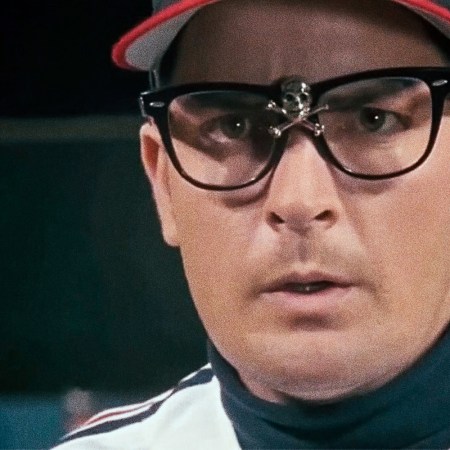

Richard Devine does a pretty good impression of the bleeps, whoops, ding and blips that our world of electronics is now punctuated by. In fact, he often sounds them out before seeking to recreate them on the banks of screens, keyboards and mixing desks that form his working environment. It’s constant play with the pitch and timbre.

The acclaimed Atalanta-based electronic musician has been busy over recent years composing — designing, they call it — just such tiny symphonies for the likes of Target, Barnes & Noble, LG, Coca-Cola and Absolut, as well as for some of the tools of his trade, for Yamaha and Korg. He calls these sounds their “sonic signatures.”

“The fact is that although sound has long been an afterthought to most companies — something they considered only after every other aspect of the product had been decided — now they’re having to think more and more seriously about their sonic signature because so many products have some kind of electronic or electric component now,” explains Devine. “There’s a technological shift with the things we use daily, because [in the age of the Internet of Things] now everything is a device. I mean, I control my dishwasher, even my light-bulbs, using an app.”

Such auditory idents are more considered than may at first be clear. No matter how brief, each little tone, Devine says, has to trigger some kind of emotion in the listener, a reassurance that things are working as they should, “to article the state of the device or system in use.” They should enhance the experience of using the product. The sounds have to be simple, but they have to work within the parameters of the product too, and the limitations of their speakers, which feature a much smaller frequency range than Devine would consider for his music. They have to work across cultural and age boundaries, and differences in hearing. They have to win the product user’s attention without being irritating or distracting.

“You have to remember that some people will hear these sounds maybe hundreds of times a day, so you have to ensure various sounds work together tonally as a family, without making people want to kill themselves,” laughs Devine, who has a side gig as Apple’s senior content producer. “You can spend months trying to come up with the right sound.”

All this and, increasingly, these chimes and bongs have to express certain company characteristics, or, at least, brands aspire to do this. Devine cites his work for Google, which wanted clean, rounded, simple sounds, nothing edgy or overly complex because, it believed, these qualities echoed its brand values. Audi has even developed a library of sounds that it deems appropriate for its various models.

If that sounds like it’s pushing the role of a few notes to a breaking point, Devine gives by way of example the “bubbly” sounds that have come to be intimately — if unconsciously — associated with Skype or Nintendo. Get it right and the association with a certain brand can be strong: McDonald’s do-do-do-do-doo and Intel’s be-ba-ba-bong are good examples. A sonic signature, whether used by a product or in a brand’s advertising, becomes a “sonic logo.”

It’s the awareness of this that is seeing car companies in particular turn to Devine. The likes of Audi, Porsche, the electric supercar company Lucid and Jaguar. Why? Because while the makers of upscale cars have always sought to push for an engine sound that’s characteristic of their marque — think of the high squeal of a Ferrari, or the guttural rumble of an Aston Martin — said sound has been constrained in part by the physics of combustion engine engineering. But with the advent of electric motors, suddenly a car can sound like anything at all. Some car companies are embracing the fakery and simply seeking to mimic their combustion engine note. But others are turning to Devine to wizard up a whole new artificially generated soundscape for under the hood. And with good reason.

“The fact is that Jaguar, for example, has a fair history of making great sounding cars and tuning the engine sound to match the product,” explains Iain Suffield, noise technical specialist for Jaguar. “The trick is create sounds that feel natural and authentic to the EV model in question, while not going so far that you break the illusion, or create a sound that ages badly or becomes passé. And that’s really not easy.”

As Devine points out, designing the sound of our future cars is “fast becoming a specialist discipline, not just because there’s an opportunity to make the sound part of the brand of an electric vehicle, but because there’s so many conditions the sound has to work in. It’s not just enough to have a great sound. That has to work against a background of other ambient sound, or against wind and rain noise, and also in various urban environments or in open country.”

Devine’s solution for its I-Pace EV? A harmonic blend of Jaguar’s conventional engine “purr” mixed with something, he says, akin to the pod racers from Star Wars or the light bikes from Tron. After all, if an EV is meant to herald the future of personal transport, why not make it sound somewhat futuristic? In the EU, at least, legislation now means that EVs must make some kind of sound. They can run silently, after all, but this is problematic to pedestrians long attuned to using their ears as well as their eyes to judge an approaching vehicle, not to mention their import to driver feedback. Artificial or not, a sense of the car moving up or down through gears — as non-existent as they may be — still adds to the driving experience.

“Likewise, you can see that in time that the sound scheme that a product has — whether that’s a car or a dishwasher — will be part of the reason why we buy it over a competitor’s, because we all know how sound can affect us,” he says. “Sound will be considered as much part of the product’s appeal as its look and function is.”

That, he stresses, is in no small part down to the fact that the means to record sound are getting ever more sophisticated: Devine went out into the wilds with 200 ambisonic microphones in order to devise a world of sound environments for Google Earth. But our products’ ability to use, convey and project sound is changing, too. Devices that were once professional standard equipment, the likes of VR headsets, are entering the consumer space at breakneck pace. Spatialized audio — which, following 360degree video, creates a more 360degree, immersive sound experience, for example — is already available in the latest generation Apple AirPods.

“So changes in tech,” says Devine, “are both going to stretch how we experience sounds and, in time, move us towards a more intelligent understanding of how the products we use use sound. When it comes to the sound our stuff makes, we’re only just getting started.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.