It’s generally an ill omen when a movie starts by defining itself on the grounds of what it isn’t rather than what it is. A rambling voiceover preamble that details a well-trod genre of story and then turns around to declare with an invisible smugness that “this is not that kind of story” foretells a blunt-force deconstruction that calls too much attention to its own cleverness.

Fortunately, David Lowery’s new film The Green Knight is not that kind of “not that kind of story” story.

His screen retelling of the 14th-century Middle English fable of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight opens in portentous fashion, with a halo-looking crown drifting in defiance of gravity down onto the waiting head of Dev Patel, which then bursts into flame in the first of what will be multiple spontaneous combustions. Overlaid on this regal tableau, a narrator informs us in grandiloquent antiquated language that those expecting a medieval epic in keeping with the gallant exploits of Arthurian legend have another thing coming. The narrator’s words don’t just serve as ornate place-setting in the oral tradition, but as a preemptive disclaimer from Lowery anticipating the caliber of reaction that results in F Cinemascores. The most audacious film of his career — which is saying something for a guy who’s already marshaled $65 million for the one good live-action remake of a Disney classic — eschews the swordplay, maiden-rescuing and beast-slaying identified with this lineage of fiction. The giants teased in the deftly misleading trailer appear for all of 10 seconds, don’t do much of anything, then saunter away. The warning hasn’t been issued idly; every facet of this revision aims for atypicality, from the ethereal look to the weightier heaven on Lowery’s mind.

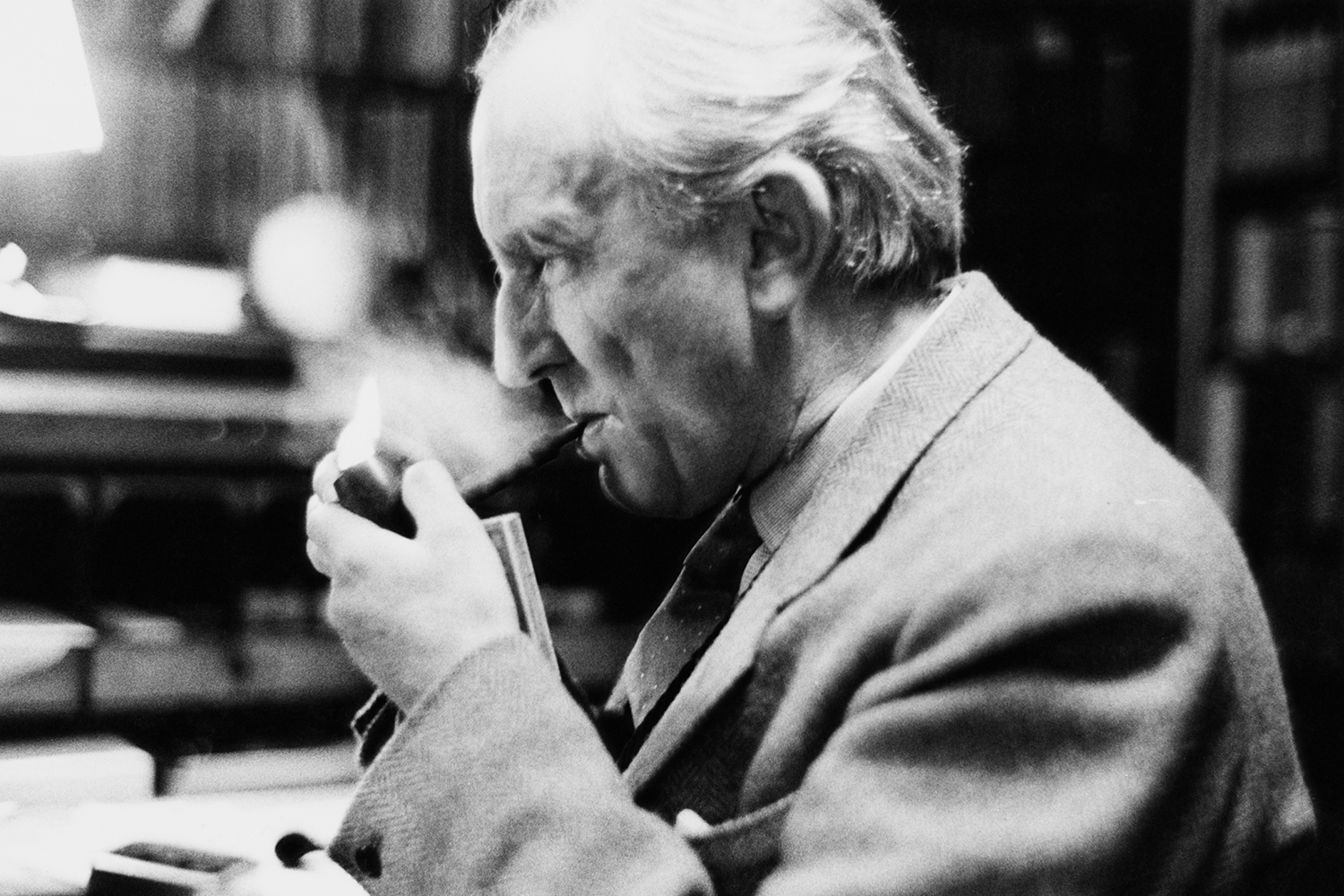

Some of the open spaces left by all that’s been excised stay that way, Gawain’s quest through the primordial English wilds marked by a sense of roominess. Ireland stands in for some stretches, the location shooting rivaling that of Lord of the Rings, a comparison Lowery most likely invites in light of Tolkien being the most noted translator of the poem’s verse. As he demonstrated in Pete’s Dragon, the director feels more comfortable basking in the majesty of nature than most working at this budget or scale, unafraid to put his loose and discursive plot on hold so we can take in the scenery. Depicted as a fertile sprawl under an opalescent sky, the countryside represents a porous membrane between the mortal and mystical planes, hints of fantasy gleaming through here and there. Aggressive color-grading in orange or grey, so often abused for atmosphere clashing with more earthbound concepts, befits the otherworldly aura cultivated here.

In the more active legs of Gawain’s odyssey, the unexpected, strange and wondrous give shape to his path. Along the way, he makes the acquaintance of an untrustworthy bandit (Barry Keoghan) and an equally suspicious Lord (Joel Edgerton), forces of opposition to complement the distracting affections of the house’s Lady (Alicia Vikander) and the gossamery Saint Winifred (Erin Kellyman). These figures tend to send Gawain from one phase of his journey to the next, acting upon him rather than responding to his actions. In tales of knights errant, it’s de rigueur that the protagonist should encounter tertiary tasks and get temporarily sidetracked, but being guided by external parties casts Gawain in a more passive light than his forebears. The character is introduced to us as an everyman corrective to the stock hero type, less as an antihero and more like a nonhero. He’s contented with his rapscallion lifestyle, between the steins of mead and the romps with his paramour Esel (also Vikander, a significant formal rhyme), if hungry for glory.

That’s what compels him to behave rashly when the tree-entity known as the Green Knight enters Arthur’s court and makes an offer: any man may land a blow upon his wooden body without resistance, in the knowledge that “one year hence,” they must travel to his Green Chapel and receive the same strikes they doled out. One beheading later, Gawain has sealed his fate, though that doesn’t stop him from soaking up the public admiration over the condensed 12 months that follow. In one of a handful of tricks shrinking and elongating time, Lowery represents this year with illustrations upon a spinning wheel, invoking the goddess Fortuna and raising the question of destiny yet again. With the clock ticking, Gawain sets a course for the Green Knight’s mossy lair in the hopes of proving to himself that he’s the embodiment of valor everyone else already believes he is, a self-deception that will ultimately be his undoing.

He can lie to everyone else about his deep-seated unsureness, but he can’t lie to himself, and that distinction will be crucial once zero hour rolls around. The film frames Gawain’s required offering to the Knight as a Christly sacrifice, a compact that must be fulfilled spiritually as well as physically, a giving of the body reinforced by a surrender of the mind to a higher authority. That’s more than he can muster, however; when the face-off finally arrives, Gawain flinches and ultimately balks at the pound of flesh owed to the Earth’s living embodiment. (Here’s where we begin to enter spoiler territory, to whatever extent a film so dependent on visual execution — pun intended — over writing can be ruined by outlining the plot.) He retreats and perverts the historical record, the years flashing by as he takes a queen, leaves Esel behind, and grows old in a timeline that wasn’t meant to be. Then, in a move cribbed from Scorsese’s take on The Last Temptation of Christ, the narrative slingshots back to the moment before Gawain backed out to reveal everything we’ve seen since then as a projection or dream.

Lowery’s most decisive departure from the original text steers it toward his own filmography, in which he has cultivated a looser, liberated relationship to the passage of the ages. His polarizing A Ghost Story would flit forward and back through decades in a single cut to chart the lasting presence of a dead man in the house he called home, trading linear progression for a circular structure. In that film, the musician Will Oldham pops up smack-dab in the middle to explain the core theme of people’s influence lingering long after they pass away, a notion Lowery revisits and integrates more foundationally into his latest work. Gawain fosters an almost vain preoccupation with his legacy, both conflated with and contrasted against his entry to a higher afterlife. Edgerton’s character asks Gawain why he’s taking on the Green Knight in the first place, to which the younger man can only reply that he’s doing what a hero would do, a tautology revealing his cart-before-horse mentality about achieving greatness. He’ll take much longer to learn that heaven is earned not by deeds alone, but by the contents of the soul.

Earlier this year, I wrote about John Boorman’s Excalibur and pled for a return to his unorthodox model of the knights-and-armor subgenre: rife with incestuous deception and adult sexuality, lush beyond all imagination, conflicted about the heroism others might take at face value. I couldn’t have imagined how swiftly and comprehensively my wishes would be answered by Lowery and his keen-eyed perspectives on the falsehoods interwoven into our mythmaking. The Green Knight commandeers a blockbuster-sized scope for a more accomplished breed of summer-season adventure, literary in its ambitions and restless in its cinematic flourishes. Crafted with a curious philosophical streak and an eye for the magnificent, it looms over everything else currently in theaters like one of the giants crossing Gawain’s trail, every bit as serene and calmly self-assured.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.