Betty Dodson’s office is in her bedroom. This seems appropriate. Metaphorically, it’s where she’s conducted her work her whole life—although she insists that literally, the living room gets that distinction. “It was nothing about the bed,” she says. “Nobody gets in my bed but me. It was all about the living room and having a group.” This goes for her “Bodysex” workshops, a mainstay of ‘70s feminist circles she revived in 2013, and the storied sex parties she held here, in the rent-controlled midtown Manhattan condo, she’s lived in for half a century.

Dodson surveys the spacious living room “I had a lot of parties here,” she says. “We’d push the furniture against the wall. I had two double beds side by side and a little couch. The sex was taking place in the back room. I’d have coffee, cookies, cheese, crackers. They’d be socializing. And then somebody might be f*cking over by the fireplace.” This doesn’t strike her as unusual. “It was just a natural way to socialize,” she shrugs. “It wasn’t a big f*ckin’ deal, like it is now.”

Meet Betty Dodson—88-year-old sex educator, author, female masturbation coach, indomitable crusader for sex-positivity, and not your average octogenarian. (Does your grandmother have four dildos on her night table? Does your grandmother have any dildos on her night table?) Dodson has wispy gray hair, a sailor’s mouth, and the bearing and diction of a woman 20 years her junior. She drinks (“at cocktail hour”), smokes a cigarette or two a day, and has a taste for marijuana, but attributes her appearance and relative sprightliness to a healthful diet. And regular orgasms.

Hitachi Magic Wand Massager. (Marston)

Sex—in all its vexed, stigmatic permutations—has been Dodson’s life’s work. In 1965, 35 years old and fresh off a failed and sexually unsatisfying marriage, she embraced the free love movement that was central to the burgeoning sexual revolution. She also began to develop a theory of masturbation as being the basis of all human sexual activity, and the foundation for what she calls “partnersex.” (The word, apparently of Dodson’s coining, is known to most by its more familiar name, “sex”—but when your writings and practice focus so heavily on masturbation, the distinction helps.)

While Dodson initially cottoned to the consciousness-raising feminism of the late ’60s and early ’70s, she soon grew disenchanted with what she regarded as the movement’s swift devolution into “women complaining about men” and its anti-sexual stance. (She writes in her memoir that her sex-positive panegyrics at CR meetings were met with resentful silence from women who unanimously considered sex a private matter.) Her solution? “Sexual consciousness-raising. Learning about our bodies, our sexuality.”

She’d shown some girlfriends masturbation techniques after beginning to suspect they were faking orgasms at her parties, and before long was hosting embryonic versions of her Bodysex workshops—groups of 10-15 women, sitting in a circle in her living room, exploring their bodies, overcoming genital shame, and learning, with Dodson’s guidance, how to masturbate to orgasm. (The workshops got a loving shout-out in a recent episode of Comedy Central’s Broad City, where lead character Ilana attends a private masturbation session with a grandmotherly teacher named Betty. Dodson’s memoir can be spotted on the set, and her erotic art dots the walls.)

But Dodson found mainstream feminist channels priggish and largely unsympathetic to her crusade. In 1972, Ms. magazine commissioned her to write a piece on female masturbation, only to balk after seeing the result—Dodson contends the 18-page article was too radical. (She writes that Gloria Steinem personally instructed her to remove all the four-letter words from an early draft.) The piece would become her self-published 1974 book, Liberating Masturbation: A Meditation on Self-Love, and Ms. would eventually publish an abridged version.

Dodson eventually found acceptance with her presentations at the 1973 Women’s Sexuality Conference hosted by the National Organization for Women. On the first day, Dodson delivered a barn-burning speech detailing her recent sexual explorations, including her forays into lesbianism and her use of a vibrator. (She sold samples afterward and has been credited with re-introducing the device to women.) On day two, she projected a slideshow of vulvas, rhapsodizing about their beauty and variety. The crowd reaction evolved from hostile (at her casual use of the word “c*nt”) to spellbound to rapturous. She walked off to a standing ovation.

It had been a long time in the making. Dodson started down the road of sexual exploration early, with help from an unlikely source. “I had a great mother,” she says, her fondness palpable. “She had no religion, no education, and no mother. She was raised by her sisters on a farm.” For Dodson’s mother, bodily functions—be they sexual or excretory—”were all natural. She thought masturbation was natural for kids—because she did it, and didn’t have a mother to tell her not to.”

At 20, Dodson moved to Manhattan to study art and work as a freelance commercial illustrator. In her decade as a comely, unattached art student, being sexual “was a struggle, because it wasn’t fashionable. Everyone was paired off. So people saw me as a loose woman. My friends back in Wichita thought I was surely a prostitute.” (She freely acknowledges that she was “giving it all away.”) An unhappy marriage to a man named Fred Stern followed, and their divorce auspiciously coincided with the dawn of the high ‘60s.

The white picket fence dream never appealed. “I knew that wasn’t what I wanted,” says Dodson. “I didn’t want to have a family. I didn’t want to raise kids. I saw what my mother went through—talk about unrewarding.” She was, and remains, similarly unenthusiastic about monogamy. “Do you know that there are some people that have only had sex with each other for 50 years? And they think that’s a success story. I think it’s a tragedy.”

An emotionally fulfilling, sexually satisfying, long-term monogamous relationship is “wonderful,” she concedes—”but it’d be boring. How do you want to live? Do you want to have one person and settle down and be in this little box? Or do you want to experience the world first? And after you settle down, you can make arrangements—honey, why don’t we date other people? But do it fairly discreetly and with dignity, instead of lying and cheating.”

She recounts a non-exclusive 40-year relationship with Grant Taylor, a former NYU English professor, and its initial complications. “I’m not saying it’s easy in the beginning,” she says. “You gotta deal with possessive feelings, jealousy. But if you can get there, and have that kind of trust—it’s freedom.” She lowers her voice to a confidential whisper. “People are terrified of freedom. We want rules.”

It quickly becomes clear that Dodson, like her freethinking mother, regards rules and societal norms as mere suggestions. Her views on sleeping arrangements are typically heterodox. “There is no way I could imagine sleeping with anyone in my bed,” she says, “no matter how crazy in love I was, no matter what phenomenal orgasms I got. I sleep alone. This thing of sleeping with someone is so sick—it’s like you have to have a teddy bear.” She clarifies that while she will have sex in bed, it’s far from the only option—hence the fuzzy wall-to-wall carpeting, the benefits of which compensate for occasional rug-burned elbows.

There is also her mouth. If you consider frank discussion of sex indecorous, time spent with Dodson can leave you reeling—and reconsidering. In her hands, even the dirtiest stories and filthiest fantasies are recounted with love—she speaks of former partners fondly and past liaisons wistfully. At the crudest and most degrading pole of the sex talk spectrum is the “locker-room talk,” unrepentantly practiced by a certain recently promoted former reality TV star; at its most elevated, as demonstrated by Dodson, frank talk of the joy derived from one’s sexuality is as natural and unremarkable as discussion of art, food, the weather. The topic under review is pleasure: what is there to be embarrassed about?

It may depend on whom you ask. Dodson’s earthy and forthright manner has cost her exposure over the years, an exclusion that rankles—to a point. “I think the idea of organic growth makes sense,” she says. “Because if I had too much exposure in the ‘80s, I wouldn’t be here—someone would’ve shot me. You can’t go around talking like I talk, publically.” As for corporate media bigwigs, “those guys are terrified of me. I’m a pariah, like Medusa with the snakes.” She affects a conspiratorial growl. “Vibrators, vibrators…we don’t need you guys anymore…we’re having orgasms out our ears!”

This fraught relationship with the mainstream has pervaded Dodson’s life and work. Why, for instance, was it feisty sex expert Dr. Ruth Westheimer and not Dodson who was the darling of the ‘80s talk show circuit? Dodson bristles. ”The culture cannot handle the truth. Dr. Ruth is a fantasy. Dr. Ruth is your grandmother with a funny accent that you laugh at—you never listen to what she says. She did not make an impact. I have.”

She reserves similar contempt for Jocelyn Elders, the U.S. Surgeon General who was forced to resign in 1994 after saying of masturbation, “I think that it is part of human sexuality, and perhaps it should be taught,” thereby gaining some measure of heroism in certain circles. “Jocelyn Elders didn’t do sh*t.” Some venom now. “She said the word ‘masturbation,’ and I hate that she’s getting all the credit. I’ve been teaching it a lifetime. And nobody wants to talk about that.”

Considering Dodson’s decades-long track record, her resentment isn’t unreasonable. But for all her ire, she and Elders are largely on the same page. “We should teach people how to masturbate,” she says, outlining her ideal Sex Ed syllabus. “First, we could let kids know that it’s okay to touch themselves, and that their sex organs are beautiful and different. We could teach different methods of masturbating. I mean, it’s A-B-C.”

Okay—maybe your local school board won’t be adopting this program anytime soon. But Dodson isn���t deterred. She wants for younger generations things she didn’t have and delights in their getting them. Her eyes widen with wonder as she learns the concept of dating apps—apparently, it’s the first she’s heard of them. “Wow,” she whispers, awed. She marvels at the idea of rifling through potential partners like playing cards, and of couples meeting in person after an electronic correspondence. “Do they have sex?” That’s the idea. “I can’t imagine—that’s very convenient. I never would’ve gotten any work done.”

Where many feminists feel vindication in the #MeToo moment, Dodson is ambivalent. She says that the accusers are “doing the best they can,” but bemoans the lack of “success stories.” She supplies one, a table-turning anecdote from her art school days where tired of leering men in Garment District showrooms, she would stare intently at their crotches. “They would get very nervous. It worked like a f*ckin’ dream.” For foiling unwanted advances, “there are so many tricks you can pull to bail yourself out”—she suggests feigning retching—”but we’re not told.”

For Dodson, the prevailing focus on sexual horror stories comes at the expense of more positive accounts of women who forcefully rejected or cunningly averted unwelcome advances. “We don’t have role models of women who know how to handle this,” she says. “They’re there, but the culture doesn’t promote it. We promote the victim.” Dodson, it seems, is so sex-positive that thoughts of sex in the negative are so unpleasant she’d just as soon not grapple with them.

When presented with a hypothetical assault scenario—a drunk woman in a revealing outfit walks home late at night and is sexually assaulted by a man—Dodson doesn’t race to pin the blame on the perpetrator. On the contrary: “If you’re going to drink yourself into a stupor, you’re just up for grabs. So you’ve gotta get ahead of that, and not get drunk. Don’t get drunk.” (She goes on to extol the comparative virtues of marijuana.) After a back-and-forth akin to pulling teeth, she finally concedes that blame lies with the male assailant, but includes a caveat: “She shouldn’t be that drunk, and he shouldn’t take advantage of her.”

Dodson describes a life blissfully devoid of sexual violence. But what of unwelcome physical advances? She enacts an assertive brush-off: “Get your hands off of me! Get the f*ck out of here, you son of a b*tch! I was raised with brothers. I can fight. I’ve got muscles.” And while she deplores what she sees as the fainting-couch fragility of women who complain of comparatively minor molestation from men, she concedes that female acquiescence in moments of sexual danger or discomfort stems from societal conditioning rather than essential weakness.

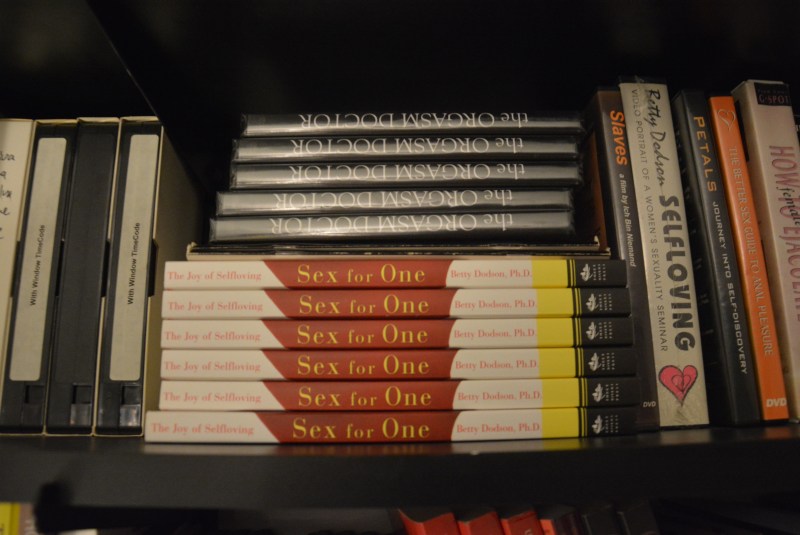

One of Ms. Dodson’s many accolades.

Weakness—of any kind—seems to be antithetical to Dodson’s being. But that doesn’t mean she’s kept up her rigorous physical regimen of years past. These days, the pull-up bar in Dodson’s kitchen doorway gathers dust. “I’m too old,” she says. “The fact that I’m standing is enough.” Her sex parties are long gone, too—apparently, after a while, removing stains of indeterminate provenance from shag loses its allure. Plus, nowadays, “you have to get everyone’s history, have they been tested…. It’s hardly worth it.” Her dejection is palpable. But the gauzy, sexually democratic picture she paints of the parties is idyllic. She concurs: “it’s the kind of freedom we deserve as human beings.”

Unbidden, Dodson offers thoughts on a legacy. “What I represent is the freedom to give yourself an orgasm all on your own, and get the benefit of that moment of energy.” An elegant bowl of vibrators beside her desk underscores the point. “You first have to be self-sexual, and then you can have sex with other people. The love affair—the sex affair—that we have with ourselves is the primary one. It should be ongoing throughout our life, and we should honor it.” To an already self-absorbed generation, this edict from the Oracle of Onanism might come as welcome news; or, at the very least, as self-evident. As for Dodson, she leads by example. “I have orgasms all the time with myself,” she says. “I’m 88, so whatever I’m doing, it’s working.” Maybe the secret to longevity is simpler than we think.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.