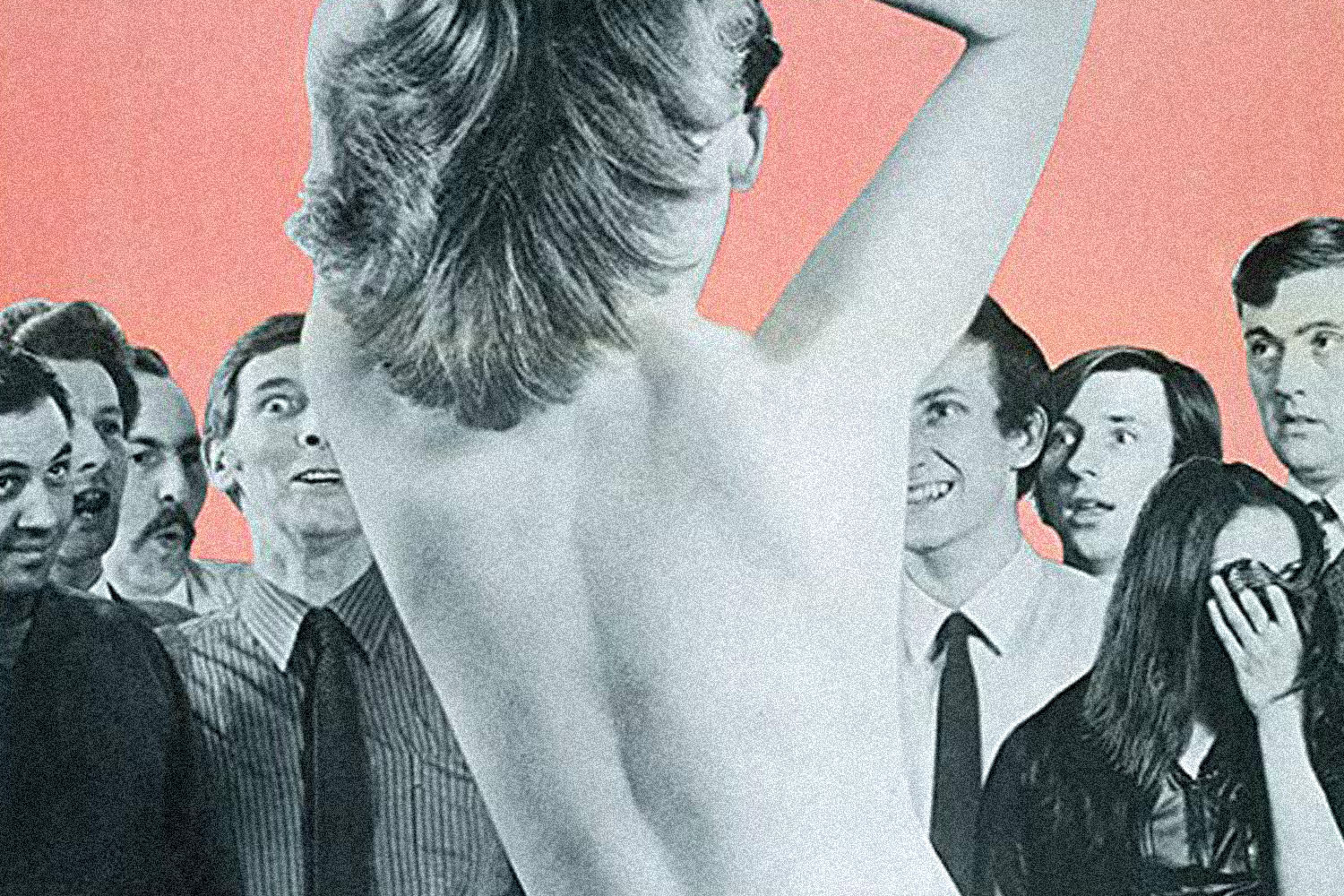

No single work of art in the Western canon has seen its fortunes rise and fall as precipitously as Showgirls, its zig-zagging-leg poster right there in the dictionary under the definition of “film maudit.” Paul Verhoeven’s erotic satire par excellence was initially greeted by critics with near-unanimous revulsion, gradually reclaimed by a devoted cult audience worshipful of what they saw as a lovable badness, and finally reappraised by a faction of critics and academics more inclined to accept its over-the-top sexuality as commentary. This roller coaster ride of legitimacy has been cemented in articles and essays and books and, most recently, the documentary You Don’t Nomi, released this past summer. We have officially reached the point at which it no longer qualifies as an original insight to note that Showgirls may be much better than most people have given it credit for.

But the last piece of this rehabilitation has yet to be completed. Perhaps the most maligned aspect of the initial releasequagmire in 1995 was Elizabeth Berkley’s starring turn as Nomi, a dancer (or is it “dancer”?) with a checkered past and a willingness to do whatever it takes to get ahead in Las Vegas’ sleazy sector of showbiz. Berkley gave a go-for-broke performance of blistering intensity and nearly torpedoed her entire career along the way. She inspired the nastiest critical put-downs and earned not one, but two Razzies. Her agent Mike Menchel dropped her once he realized the damage this reception would do to her public profile, and she couldn’t even get on a phone call with a possible replacement. Even now, among those who champion the genius contained in the film, Berkley’s performance is widely taken as a bug turned feature by Verhoeven’s skillful direction.

Film critic and scholar Adam Nayman, author of the definitive reconsideration It Doesn’t Suck and a key interview in You Don’t Nomi, affirmed that much when I approached him for some counsel on this area of his expertise. “If you respect the movie, or even if you respect reality,” he says, “you don’t want to paper that over too much and be like, ‘Well, in the same way the movie is better than everyone thought, the performance is actually great!’ That’s not where I would go.” (He’s quick to clarify: “I could not love a piece of movie acting more.”) No disrespect intended to Mssr. Nayman, or this fine film, or reality itself, but this is precisely where I intend to go.

The level of vitriol reserved for Berkley at the time was so unusually vicious that it still colors perception of her authority and intentionality. Though Verhoeven had established a body of work substantive enough to earn him the benefit of the doubt from his pockets of supporters, his leading lady had no such luck. When she landed her first proper lead in a feature, she was a 22-year-old actress known primarily for shrieking her way through “I’m So Excited” while bugging out on caffeine pills in Saved by the Bell. Her inexperience, combined with the overt carnality and raw fuse-blowing energy she brought to Nomi, painted a target on her back. The critics readily strung up their bows, unaware that they were often reproducing the sexism they claimed to decry in the film. “As an actress, Berkley is, to put it mildly, limited,” wrote Owen Gleiberman, then of Entertainment Weekly. “She has exactly two emotions: hot and bothered.” Janet Maslin echoed his sentiments in the New York Times, describing Berkley as having “the open-mouthed, vacant-eyed look of an inflatable party doll.” Constructively colorful dissing is one thing — this was just animus.

Posterity has been kind, but there’s still a sense of reservation about the praise she’s earned. In a 2015 interview with Rolling Stone, Verhoeven gave a qualified defense: “People have, of course, criticized her for being over-the-top in her performance. Most of that comes from me. I pushed it in that direction. Good or not good, I was the one who asked her to exaggerate everything, every move, because that was the element of style that I thought would work for the movie.” These remarks reinforce the idea of Berkley as a quasi-witting tool put to savvy use by Verhoeven, the sort of auteur who likes matching role to persona. He tapped Arnold Schwarzenegger as the lead in Total Recall in part for the extra-textual connotations he brought with him, and he’s gone on record that Isabelle Huppert pretty much directed Elle. As a non-star eager to please in her pursuit of fame, Berkley was the ideal vessel for Nomi, a parallel authorized by the star herself at a triumphant 2015 screening in Los Angeles’ famed Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

More importantly, he’s making the point that she’s in sync with what the critic Catherine Bray calls a “pop-art caricature,” a cinematic aesthetic of vibrant fakeness informed by the neon-tree artifice of its Las Vegas setting. “The hate towards her character, an edgy, nearly psychotic character, is actually a compliment,” Verhoeven told the Los Angeles Times in 2015. Anyone calling out Berkley as a talentless floozy only proved the film’s thesis that professional legitimacy and full-frontal sex appeal cannot coexist in America’s culture of repression. But still, the admission that Berkley’s acting may have been mesmerizing and creatively correct always comes with the caveat that she may not be “good.”

“Good” becomes a tricky term where acting, perhaps the form of artistic expression requiring the most subjective and abstract assessment, is concerned. The typical qualities that serve as standards for that slippery concept of goodness, virtues like restraint or emotional realism, have no purchase here. Verhoeven conceived of Vegas as a dimension that transforms everything into a garish, rhinestone-encrusted version of itself, and Nomi had to be absorbed by it. Nayman puts it best: “The way she was directed, her relative inexperience, and her commitment create this perfect storm that, at times, can be quite indistinguishable from ineptitude.” She’s working in a particular form, one with criteria unfamiliar to mainstream movie audiences — like kabuki, or pro wrestling. (I have a theory that audiences are more inclined to give a pass to nonreality in theatrical settings, a sanctioned type of make-believe, than in film, a medium imbued with the visual accuracy of photography. That’s another, less fun essay.)

Berkley’s performance is rich with detail, the hitch being that none of it comes subtly. In a fan-favorite scene early on, she eats a burger and fries like she’s trying to wrestle it into submission. When asked where she’s from, she snaps back like a petulant sixteen-year-old screaming at her mom: “Different PLACES!” To me, this is a comic bit every bit as inspired as Paul Rudd picking up the plate and fork in Wet Hot American Summer. What’s meant to be an overreaction was instead interpreted simply as over-acting, when Berkley was never made to believe that she was facilitating profound human drama in the first place. She was a knowing collaborator with Verhoeven even when taking orders, an instrumental part of the process to surpass plausibility for something more electric. She gave the director what he asked for, and that she was able to do so perfectly should exempt her from “badness” branding. “If you’ve ever been on a movie set or directed theatre, you never just take a bite of the burger,” Nayman says. “You make a choice.”

Berkley refashions “badness” as a workable actorly register of her own devising; one can say that it’s only made good by the context of the film containing it, but the ability to fit aptly into the work containing it has always been the hallmark of all good performances. The ironic phenomenon of “so bad it’s good” applies to those with no congruence to the film they’re in, someone like Tommy Wiseau, an amusing goofball swinging in the dark. A more fitting comparison would be to Nicolas Cage, a Nouveau Shamanic master whose greatest manias have always been organized under a grander artistic project. Even if Berkley wasn’t cognizant of the complexities inherent to Verhoeven’s profane lampooning on Western excess in 1995, she understood precisely what sort of person Nomi had to be. Whether or not she’s a good actor, a designation earned through years of consistency and range-showing, is beside the point. You don’t have to be to spark a flash of brilliance.

“Whether it is a good or bad performance, by whatever metric you want, Showgirls would not be Showgirls without it,” Nayman says. “A more proficient, controlled, successful performance wouldn’t have led to that greatness activated later on, and no one would talk about it now.” I agree with him, at odds mostly on framing, to the point that the whole thrust of this essay may seem a bit persnickety. But the fact that Berkley’s contribution clinches Showgirls means that it is a good performance, just as a proficient and controlled alternative could not be successful by its very nature. Pamela Anderson, Drew Barrymore, Angelina Jolie, Denise Richards, Charlize Theron and a few others all turned Nomi down, but they never could’ve done what Berkley did. (Physically, maybe, though only in the same respect that I am physically capable of painting Rothko’s “Red on Maroon.”) They don’t have the abandon that makes this character and her film. Berkley knew what she had to do, whether or not she knew what she was doing. Her first stroke of genius was saying yes to the job.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.