Welcome to the first installment of Behind Bars, a look back at the great drinking scenes of yesteryear. Today, Aaron Goldfarb visits Manhattan in the late-1960s to recount the goings-on at Maxwell’s Plum and the original T.G.I.Friday’s (before it became a chain restaurant), two places that would prove instrumental in the rise of the American singles bar.

Summer of 1965 in New York City. The Yankees were playing like crap. The Vietnam War was heating up. “Satisfaction” by the Stones was blaring on 1010 WINS. Ed White became the first American to conduct a space walk.

But none of this mattered on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where, every Friday night starting at 8 p.m., First Avenue between East 63rd and 64th was shut down by police barricades so the city’s young people could bounce back and forth between bars like T.G.I. Friday’s and Maxwell’s Plum, slugging cheap beers and looking to get laid.

“By midnight on Saturday, it seemed that someone had thrown a frat party without realizing a street fair was already underway,” wrote Betsy Israel in Bachelor Girl: The Secret History of Single Women in the Twentieth Century.

This “singles’ Gold Coast,” as the New York Times labeled it — or “body exchange,” as Newsweek did — would burn bright for a few years, not just changing the scope of nightlife in uptown Manhattan, but helping usher in a new dynamic for male/female relationships throughout the entire country.

“Now it’s not true there weren’t places for women to drink [in New York] at the time,” explains Dr. Jessica Spector, who works on intellectual history and ethics, and teaches about drink culture at Yale. “But women of a particular subset of society, the kinds of women who went to college, didn’t go to bars before this. And then they did.”

While so-called “singles bars” seem like an anachronism in an era of dating apps and #metoo, there was a time they didn’t really exist and, well, had to be invented. By the early 1960s, more and more young people were leaving their Norman Rockwell-esque hometowns to strike gold professionally, socially and — hopefully — romantically in the Big Apple. Many of those twentysomethings were planting themselves on the Upper East Side, which Spector calls a “wasteland” at the time.

“The urban mechanisms for convergence have become defective and the opportunities for boy meeting girl fewer,” wrote Dr. Charles Abrams in his 1965 book The City is The Frontier. “The newcomer to a city may never meet her neighbor, much less a suitor.” More bluntly put, young people were lonely in the faceless city, and the private cocktail mixers of the day weren’t quite cutting it.

Luckily, one intrepid perfume salesman, Alan Stillman, was working on changing all this just as Abrams’s book was hitting shelves. Though his T.G.I. Friday’s is generally credited as being America’s first singles bar — a term not even coined until 1968 — most now agree that has occurred due to Friday’s own paradoxical rise to becoming a family-friendly mega-chain, as well as Stillman’s own skillful self-promotion. New York’s first singles bar had probably actually already opened two avenues over, between East 63rd and 64th, two years before.

“[I]t was on Third Avenue, where all the bars were Irish — neon lights and shamrocks and all that rubbish,” wrote Malachy McCourt in his memoir, Death Need Not Be Fatal. “There was a tradition where they wouldn’t let women sit at the bar; women who did were suspect. I thought that was stupid.”

It was conveniently set just down the street from the pink brick Barbizon Hotel on Lexington Avenue, a female-only dwelling where many aspiring writers, editors, models and actresses of the day stayed, including a young Grace Kelly, Cybill Shepherd and Joan Didion. They’d head down Third to pop in for a pint. As a less-famous bar regular recalled to the Times in 1998:

“The girls came and the boys followed.”

That was Stillman’s strategy as well. In the 1960s, the Upper East Side was absolutely packed with singles — a rough estimate was some 800,000, and a good majority of them were women. That was because most stewardesses from the now-burgeoning airline industry lived on the Upper East Side — close to the Queensboro Bridge and a quick escape to the airports — with many of them residing in a building on 345 E. 65th and First Avenue, one that took the nickname “The Stew Zoo.”

“Girls would fly in and out, in and out; it was a real ‘hotbed’ place. You might have six stewardesses sharing a three-bedroom apartment,” Stillman told me back in 2015. Previous to this era, having more than two women living in one apartment rendered it a brothel in many landlords’ eyes. “If historical markers were posted to commemorate the swinging-single era,” wrote Richard West in a 1981 issue of New York magazine, “one would be affixed to … the infamous ‘stew zoo.’”

The 28-year-old Stillman, then working at International Flavors & Fragrances, was a regular at a beat-up First Avenue spot called Good Tavern. The beer was cheap, the food sucked and women wouldn’t be caught dead there. It was just too gross. Stillman thought he could do a better job, and offered the owner $10,000 to take the bar off his hands. The salvo worked.

Thank God It’s Friday! — a popular phrase amongst the youth of the time —opened on the northeast corner of 63rd and First Avenue on March 15, 1965. Stillman knew the decor was arguably more important than anything else — it had to be friendly and welcoming to women. Thus, he painted the exterior baby blue and hung red-striped awnings, while the well-lit insides offered Tiffany lamps, stained glass and brass rails. Waiters wore bright soccer jerseys as they stalked the sawdusted floor, presenting menus with items affordable and exciting to a young customer — burgers and fries, cheap beer and sugary cocktails like piña coladas.

“[It was] a cocktail party you didn’t need an invitation to,” claims Stillman.

From day one it was packed with singles. By the second weekend, Stillman had to get a movie theater’s velvet cordons to manage a line outside — a line he claims might have been the first in New York City bar history. There was nothing sordid about it all, however.

“These were women doing what men have done for a long time — they were getting a drink after work,” adds Spector. “Men had done it for generations. And, yeah, they were gonna get laid also.”

That part was fairly revolutionary. New York up to this point had been a drinking man’s city. Places like McSorley’s Old Ale House (motto: “good ale, raw onion, and no ladies”) literally only allowed men, something you could still see the remnants of all the way up until 1970, when legislation was enacted barring discrimination in public places on the basis of sex.

These newly established singles bars “functioned as a mainstream counterpart to the political and bohemian subcultures of the 1960s,” believes Jane Gerhard, writing in 2001’s Desiring Revolution: Second-Wave Feminism and the Rewriting of American Sexual Thought, 1920 to 1982. “Whereas young white hippies claimed Haight-Ashbury and San Francisco as their Mecca, Manhattan led the way in servicing upwardly mobile young white swingers.”

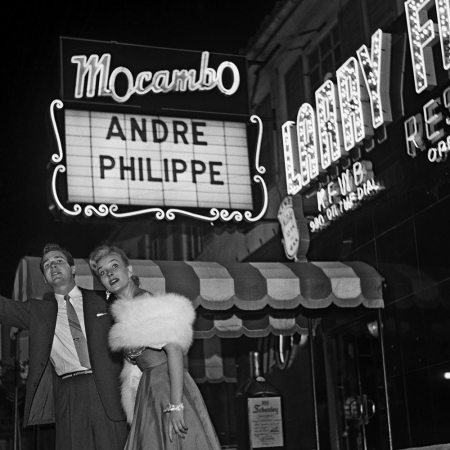

Opening quietly on Tuesday, April 5, 1965, one block north from Friday’s, on the northwest corner of East 64th and First Avenue, there was Maxwell’s Plum. Its owner, if not impresario, was Warner LeRoy, grandson of a Warner Bros. founder and son of Wizard of Oz producer, Mervyn LeRoy. LeRoy was a little less successful than both, an immense, 270-pound off-Broadway producer who favored modish, velveteen suits, gold brocade jackets and silk capes, and who had literally owned Toto the dog as a child (a “nasty little creature,” he said of him).

His restaurant would be equally outlandish, art nouveau-styled with stained-glass walls, 70,000 jewels and antique chandeliers adorning the ceiling, a Lalique fountain, lion’s-head planters, bronze bears and ceramic ocelots. It, of course, also had freshly potted ferns and ample Tiffany glass, surely the most of any singles bar ever, as LeRoy had scored 10,000 sheets of it for dirt cheap.

More ambitious and more of a restaurant than Friday’s, the menu featured everything from oversized hamburgers to Iranian caviar, chili con carne to Burgundy snails. All were apparently good enough to get a four-star review from the Times in a review entitled Yes, Some People Actually Go to Maxwell’s Plum for the Food, their absolute highest score (and one of only five restaurants to have earned it at the time). It was soon serving 1,200 customers a day, including such boldface names as Cary Grant, Barbara Streisand and Warren Beatty, who would order $48 magnums of 1961 Blanc de Blancs champagne. But the so-called Brooklyn secretary was also welcome to come in and drink an ice-cold mug of one-dollar beer.

“By being consciously — almost self-consciously — democratic, by avoiding all pretense to exclusivity, it has become one of the most smashingly successful places in the city,” thought Peter Benchley, the author of Jaws.

It was pulling in around $6 million a year by 1960s prices, a third of that from alcohol sales, making it arguably the most profitable restaurant in the city. Even LeRoy was mingling at his establishment, eventually meeting a TWA stewardess named Kay O’Reilly, whom he would marry.

“The place puts me in mind of W.C. Fields’ definition of sex,” Herb Caen, the columnist for The San Francisco Chronicle, would later write. “I don’t know if it’s good and I don’t know if it’s bad. All I know is that there’s nothing quite like it.”

Imitators soon followed, each trying to capture lightning in a bottle on the Upper East Side, which one magazine had now dubbed New York’s “swingiest square mile.” By 1968, 85 bars called the neighborhood home, like Gleason’s, slightly further uptown near Yorkville, and similarly decorated to Friday’s, with Tiffany lamps and the ornate wooden bar that had graced the Schaefer Beer pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. Daly’s Daffodil, at the foot of the Queensboro Bridge, offered a more laidback scene, with big glasses of Bloody Marys served with fresh cracked pepper.

“It is widely agreed that they [Upper East Side singles bars] marked an all-time low in bar décor, and in beverage quality,” wrote Nicola Twilley of The New Yorker.

There was also Phil Linz, a punch ‘n’ judy hitter for the New York Yankees who was a rare male resident of The Stew Zoo. The infamous “Harmonica Incident” — when he inadvertently refused to quit playing his mouth organ while manager Yogi Berra spoke — had led to Linz getting some quick cash from speaking engagements. He injected that into a place called Mister Laff’s — his nickname — which would become not just a First Avenue singles bar, but Manhattan’s first sports bar. It offered beige-and-green burlap walls and a red slate floor, and every night hosted single sports writers, sportscasters, ballplayers, and, of course, single stewardesses. Linz, like LeRoy, would soon meet and marry one.

“It’s often tempting to say places like these changed the landscape, but they were more emblematic of changes that were already afoot,” says Spector. “That was true of the 1960s in general. People like to talk of the ’60s as when things changed, but those tensions in society were already there.”

Eventually, the First Avenue scene started spilling to Second and into places like Adam’s Apple, with its artificial palm trees, Bloody Marys at 2-for-$6, and matchbooks that offered space inside the flap to jot down names and phone numbers. At Paxton’s Publick House, “they really put a banana in the blender for the fresh daiquiris,” according to the Times. There was also the Hudson Bay Inn, started by an ex-Pan Am publicist who simply snail-mailed all 2,200 stewardesses in the company database to attract customers.

“Second is much more relaxed, more real. A chick can come in here alone and know she won’t get hit on if she don’t want to,” explained bartender “Chipmunk” to the Times. “She doesn’t have to get hassled.”

By the late-1979s and ’80s, the singles scene was changing, however, and moving back downtown. It had become a bit sleazier: disco and cocaine were a bigger draw than a cheeseburger and a Harvey Wallbanger. But wholesome singles bar model that Stillman and T.G.I. Friday’s had engineered was getting franchised and mimicked across the country by then. Not to mention that this first wave of 1960s singles were getting married, leaving Manhattan, and flocking to the ’burbs.

Today, Friday’s original Manhattan location is an Irish pub called Baker Street. Sure, plenty of singles still live on the Upper East Side, where the rent is (comparatively) affordable, but more New York singles these days live downtown, in Murray Hill or Lower East Side, or across the river in Astoria, Bushwick, Greenpoint and Williamsburg, all with bar scenes are better suited to them.

Mister Laff’s closed in 1972, and its former location is now a hair salon; Adam’s Apple is now a mattress store; Daly’s Daffodil an apartment complex. First Avenue itself is never closed to traffic any more, either, save the occasional family-friendly weekend street fair.

Maxwell’s Plum, meanwhile, scrambled to stay with the times, with LeRoy constantly changing chefs and cuisines in the final years, from traditional American to California cuisine, French and even Pacific Northwestern, before finally closing in 1988 — the last holdout of this glorious singles bar era. Its insides were auctioned off the next year, with Donald Trump buying a bronze elephant head for $4,250. Today, the location is a Duane Reade.

“As much as I like Maxwell’s, it’s an awful lot of work to keep it new, and really, for me, the fun is lost,” LeRoy said upon its closure. He could have just as easily been talking about all these singles still playing the dating game.

As he added: “You can’t keep something going forever.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.