“I couldn’t wait to get my first motorbike, and in those days the world was worried about running out of oil, so I thought, If I ever get my license, I’m going to have to make my own fuel, by distilling ethanol,” recalls Paddy Lowe. “Jumping to now, it’s a different problem, but if I think back through my 40-plus years in motoring I’ve always had this sense of consuming something finite, that here’s this fuel that’s taken millions of years to make and I’m burning it up.”

Today, Lowe might be considered a poacher turned gamekeeper. As the one-time chief technical officer for the Formula 1 teams of McLaren, Williams and Mercedes, he was charged with helping to make race cars go faster, arguably whatever the environmental cost. Now he’s the co-founder, with professor Nilay Shah of Imperial College London, of Zero Petroleum, a company hoping to offer the world a carbon-neutral synthetic fuel that’s a replacement for fossil fuels. As he puts it in his elevator pitch, he’s hoping it’s a part of “a complete transformation of world energy.”

“This is, we argue, really an extraordinary, transformative moment away from our addiction to fossil petroleum,” Lowe says, “not just for energy but with plastics, textiles, pharmaceuticals.”

Why the big statement? Because Zero Petroleum recently unveiled what it says is the world’s first fully sustainable fuel. It’s not a biofuel, “which to my mind is a bit of a misnomer,” says Lowe, “because they’re not really bio at all, they’re not fossil-free if you track back through their production process, and they’re very hard to scale.” Rather Zero Petroleum has taken a century-old idea — the Fischer-Tropsch process, developed by chemists Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch in 1925 — and given it an overhaul.

Zero Petroleum’s proprietary, and somewhat secret, process means processing hydrogen (extracted from water by electrolysis using renewable electricity) together with carbon (taken from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by direct air capture) to produce a synthetic fuel. What’s more, this fuel doesn’t need refinery upgrading. It can go straight into your combustion-engined car as is, the emissions then produced by burning it equal to those that go into making it.

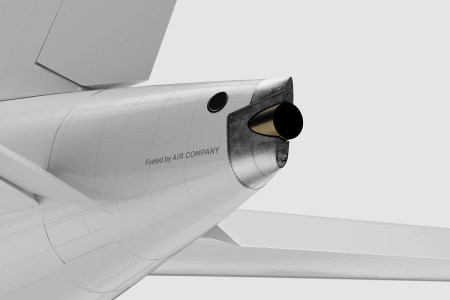

If that sounds like the kind of chemistry that works in a lab, but not in the real world, think again. In late 2021, Zero Petroleum won a Guinness World Record by using its fuel to power an aircraft, the first use of a synthetic fuel in aviation history, a feat considered so important that London’s Science Museum acquired some materials from that event for permanent exhibition. Then there’s the U.K.’s Royal Air Force, which was a partner in the record attempt and has now signed up Zero Petroleum to supply all of its aviation fuel needs in its bid to go carbon neutral by 2040.

Lowe’s company has also recently opened a development lab in Bicester, in the U.K., and is now pulling together the finance — ex-F1 champ Damon Hill is one investor — to open its first commercial production plant, probably in the U.K., with a number of plants in the U.S. and Japan ideally set to follow. Small wonder that Lowe is happy calling his product “a game-changer.”

“I thoroughly enjoyed my career in Formula 1, and we did all joke that one day we’d get a proper job, because it never felt like work. But I feel that this is a proper job now, and the most rewarding too,” he adds. “[For me], the idea of making synthetic fuels isn’t just about meeting environmental objectives, it’s about the liberation it provides in terms of still being able to do what you enjoy, as well as doing your duty. It’s enjoyment without guilt.”

This Tiny Brooklyn Company Is About to Upend the Aviation Industry

Air Company creates products like vodka and perfume from captured CO2. Now, their tech is being used to create sustainable jet fuel.That’s why petrolheads the world over might well be celebrating. Zero Petroleum has already demonstrated the efficacy of its fuel in two supercars. As Lowe explains, while he doesn’t see his synthetic fuel as an alternative to electric cars — they are the future, he stresses — it will at least provide a future for racing and vintage cars, albeit likely at a higher price than you’d pay for unleaded gasoline at the pump (right now, the target sale price for 2027 is £3 per liter, or about $11 a gallon). That is, until some form of carbon pricing comes in for fossil fuels to account for the externalities of burning them. What’s more, Zero Petroleum’s fuel will likewise work for what he calls “legacy” cars, those millions of combustion-engined vehicles that will still be on the road for the next 20 or 30 years, and which it would, it’s argued, be environmentally unsound to simply scrap.

However, Lowe explains, synthetic fuels are most important not because they’ll allow you to keep your beloved jalopy going; rather, it’s the fact that the development of synthetic fuels is effectively mandated because, given current technology, electrification of any mode of transport much larger than a car — for which the power-to-weight ratio makes an electric powertrain work out just fine — is a non-starter. For example, an airliner would require a battery some 50 times heavier than an internal combustion engine.

It’s not just aviation — which, given its contribution to global emissions, is seeing the drive towards Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) — or defense, which, as Loewe points out, almost by definition needs a reliable, nationally-controlled fuel supply. “You can’t run an air force on waste hamburgers,” he laughs. It’s agriculture, trains and shipping too. “Any type of fuel you need — whether that’s for a Typhoon fighter jet or for a combine harvester — it’s just a variation of the same process,” he explains. What is arguably needed now is something like the CO2 reduction target imposed on cars — which has helped drive the uptake in electric vehicles — to likewise be applied to vehicles like airplanes and cargo ships.

This all means we’re theoretically going to need a lot of this new synthetic fuel. That’s why Lowe isn’t concerned about the likes of Porsche/Siemens or the Saudi oil giant Aramco, among other players, which are now piloting their own synthetic fuel projects, some of which make use of landfill waste. “That’s not competition,” he argues, “but affirmation that this is the right direction [for energy production]. The bottom line is that there’s room for a lot of players in this new market, just as oil and gas, although very mature, has a very wide range of companies too.” Maybe he just wants to get their first, with the most efficient product.

Can Zero Petroleum’s synthetic fuel be scaled up to meet the demand you get from a global economy dependent on moving stuff, and people, around the world? Lowe concedes that there are hurdles to making the company’s fuel fully sustainable. It could use an outside source of green hydrogen but, he says, hydrogen is notoriously hard to contain and transport — its molecule is so small that it will leach through steel. That would mean building Zero Petroleum’s production facilities near green hydrogen plants; it’s not impossible, but not ideal in terms of reaching the most thirsty markets. He would rather Zero produce its own green hydrogen. Then the problem becomes the supply of renewable electricity.

“With what we’re doing with this synthetic fuel, the feedstock — air and water — is effectively infinite. In theory there’s no limit to scale,” he notes. “So the challenge really is the rate at which the world can build out renewable energy [to power the process]. But of course [Zero Petroleum aside] there’s no escape from that challenge anyway if we want to stop using energy dug up from the ground. In the long term I think we’ll see fusion come into play. That’s the holy grail of renewable energy.”

Lowe is, he knows, edging more into the distant future of energy supply with that hope. As the joke goes, fusion energy is 30 years away, and always will be (though with the recent breakthrough at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, things are finally looking up on that front). But in the meantime, maybe he could claim to have brought his own holy grail into being. We shall see.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.