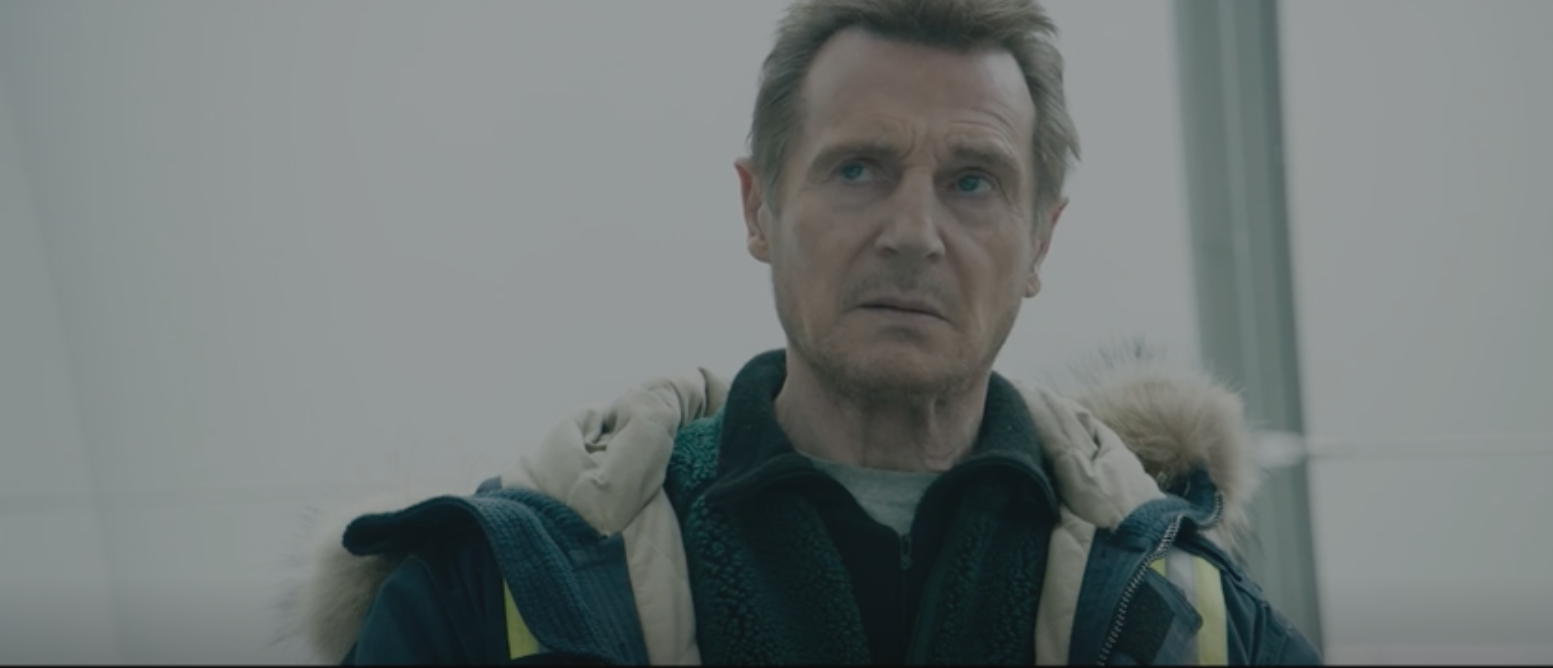

“I’m the bad guy here,” Liam Neeson growls on a phone. As Alex Lewis, a hitman in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, Neeson is adept at portraying the steely menace that made him an action star. In Memory, he ventures into new territory as an actor. Physically frail and forgetful, he’s no longer the most frightening guy in the room.

Until, of course, people realize he’s an unrepentant killer — someone who shoots first, who doesn’t care about collateral damage, who is happy to garrote, slice, burn and explode colleagues.

“You just like Liam, despite the fact that his character is reprehensible,” veteran director Martin Campbell tells InsideHook. “He’s like William Holden in The Wild Bunch. He’s the worst sort of killer and you still love him.”

While Lewis has a moral core of sorts — he won’t kill kids — it’s still surprising to see how dark Neeson will go in pursuit of a role.

“He was a hundred percent willing to go there,” Campbell says. “He’s an actor, right? He doesn’t want to direct, he doesn’t want to produce, none of that. He simply wants to act. And I think he saw this role an opportunity to portray a more complex character, someone with more depth perhaps than what he’s been doing recently.”

Memory is Campbell’s latest feature. Last year he helmed The Protégé with Maggie Q as an international assassin and Michael Keaton as a remorseful hitman pursuing her. Before that, he helped resuscitate a flailing James Bond franchise with Casino Royale.

In 2013, a friend gave Campbell a DVD of The Alzheimer Case / De zaak Alzheimer, a 2003 Belgian film adapted from a novel.

“It was a very good movie, and I loved the idea of a hit man afflicted with Alzheimer’s,” he says. “Also, the complexity of the plot, with its U-turns and surprises. I liked the relationship between Vincent Serra, the Guy Pearce character, and Liam’s hitman. And I really liked the story’s cynical view of law enforcement.”

Pearce plays an unkempt federal agent trying to break up a child sex trafficking ring, only to run up against interference at every turn. A half-hour in, Monica Bellucci turns up as an insanely glamourous El Paso real estate magnate with connections to the mob and a dangerously dissolute son. When Neeson’s character is double-crossed during a contract killing, he sets out for revenge.

Juggling storylines is part of his job as director, according to Campbell. “The thing about directing is that you have to know more about the script than anyone else,” he says. “That’s the secret. I spent a lot of time on this script looking at transitions, what cuts with what, trying to make sure that the different treads of the story all make sense.”

On some level every feature director does that, but Campbell’s films are marked by his quick, focused pacing. Memory was shot in 55 days, with the interiors filmed in a studio in Bulgaria. (Producers adhered to strict COVID policies during the shoot. Anyone caught not wearing a mask was fired.)

“I always shoot efficiently,” he says, almost apologetically. “I rarely ever do a master shot. It’s like the John Ford technique of just cut the clapperboards out and you’ll have the scene.”

So how do you make a film about Alzheimer’s without resorting to melodrama?

“That’s the whole point, isn’t it?” Campbell answers. “Once you get into that, you’re basically in the shit. I remember going to Liam once and saying, ‘I think we’re being a little melodramatic.’ He roared with laughter, saying, ‘Oh, melodrama, I do that really well.’”

Campbell researched Alzheimer’s with an expert, marking each scene where it came into play. Neeson’s character forgets where he left his car keys in an early scene; as the movie progresses, his lapses become more severe. “We were careful not to over-egg the pudding,” the director adds.

Memory boasts an array of weapons and a high body count, especially when Neeson storms a high-rise office building. In fact, guns are an essential part of many of Campbell’s movies. According to the director, so is safety on the set.

“In my experience, there’s always been a system,” he says. “The armorer brings the gun on the set, opens the weapon, pulls out the breach, and shows the actor that it’s empty. Then the armorer says out loud that the weapon is unloaded. That’s been the procedure as far as I can remember. We’ve never deviated from that. I don’t know what happened on the set of Rust [where cinematographer Halyna Hutchins was killed in a shooting on set], but it was tragic. Never, ever in my career have I had a problem with weapons or armorers.”

Although he doesn’t shoot masters, Campbell prepares carefully for every scene, working out blocking on location before rehearsing with the actors.

“I sit there for two or three hours or however long it takes, and I kind of act out the parts,” he explains. “If anyone saw me, I’m sure I would look ridiculous. But that’s how I do it. I plan very specifically the coverage I need. Of course I may overlap two or three lines with some shots, but I know how it’s going to cut before I shoot it.”

In an early scene, Pearce’s Serra and four other cops face off against a trafficker holding a young girl hostage. Campbell builds tension by keeping the camera moving, even when cutting to reverse angles.

“That scene was done very late in the shoot,” he says. “By that time all the actors had bonded. Scenes like that fire them up. They love those sorts of things. So once you’ve positioned them, the main thing is to keep the lid on, just keep it totally real. They all come charging into the room, guns out everywhere, they’re yelling over each other, the trafficker is freaking out.”

Campbell attributes his fast working pace to the years he spent doing TV for the BBC, where he learned shortcuts to deal with tight schedules and limited budgets. Even an extended shootout with complicated stunts that unfolds in a hotel parking garage between Neeson and Mauricio (Lee Boardman), a Mexican hitman, took only two days to shoot.

“If you look at my script for that scene, every shot is listed,” Campbell says. “I went there a day early and figured out every shot. I didn’t storyboard or anything like that, I didn’t have the time. I just sat in the garage for a day and figured out the logic of the scene. That’s when I came up with idea of Mauricio slamming into a car and setting off its alarm. And of course Liam gets to punch the hell out of the guy.”

Neeson was pushing 70 when he made Memory, so Campbell was also aware that he had to limit his stunts appropriately. The actor delivers short bursts of energy, quick slaps and punches, that look extremely persuasive.

“The logic behind action is incredibly important,” Campbell says. “And hopefully it’s connected to the character, so it’s not just mindless action for its own sake, which you see so much today.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.