just thumping the toms, but he is doing this with a nearly delicate, highly musical precision, almost like he is reading from a score.

Although it seems logical (and convenient) to compare Nick Knox to Dinger, Tucker, or Meg White, Knox’s precision in the service of aboriginal power makes him far more comparable to Bobby Graham or Martin Atkins. Both Graham (a legendary English session drummer who plays on the biggest hits by the Kinks, Dave Clark 5, and Them) and Atkins (the fearsome yet thoughtful and adroit drummer who has done outstanding work with PiL, Nine Inch Nails, Ministry, Pigface, and Killing Joke) made intelligent, delicate, and musicianly drumming appear to be cloddish and primitive.

When these two elements align – a historic artist or band with a stellar and distinct drummer who is willing to serve the needs of the ensemble – you really have something remarkable. You probably do not “think” of either D.J. Fontana or Nick Knox when you hear a song by Elvis or the Cramps; but what they did was absolutely essential to the artistry of these giants.

Dedicated to Eddie Ecker, one of my favorite drummers and the man who taught me so much about the instrument.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.