Lost in the evergreen stories about New York’s gentrification eating itself like some perverse cartoon Ouroboros are how it eventually erases any evidence of the weirdos and eccentrics, the one-of-a-kind characters who couldn’t have come from anywhere else.

The people portrayed in the profiles of late New Yorker columnist Joseph Mitchell fascinate me for the same reason—a Harvard-educated hobo author who made the rounds to art parties promoting his own ‘longest book ever written’ that nobody has ever seen, a brazen box office matron on the Bowery who watched every sort of seedy patron and roustabout with a nonjudgmental omniscience, multiple generations of McSorley’s bartenders—immortalized personalities like these preserve our town’s culture. They were our archivists, historians, and keepers of ephemera, full of fascinating memories that could never be converted into the ones and zeroes of Internet ubiquity.

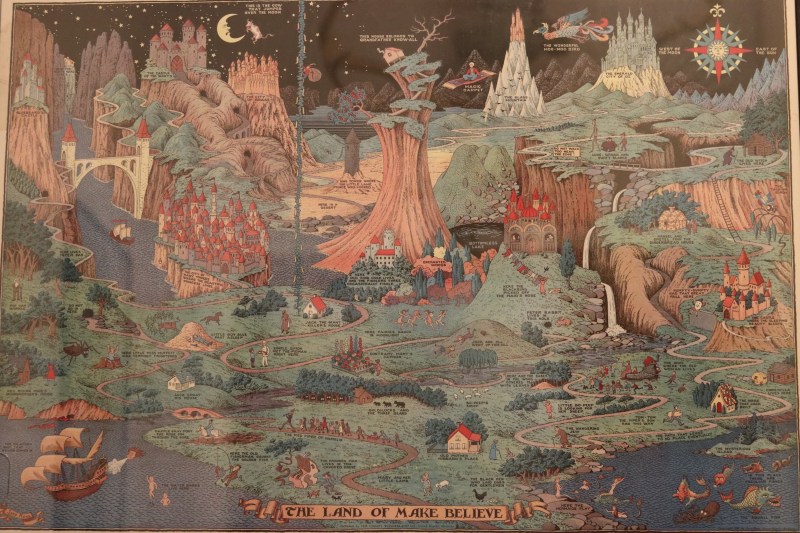

Walking into musician Peter Stampfel’s SoHo loft, ephemera smacks you right in the face. His walls are lined with bookshelves, curios, and endless artifacts infused with stories that veer off into specific times and places. There’s a cover of the first collection ever published as “sci-fi”, edited by Peter’s late father in law who would later start a sci-fi publishing company, DAW, now headed by Peter’s wife, Betsy Wollheim. A bookmarked copy of Ages of The Moon, a play written by his late friend, Sam Shepherd, sits on his kitchen table. There’s a black and white photo of Peter riding a miniature horse as a boy right next to the toilet in the bathroom. In his office, a gas mask made for a horse hangs above a pair of caribou antlers, and on the opposite wall, an illustrated poster depicting “The Land of Make Believe.”

At 79, Peter resists living in the land of make believe by genuinely loving the hell out of each item he and his family owns. He’s an avid collector of many things—bottle caps, sculptures, comic books (he owns over 20,000)— but it’s his music I came to learn about. A 1961 ad for a show of Peter’s, playing what was perhaps for the first time described as “Americana music”, leads him into a remembrance of the first time that the word “Americana” was ever written down. Later in the evening his daughter, Zoë, helps him pull out a framed copy of a typed-out, tongue-in-cheek 1967 “Rules For Fugs Concerts” written by his beatnik yippie contemporaries and occasional bandmates in The Fugs, one of the most schlocky, political, and proto-punk bands to come out of ‘60s New York.

Over the next two hours, I come to learn just how lucid Peter’s memory is of the near-60 years that he’s spent in this city when he brought a genuine love of American music old, arcane and goofy to a staid and serious ‘60s folk scene with his fiddle playing and banjo picking. I also learn how he’s still steadily churning out fantastic records to this day, with Zoë along for the trip.

“About ten years ago, They Might Be Giants called and wanted to know if I would open for them on a tour,” Peter tells me. “They were starting with a couple of upstate New York gigs, which were accessible, so I asked if I could come with my daughter. She had a boyfriend who jammed and was a Phish-head and was awful, and she would go along with him when he was jamming with his friends. One day she was bored and started pounding away on his guitar case and everyone said, ‘wow, do that some more!’ So she came back to town, told me, and I immediately bought her a djembe.”

Zoë stuck around as Peter formed his newest group, the Atomic Mega Pagans, which also includes Hubby Jenkins of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, whom Peter met while down in Red Hook, Brooklyn at the folk/roots institution The Jalopy for Wednesday Roots and Ruckus night. “I hear this guy playing Charlie Patton’s ‘Shake it and Break It’ and think, ‘that guy is really doing a great job, lemme see who this guy is,’” he says. “We’ve been playing together on and off ever since.”

The Atomic Mega Pagans also cover Charley Patton’s “Mississippi Boll Weevil Blues” on their recent album, Cambrian Explosion. “ I didn’t even know it was Charley Patton when I first heard it on The Smith Anthology (of American Folk Music,)” says Peter. “I’d never heard of Charley Patton back then, but it struck me as bring proto-rock’n’roll, maybe the first rock’n’roll record ever. I mean… it’s so elemental and simple, driving and perfect.”

In addition to a new, finished AMP record, Peter’s also got his third release with anti-folk songwriter Jeffrey Lewis in the can. Then there’s the record he cut with Lewis and the late Tuli Kupferberg of The Fugs. Lewis befriended Kupferberg in the ‘90s, they hung out a lot, and Kupferberg showed him a bunch of unreleased songs along with tunes that someone else sang on a later-period Fugs record. They started recording the songs during Kupferberg’s birthday celebrations every year, and Peter would come sit in on them during the final sessions. They’re thinking of calling the group “No Deposit, No Return” after one of Kupferberg’s tunes.

“The variety of Tulie’s songs was far surpassing what I thought it was,” Peter says. “I knew ‘Morning, Morning’ and ‘Nothing,’ but had no idea that he wrote such a wide breadth of songs, and how amazingly beautiful a lot of them were.”

In 1964, the same year that The Fugs’ First Album was released, Peter and Steve Weber released their first record as The Holy Modal Rounders. Their giddy disregard for formality and liberal interpretations of the traditional were a massive middle finger to what Peter saw was a culture too far up its own ass, and they became cult heroes for it.

“Well, the whole folk music scene was very serious,” he said. “On one hand, you had the political side of it that was very self-righteous, then you have the schlocky Kingston Trio/Brothers Four kind of thing—I hated that shit. Anyway, the traditional people tended to be really serious. You had to sound like an old record, down to the scratches, and you had to reproduce it authentically. That word wants to make me fucking strangle somebody. It’s such bullshit—the most authentic thing you can do is make yourself fucking up.”

Peter found a great deal of goofy inspiration in old novelty songs by folks like Spike Jones, who would tear up old standards with sound effects, theatricality and other wackadoodle elements. “He would mock music and tear it apart, but in a totally amazing, exciting way. The only time I was unhappy was with [his version of] “Holiday For Strings”, one of the most exquisite compositions of mankind. He does a rude version of it that I still find offensive. ‘Hey, get your dirty head out of that beautiful object!’”

With this disdain for stuffy formalism, Peter and Steve Weber created a new, weird canon of American folk music. Much of this informality came from the fact that he learned a lot of the songs from old “78s, which were not so easy to understand. In the event that he couldn’t make a line out, Peter would just go with what he thought he heard.

“In any case, I eventually found out what the real words are, and in every case, I like my words better,” he says. “Anyway, that’s when I realized that it was totally valid to change the words. I was less sanctimonious, anyway, because I hated how seriously the folk music scene took folk music. And that old shit was goofy as hell—Dr. Smith’s Champion Hoss Hair Pullers and The Fruit Jar Drinkers… much of that old hillbilly stuff was very beautiful, and much of it was very goofy. I thought the goofiness was as worthy an aspect as the beauty or this historical, traditional part was— a part of the whole that deserved to be preserved.”

Something similar happened with the word ‘psychedelic’, which Peter heard as “psycho-delic” when the Rounders were the first ever to sing the word on “Hesitation Blues” off their debut album. “No one had used that word on a record, and I thought I could be the person to do it, so I was,” he says.

Though many regard him as a true New York hero, Peter reminds me that he was actually from Milwaukee. He came here after meeting a New York girl in San Francisco in 1959, falling madly in love, and following her back to the city to find she was back with her old boyfriend. But she hooked him up with another ex of hers, and they found an apartment on Clinton Street.

“When I got here in ‘59, hallucinogens and pot were the good drugs, and heroin and speed were bad drugs,” he says. “People were starting to sell pot, and a lot of other people said, ‘No, pot is a beautiful thing that you share! You don’t sell pot, that’s not right.’ But by the late ‘50s they were indeed selling pot. And you could buy peyote, it was legal. There was a coffee house on 8th or 9th called The Dollar Sign, and this guy Baron ran it. He actually sold peyote, he cooked down a button into a double O cap, which the largest size capsule available. So he could actually put one button in a cap, and they were a dollar a piece. That was my first hallucinogenic experience. I had seven of them.”

“This sounds silly, but I believed, as did thousands of others, that if Kennedy and Kruschev took LSD together everything would get sorted out and be alright, which is a real dreamboat theory. It was pretty useless as a political thing.”

Bohemia wasn’t truly bohemian same after the summer of 1962, he says, when a drought of pot and hallucinogens, coupled with an influx of teen runaways, brought an influx of small-time Times Square drug dealers and other outside subcultures down on the Lower East Side.

Peter also recalls that things in LES changed for good with the death of Groovy. “Oh, he was an actual person!” he says. “There was a guy named Groovy, and Groovy had a rich Connecticut girlfriend. When [Ed] Saunders [of the Fugs] moved the Peace Eye Bookstore to Avenue A, he dedicated the old Peace Eye as a crash pad. Everybody knew there was gonna be a deluge of new kids bum-rushing the scene because of all the publicity, and a lot of people here were concerned with looking out for them. Groovy was in charge of turning the old Peace Eye into a huge crash pad, they even had mattresses in the backyard. He was a nice guy who wanted to help. He and his girlfriend were murdered by drug dealers in about August 1967.”

Now, surrounded by all of the things he loves, Peter’s thinking about the fact that he can’t take it with him when he’s gone. “Oh, we’re trying to get rid of cool shit, basically,” he says. He speaks fondly of New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast’s trade paperback, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, wherein she has to go to her parent’s old place in Brooklyn after they die and deal with all of their stuff. “And she said one thing she discovered was that old people should get rid of their shit so their kids don’t have to deal with it,” he says.

I tell him that he’s being very gracious but too hard on himself and that most of this stuff belongs in a museum. I tell him that I can’t imagine his kids feeling that way, but Zoë happens to be right next to us, scanning something in the office. “I mean, when I get old I’m gonna be like, ‘Fuck you guys! I’m not gonna spend the last decade of my life trying to make shit easier for you young people!!’” she says with a laugh.

We listen to a recording they made together that will appear on the next Atomic Mega Pagans record, a heartfelt ditty called “Mr. Love” wherein Zoë’s character laments letting a good man go, and Peter’s character comes in as an instructive voice about the lessons learned from the loss. “And if your love is true, I’ll bring him back to you,” he sings.

I thank Peter and his family for opening up their home and getting weird with me before making my way out the door. “We’re in the weird business,” says Zoë. “Weird is what we do.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.