Is Howard Ratner, the lecherous jeweler in the eye of the cinematic hurricane that is Josh and Benny Safdie’s new film Uncut Gems, good for the Jews? Directors Josh and Benny Safdie kept returning to this question over the long process of conceiving and creating the character with eventual leading man Adam Sandler, his mere presence a powerful image of Jewish iconography. The lion’s share of the film plays out in and around 47th Street in midtown Manhattan, an orthodox enclave termed the Diamond District for its flourishing bling trade. It’s also a bustling hub of Semitic history and heritage, a physical space where Jews continue to negotiate age-old prejudices and forge ahead into a cross-cultural future.

“If you go back to Middle Ages, the Jewish people were given the thing that nobody wanted to do, which was working with money,” Josh Safdie explains to InsideHook at the offices of distributor A24, just a brief schlep from the film’s shooting locations 20 blocks northeast. “The church saw capitalism as a threat, a dirty business, so why not let the Jews do it? They ended up using the only thing they had access to as their point of integration. In the Diamond District in particular, the materialist culture perpetuates the idea that through consumerism and the acquiring of riches, you can transcend bigotries and discrimination. Money’s the bridge.”

The almighty dollar looms large in both Howard’s life and the story of the Jewish people. It’s the first stereotype anti-Semites go to when playing dirty: the covetous penny-pincher, rubbing his hands together as he counts his shekels. As a gambling addict obsessed with maintaining his precarious balance of bets and debts — someone whose life literally depends on the numbers in his bank account — Howard would seem to play into that perception. And as an incorrigible horndog with a fetching shiksa girlfriend on the side, doubly so. But the Safdie boys wanted Howard to be something closer to a “prideful kabuki version” of a Jewish caricature, someone who could “wear the stereotypes as a badge of honor, then barge right through them.”

“Howard is what happens when a person goes into an industry fueled by consumerism,” Benny says. “You’re taking a calcified version of the place that Jews were put in, and seeing how it’s formed over centuries.” In other words, he is as capitalism made him, a figure vilified for being too good at the game he was forced to play. Cash served as a field-leveler, and one that he could work to his advantage. “Everyone’s equal in Howard’s showroom, as long as they’ve got the money. If you’re paying, everyone’s the same to him. He’ll give everybody a moment, even the guy delivering packages. He knows everyone, knows how to make stuff happen; he’s what’s referred to in Yiddish as a macher.”

For inspiration, the co-directors looked to indie magazine pioneer and career subversive Al Goldstein, founder of Screw magazine, in whom they saw “a spiritualism in consumerism.” They were moved by his rants from his long-running public access show Midnight Blue against such foes as Trans World Airlines or cheap-o luggage manufacturers. “He could be triggered by one of these objects into talking about what it means to love your wife, and love yourself,” Josh says. “That’s very Howard: this manic person spouting about stuff, who can then become very loving in another second.”

Their other point of reference was their own father, another deeply flawed larger-than-life personality who worked in the Diamond District. He’d regale his boys with tall tales of the dealers and clients with whom he’d do business, and in them, they saw an opening to a world adjacent to their own. “Our dad would bring jewelry to areas where the only non-black residents were the other Jewish jewelers,” Benny says.

Josh jumps right in, a fraternal rapport that sounds to the untrained ear like talking over each other: “He was telling us about this jeweler who had a recording booth in the back of his store, on Pitkin Avenue in East New York. Aspiring rappers would come in to buy jewelry, and behind a shelf of gold chains, they could cut a record. This was its own tiny enterprise, with the owner helping to get the attention of people in the industry, and you still see stuff like this in the Diamond District now. When we were there, we met so many rappers who had come with the purpose of getting a statement piece and implicitly announcing themselves. The jewelers take anyone with cash, but with some rappers, they’ll cut a deal and rise together. Exposure both ways.”

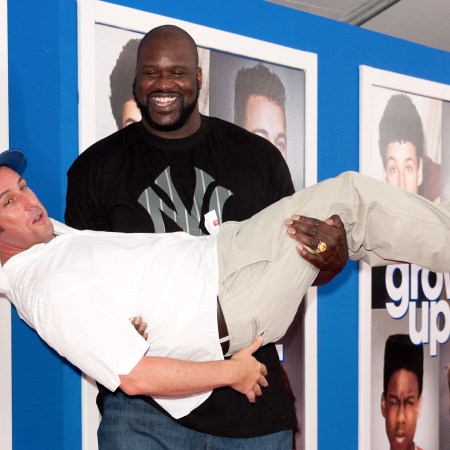

Starting with the prelude that opens on black Jews working in the opal mines of Ethiopia, the intersection of the Jewish and African-American communities emerges as the thematic crux of the film. One particularly precious stone harvested from the area supplies the film with its MacGuffin, as well as a canny physical symbol of the nexus between Howard’s domain and the hip-hop scene, in which he can only hover around the fringes. Notwithstanding the cultural gap between Howard and his predominantly black clientele — former Boston Celtics all-star Kevin Garnett, playing himself, notably among them — their collaboration seeds a precarious mutual respect. There’s an age-old pathology at play here, one intuitively understood by every reedy Jewish 13-year-old somehow able to find himself in the canon of rap.

“If you look up the general connection between the Jews and the black community, it’s something of an ineffable bond,” Josh says. “Both cultures experienced slavery, oppression — of course, farther in the rearview for Jewish culture than African-American, but there’s some shared ground there. In the history of America, during the Civil Rights movement, a lot of Jewish activists took part because they felt a need to stand up in solidarity. One of the founders of the NAACP was a Jew! The connection is there, but it’s a complicated one, built around the sensation of being an other shut out from some sectors of society.”

The script makes passing mention of the fact that Howard was the first jeweler to ink contracts with recording artists for music videos. In an eerily perfect unison, the Safdies both describe him as “a sort of self-fashioned ambassador” to the hip-hop community, right down to the retouched photos lining his walls, in which Sandler’s face takes the place of Diamond District hotshot Izzy Avianne’s. The A-list superstar clicked right into the scuzzy low-rent milieu the Safdies call home, due in no small part to his innate handle on the particulars of Jewish culture.

A few weeks earlier, a radio DJ in Austin showed the brothers a photo of his old Little League team and pointed out, “Look, that’s me and that’s Adam Sandler, the only Jews in all of New Hampshire.” Sandler grew up as one of a small number of kids that celebrated Hanukkah in his town, and tapped into his identity by wearing out the grooves on Borscht Belt comedy records. “We think of him as the modern Jerry Lewis, in that he always is Adam Sandler in these roles, this vessel-character, and his movies are films with situational humor,” Benny says.

An integral part of the “Adam Sandler” that informs his every appearance is his Judaism, a set of dramatic and comedic instincts that take over in the scene that finds Howard at an unusually tense Passover seder. (His brother-in-law wants to break his legs over some outstanding IOUs. Long story.) There’s a lived-in specificity to the tableau of an after-dinner schluff, as rambunctious kids run around in search of the afikoman while the grown-ups smoke stogies and argue about basketball. Look close and you’ll see a certain affection for this outer-borough, upper-middle-class faction of the tribe, which sets the film’s deconstructions of tired old tropes apart from simply playing them straight.

To wit, there’s the dichotomy between Howard’s aforementioned non-Jewish girlfriend Julia (Julia Fox) and his stern, take-no-guff wife Dinah (Idina Menzel). From a distance, their broad contours cast them as objects of desire for the masculine Jewish psyche: in the one corner, a younger, sexed-up good-time gal all the more desirable for being forbidden by Talmudic dictates, in the other an icy shrew. But they both reveal themselves to contain much more than can be perceived at first glance.

“In this case, Idina’s character is the one person who’s not falling for Howard’s shit,” Josh says. “To be ‘shrewish’ would mean that he’s not doing anything wrong, and he’s done everything wrong! She’s reacting as any reasonable person would react … She says that he’s the most annoying person she’s ever met. She’s where the buck stops. As for Julia’s character, we also wanted to make her more than the side girlfriend. She always keeps you guessing. She uses the perception of her to get what she needs and come out on top. She’s capable, resourceful, good on her feet. Plus, the love between her and Howard runs a bit truer and deeper than you’d initially think.”

Though shot through with some good old-fashioned Hebrew self-loathing — the film is primarily concerned with Howard’s assorted failings as a husband and less-than-righteous man — Uncut Gems sees the modern Jew in detail too fine to be crass or reductive. The Safdies love Howard in spite of all that is contemptible about him, a contradiction that comes as second nature to a religion orienting all of its holidays around remembering hardship. The bitter edge to all Jewish rejoicing, the constant awareness of all the injustice of the past and present, forms the central pillar around which Howard was built. Good for the Jews, bad for the Jews — he is the Jews. Josh sees him as an avatar for hundreds of years of Judaic tradition, in all its strife and resilience. “It’s about learning through suffering,” he says, “carrying the burdens of the past, and using them to your advantage.” Whether he’s referring to his film or the religion coursing through it remains unclear.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.