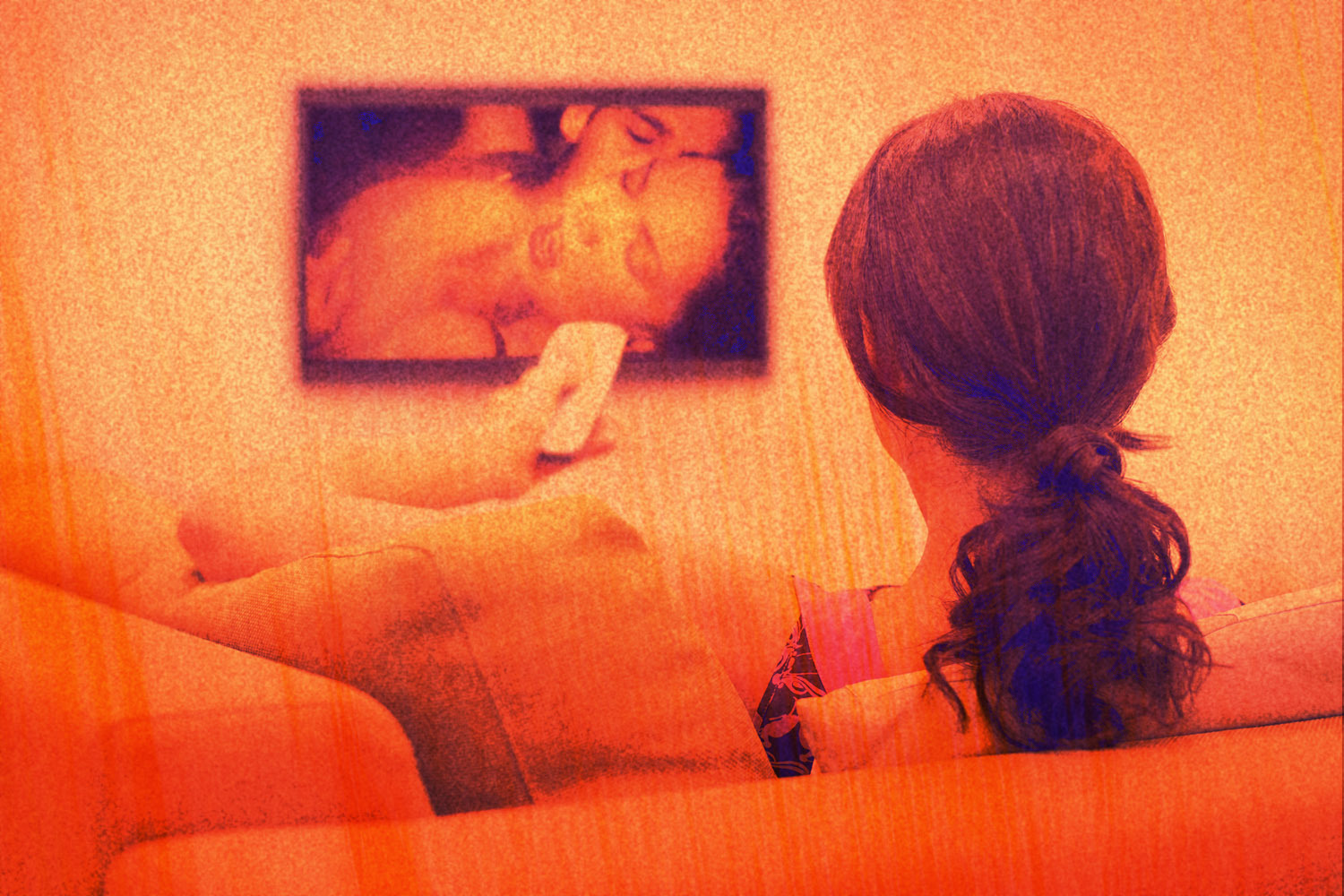

Earlier this year, culture writers got in the mood to talk about erotic thrillers — specifically, about how the release of the Ben Affleck/Ana de Armas movie Deep Water represented a rare instance of a mainstream Hollywood production actually focusing on a sexually charged narrative, rather than gingerly avoiding the depiction of physical intimacy. This dovetailed with a seemingly never-ending cycle of Twitter discourse about the role of sex scenes in films. To the surprise of some movie fans, objections to sex scenes are not always being raised by older, more traditionally conservative viewers, but by younger folks who consider movie sex unnecessary and/or exploitative. No wonder movies like Deep Water are being shunted off to streaming; some audiences are apparently not just acquiescing to but actively demanding a Marvel level of sexlessness in cinema.

Though the new movie Pleasure has been in the works for ages — it began as a 2013 short film, was selected for the 2020 Cannes Film Festival and finally premiered at Sundance in 2021 — it seems custom-made to provoke more of this debate; it may be the most sexually explicit English-language film in years (short of crossing over into “real,” unsimulated sex, as a few indies have over the years). Set in the adult film industry of Los Angeles, it follows recent transplant Bella Cherry (Sofia Kappel) as she attempts to jump-start her porn career, with all of the hustle, sleaze and social-media thirst that entails. It’s a chillier, less rollicking journey than something like Boogie Nights, which looked wide-eyed at its subjects before the drugs and desperation set in. And unlike, say, the Alfred Molina drug-deal sequence late in Nights, the more harrowing moments of Pleasure aren’t “fun” on the level of visceral thrills — though the movie isn’t an overwrought nightmare, either. Director/cowriter Ninja Thyberg casts an unblinking eye on the adult-film industry without necessarily relying on sex-worker stereotypes of childhood damage and trauma. The title comes from the film’s opening, when Swedish transplant Bella is asked at the U.S. border whether she’s visiting for business or, well, you know. Her answer is neither surprising nor accurate.

Pleasure depicts about as much sex as possible within fiction-movie constraints — too much, apparently, for beloved indie outfit A24. The studio acquired the film, only to surrender its rights to similarly hip distributor Neon, following a conflict over A24’s plan to release both the original film and a recut R-rated version. This behind-the-scenes dust-up feels perfectly emblematic of the surprisingly puritanical youth: A24 may inspire cultish devotion, but they don’t expect their fans to follow them into the world of porn. Maybe last summer’s Zola or TV’s Euphoria are as far as they’re willing to go.

Indeed, it’s easy enough to picture the anti-sex-scenes crowd watching Pleasure for 10 or 15 minutes and shutting down completely; in terms of necessity, it’s an all-or-nothing affair that will inspire plenty of viewers to choose “nothing.” Yet in a weird way, the movie conforms to that quote-tweeted worldview about sex in media: There’s hardly a moment of sexuality depicted in the movie that’s anything less than exploitative of someone, even when enthusiastic consent is involved. And the movie makes clear, the latter is hardly a given, even when Bella eventually purports to be up for whatever. When she talks about her submissive role in one scene awakening a sexual preference, it’s hard to tell whether she’s being truthful, trying to sound game for various porn higher-ups or trying to convince herself. It’s not that Bella doesn’t enjoy sex, but in terms of what we see on screen, she looks happiest when she’s Instagramming the, ah, results of a particular sex act, perhaps thinking of the followers the photos might attract.

It’s not Thyberg’s prerogative to make a space for sex-positivity in this world, and Pleasure certainly seems realistic in its depictions of systemic abuses, especially the ways that willing participants can still be cruelly cajoled beyond their comfort levels; even openness can be manipulated and exploited. That’s ultimately more the subject of this movie than sex. Despite the nudity and the fluids, there’s a certain digital-video sterility to the images of Pleasure, and the fact that some of its additional photography took place in Sweden, rather than Los Angeles, only contributes to its sense of an alternate world, adjacent to but decidedly separate from Hollywood glamour.

But that Euro-detachment also feels alienated from the idea that sex might ever be enjoyable for its own sake. (A strange irony, given that the stereotype about European film is that it’s far more comfortable with sexuality than its American counterparts.) For all of the quiet nuances that Sofia Kappel brings to the leading role, and all of the intentional ambiguities about her background as a restless loner with her sights set on stardom, there’s something oddly simplistic, even rigid, about the movie’s moral universe. Some charming scenes of Bella interacting with her tenuous, newfound adult-industry friend-group (all played by figures from the real industry; newcomer Kappel is basically the only performer in the cast without a porn dayjob) seem to cry out for a filmmaker closer in sensibility to Andrea Arnold or David Gordon Green — someone more interested in teasing the messy humanity out of the potential misery. Thyberg seems less interested in her characters than what they do (and what is done to) their bodies.

Again, not an unworthy subject — though it also raises a more niche version of a classic film-crit question, one that’s lasted even longer than sex-scene dust-ups on Twitter. In 1973, filmmaker François Truffaut remarked, “Some films claim to be anti-war, but I don’t think I have ever really seen an anti-war film. Every film about war ends up being pro war.” Pleasure makes a case that most films about porn will end up being anti-sex. In that sense, it almost feels like a rebuke to any nascent desire for more sex in American cinema: a seductive argument that business is simply too powerful for pleasure to flourish.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.