It’s been decades since Elvis Costello’s “angry young man” period. Since then, he’s cooled off and branched out, broadening his horizons with excellent forays into more adult-contemporary fare like Tin Pan Alley-inspired pop, piano jazz and even the occasional bluegrass record. But on his new album with the Imposters, The Boy Named If (out today), he sets his sights back on his youth, revisiting that transitional period of life he describes as “the last days of a bewildered boyhood to that mortifying moment when you are told to stop acting like a child — which for most men (and perhaps a few gals, too) can be any time in the next 50 years.”

Costello notes that the “If” moniker in the title is an abbreviation for “imaginary friend,” and a deluxe edition of the record comes with an 88-page hardcover book called The Boy Named If and Other Children’s Tales featuring short stories inspired by each of the album’s 13 tracks. But don’t get it twisted: this is not a children’s record. These are tales of adultery, violence and scheming, all told with the wisdom, nuance and clever wordplay we’ve come to expect from the man born Declan MacManus. The concept is a loose one — more like a subtle, common thread than any kind of heavy-handed narrative — and thankfully so, because it gives the music room to breathe.

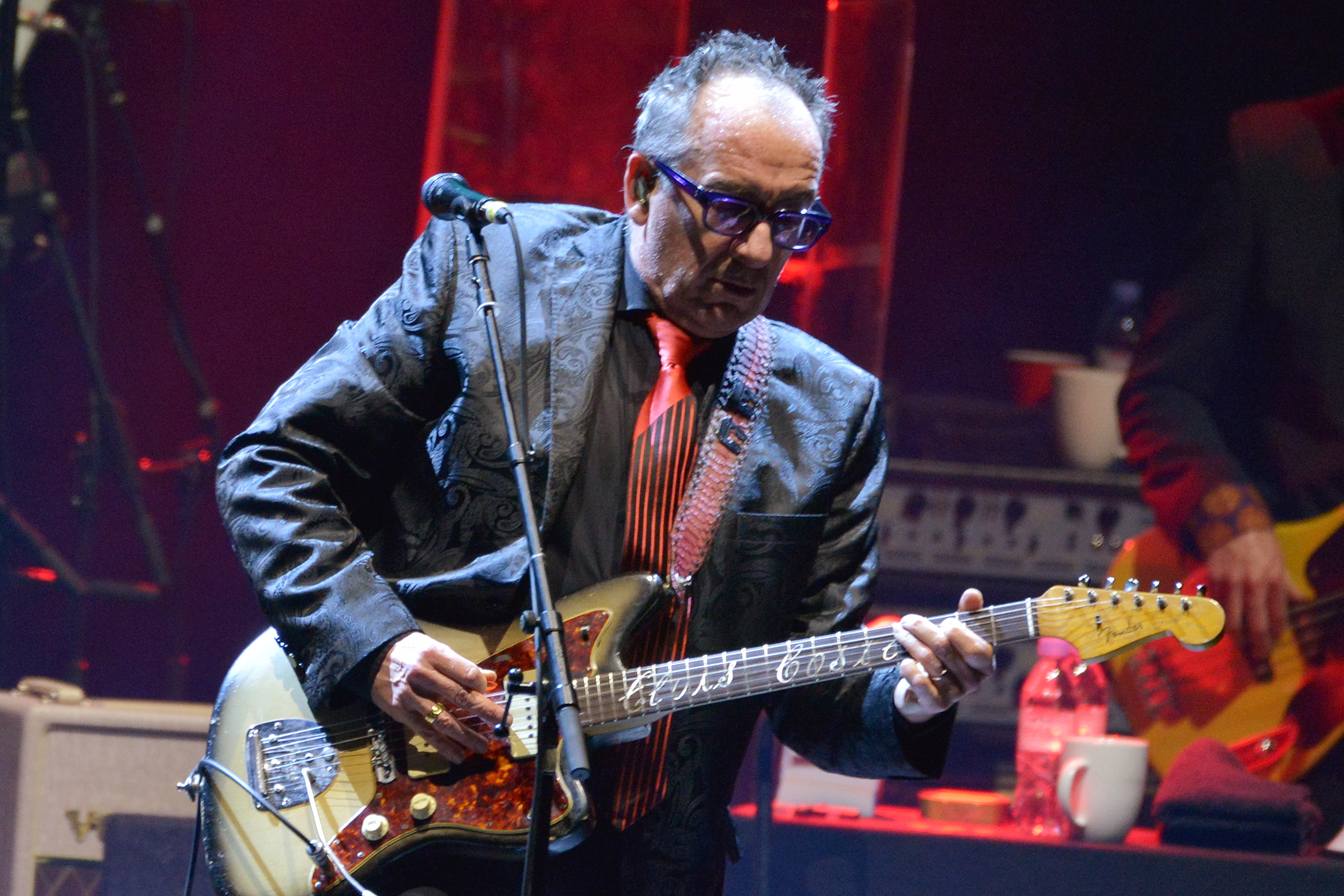

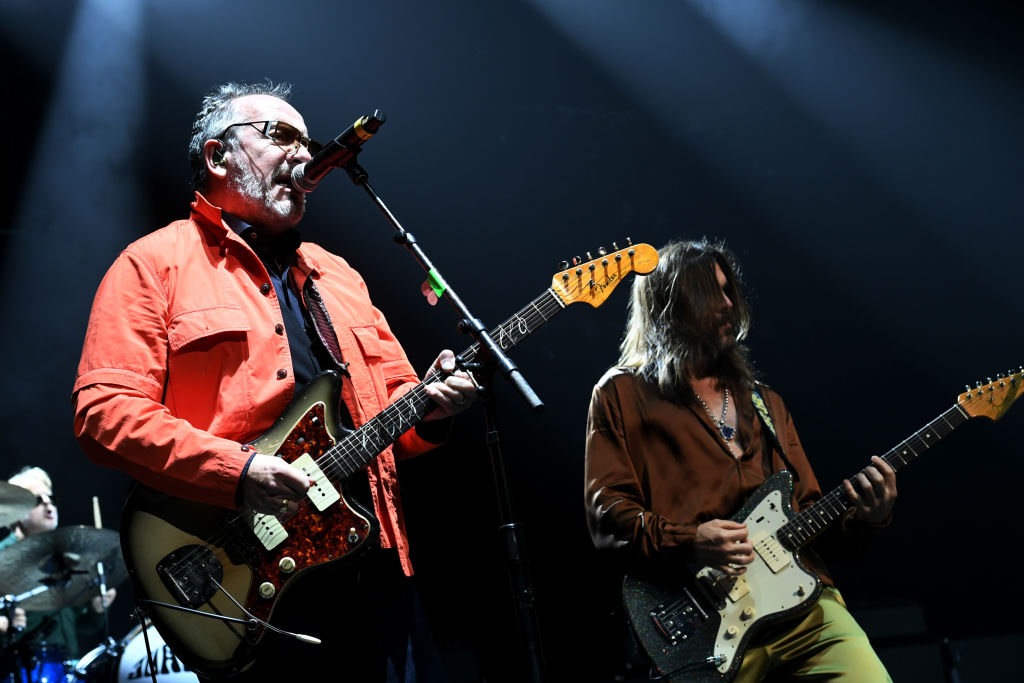

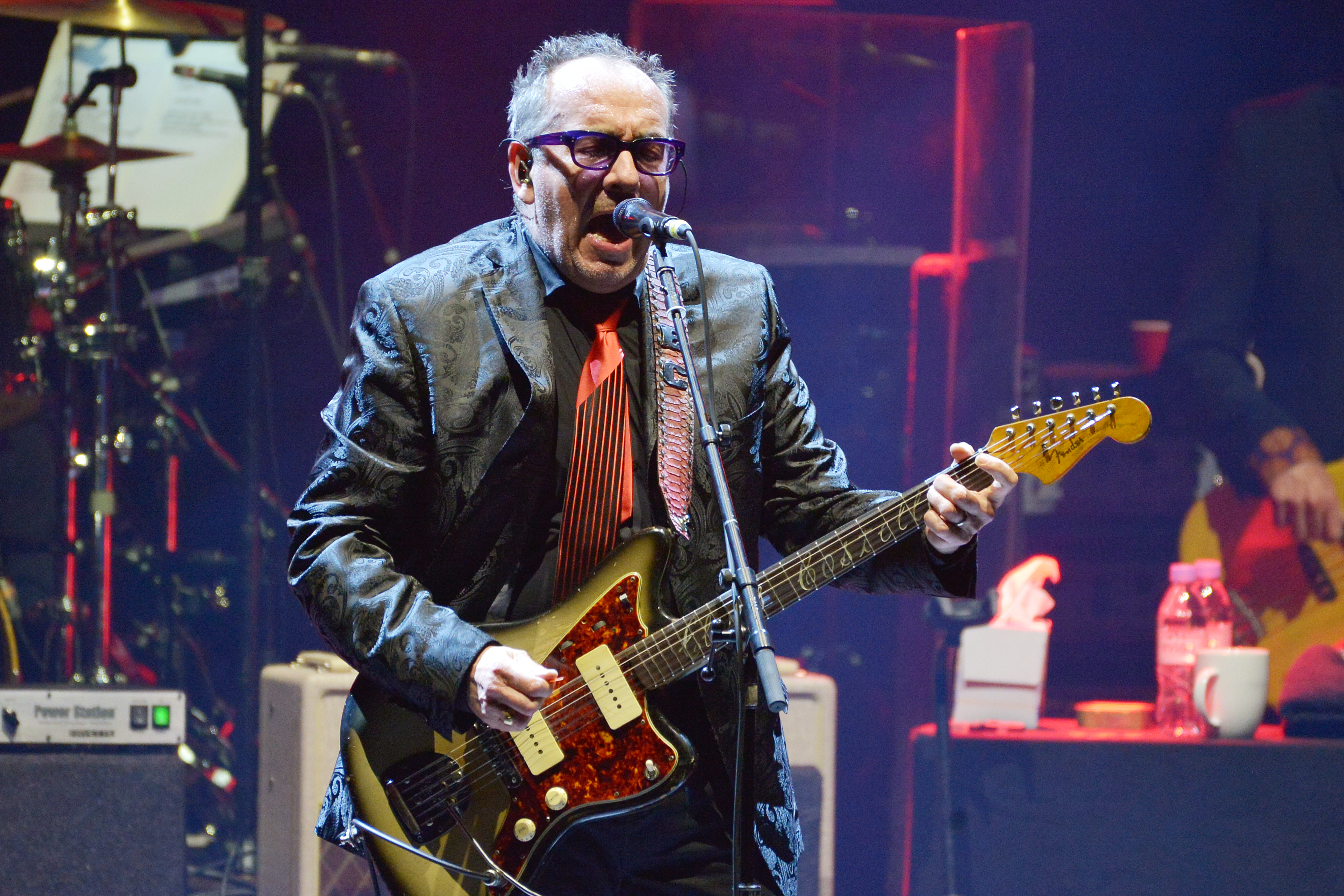

Sonically, The Boy Named If is the closest Costello (and, of course, the Imposters — his classic Attractions lineup with bassist Bruce Thomas replaced by Davey Faragher) has sounded to his fiery late-’70s output in years. You’ll hear traces of This Year’s Model and Armed Forces all over it, but especially on opening track “Farewell, OK,” a sneering kiss-off elevated by Steve Nieve’s familiar organ riffs. “Magnificent Hurt” also sounds like it could have been recorded 40 years ago, in the best way possible; it’s the hardest Costello has rocked in quite some time.

But The Boy Named If isn’t one-note, and there are also ballads and other tracks that call to mind Costello’s more recent output and highlight his stellar lyricism. On the standout “My Most Beautiful Mistake,” which features some guest vocals from Nicole Atkins, he presents us with the story of a filmmaker in a diner trying to woo a “waitress with dreams of greatness.” “He wrote her name out in sugar on a Formica counter; ‘You could be the game that captures the hunter.’ Then he went out for cigarettes, as the soundtrack played The Marvelettes,” he sings. (The waitress, however, remains skeptical: “I’ve seen your kind before in courtroom sketches,” she tells him.)

“Trick Out the Truth” is a sufficiently spooky-sounding Halloween track that evokes the childhood nostalgia of costumes and candy but reminds us that real life has far more terrifying monsters. (Yes, this is a song that name-drops both Godzilla and Mussolini.) Ultimately, it winds up being about the kind of adult anxiety that puts ghosts and ghouls to shame: “What will they say when they haul you away?” Costello wonders. “Will anyone miss you, or kiss you, to say goodbye with a tear or a coin for your eye, when they finally trick out the truth?” The messiness of adulthood also haunts other tracks on the record, like the excellent “What If I Can’t Give You Anything But Love?” (about the end of an extramarital affair and full of casually devastating lines like “When this is over, I go back to my wife and the man that she lives with and that other life”) and “Paint The Red Rose Blue.” Costello describes the latter as “the account of someone who has long-courted theatrical darkness, only for its violence and cruelty to become all too real. In its wake, a bereft couple learn to love again, painting a melancholy blue over the red of romance.” It’s a killer (no pun intended) character study, full of gems that remind us why he’s celebrated as one of our greatest songwriters. “The words that came to him, both the lies and the threats/ They arrived all too easily, but they ran up some debts/From the thunder of a pulpit to the whispers of a lover/Till he found that he couldn’t tell one from another,” he croons.

Ultimately, Costello’s 32nd studio album isn’t so much about a coming-of-age as it is our inner child — not some long-lost sense of whimsy, but that uncontrollable id, all of the base instincts that we’re supposed get better at ignoring the older we get. It’s a record about lost souls and stunted growth and selfish adults who have probably been told to act their age on multiple occasions. In other words, it covers a lot of the same ground as some of his most beloved work. But miraculously, The Boy Named If doesn’t feel like a rehashing of the past or an artist resting on his laurels; it calls to mind old favorites, but it tweaks the formula just enough to keep it interesting, and it stands as proof that Costello can still fire off an essential listen nearly half a century into his career. If this is what this angry young man sounds like at age 67, one can only hope he keeps tapping that well for another few decades.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.