What was Stephen Bremner doing contacting the company’s long-since-retired employees? Why did he want to look at the fragments of dusty documents from a building that had been demolished in 2003, with the land given over to a housing complex? Why did he have analysts ready to prove some wild hunch?

It’s not often that the whisky industry conjures up a detective story, but Bremner knew he was on to something. He had been working for the Japanese distillery company Takara Shuzo for 20 years — he’s now managing director of its Scotch whisky subsidiary Tomatin Distillery Co — and had grown increasingly curious about its Shirakawa distillery. Located in the Fukushima Prefecture some 200 km north of Tokyo, Shirakawa was a pioneer of malt whisky making in Japan. Those whisky days were long gone, but it made whisky for 20 years (between 1951 and 1969) before switching to the production of other spirits. Might, indeed, there be any stock from that time still around?

“I came to hear about how they’d once had this malt whisky distillery in Shirakawa. So I’d ask, ‘Is there any stock left over?’ And I’d always get a sketchy answer,” Bremner explains. “In part, that was because Takara Shuzu is a really big company, and, in part, because the guys I’d ask likely would [for cultural reasons] never put the question further up the food chain. So I’d just get a ‘no, we don’t think so’ answer all the time.”

That is until his digging led him to have another conversation with a Japanese colleague. He told him that there were rumors of a last parcel of stock. But then said colleague got moved to a U.S. subsidiary. So Bremner tracked down a couple of ex-employees who had worked at Shirakawa in the 1980s. Again, they said they’d heard of this parcel. The demolishing of the distillery meant that many of the historical records had been lost, but some survived, and these — regarding production in the 1950s — were uncovered.

“We just started to put together all these small pieces of information — the type of barley that would have been used then, the type of casks, and slowly this information gave us the clarity we needed to convince us that this parcel really did exist,” he says. Small wonder that some in the whisky industry made the joke that he was their Indiana Jones, the adventurer archaeologist of alcohol. (“But unfortunately I’m not that cool,” says Bremner.)

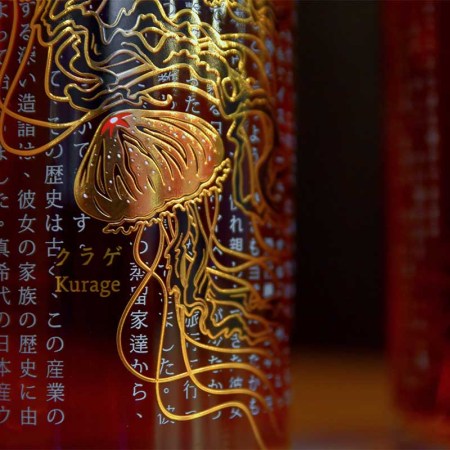

Picture the closing scenes of Raiders of the Lost Ark, when the Ark of the Covenant is being tucked away among millions of anonymous crates. That was sort of the case in 2019, when in the corner of a vast warehouse in the Miyazaki Prefecture — at the other end of the country — some anonymous stainless steel vats were uncovered. And they, too, were full of something very special: the oldest and rarest Japanese single malt, just 1,500 bottles of it, now available for an eye-watering $29,000 each. Still, collectors and investors are lining up.

With a Japanese Whisky Shortage Nigh, It's Time to Start Investing

We spoke with experts to figure out which bottles you should stock up on ASAPThat Japanese whisky might command so much may be surprising to anyone who didn’t know Japan has a history of making whisky at all. But production began before World War II, picked up during it and, while the quality was far from world-class to start with, it found growing popularity during the U.S. post-war occupation. The domestic market kept growing until its high point in 1984 when the drink industry’s radical shift from brown to white spirits — vodka and gin, notably — persuaded many manufacturers to shift production to shochu, a traditional Japanese white spirit distilled typically using sweet potato.

At the time, shochu was regarded as a cheap and rough drink. Takara Shuzo would reinvent it as an upscale one, called Jun, in part through a marketing campaign involving David Bowie and John Travolta, in part by being the first company to mature shochu by putting it, just like whisky, in casks for some time.

“It’s easy in retrospect to say there was this huge lost opportunity when Japanese spirits companies moved away from whisky when they made such a great success of shochu,” says Japanese whisky expert Stefan van Eycken. Indeed, it’s what makes this remarkable Shirakawa discovery so special: It dates to 1958, making this bottling the earliest known single vintage (that is, from one single year) from a Japanese distillery.

“What’s more, 1958 seems to have been the year when Japanese production really went high quality — their own yeasts, domestic not imported barley, copper pot stills, Japanese mask casks,” van Eycken adds. “You wouldn’t be able to replicate that today easily. It’s like a snapshot of a crucial moment in Japanese whisky making when it upped its game. If the Shirakawa had been in 1957, it might have been a whole other story. When I was told the story, my jaw dropped.”

The excitement to whisky nerds further lies in the fact that Shirakawa produced whisky only for blending, notably for its Takara Shuzo’s flagship King brand — it never, officially, produced a single malt bottling. So this is the last remaining parcel of that single malt — making it, as it were, the first and only official single malt from the Japanese distillery.

Indeed, the Shirakawa release comes as Japanese whisky continues its ascendance, both in quality and in quantity. Now there are more than 40 small active craft whisky distilleries in Japan, with many more in the planning stages to meet new demand and provide more variety.

“The best of the best whisky turned out to be Japanese, and hardcore whisky enthusiasts started to buy it,” van Eycken says. “And, as with music or art, with that validation abroad, the Japanese bought into it [more enthusiastically]. That’s when the tide started turning. “Now it’s actually very hard to buy Japanese whisky because there’s not enough of it to go around.”

“But of course, the point is that all of those whiskies are also very young,” he adds. “And that brings us to the appeal of this Shirakawa release. If someone had told me that a single malt Japanese whisky from the late ‘50s would be released, I’d have told them to keep dreaming. Single malt as a category didn’t even really exist in Japan until the mid-80s.”

Bremner still has questions he will never be able to answer. Just how many years did this single malt send in the cask, for example? And, while independent analysis has proven that the liquid is a single malt, made using Japanese malted barley and Mizunara oak, and that it’s had at least decades of cask maturation, the precise production method will remain forever a mystery.

But at least he’s had luck on his side. As van Eycken and Bremner both stress, as rare as this whisky is, it may still have tasted awful. After all, for decades it’s been stored in stainless steel vats of the kind used for shochu, which do nothing to help remove impurities from whisky. Van Eycken points out that while distilleries in Scotland have a culture of swapping stock — so there are all these parcels circulating and a deep knowledge of older stock builds up — no one sells stock to third parties in Japan.

“Given its age for a Japanese whisky, no one until now had any idea what something like this would taste like,” he enthuses. “In fact, it’s still hard to imagine the possibility of ever tasting something like this.”

And the result? “I have to say that when I first went to taste it, I was slightly nervous,” Bremner recalls. “And I think the owners of the distillery were nervous about letting me taste it, too, because even in their eyes, Scotch is still at the top of the whisky category. But when I tasted it I was blown away. If this Shirakawa 1958 whisky was a top single malt from Scotland, the only reaction would be ‘Wow!’ They [the parent company] just had no idea what they had. They had no idea how significant it was. And before you ask, we’ve looked, and there isn’t any more of it.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.