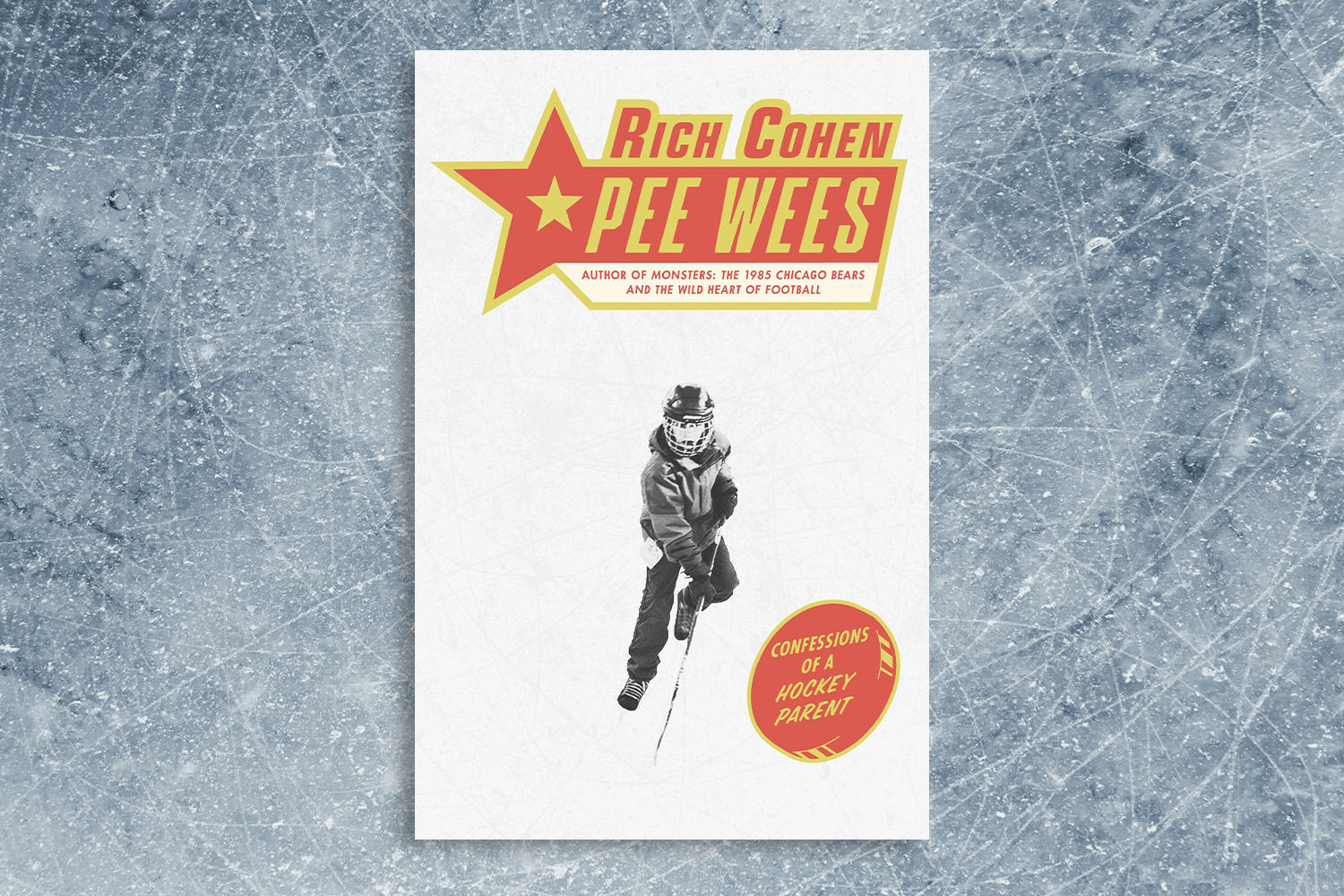

“I think it’s maybe the most important book I’ve ever done,” says James Patterson. Coming from a man who has authored 241 New York Times best-sellers, this is quite a statement.

He’s talking about Walk in My Combat Boots (Little, Brown and Co.), which hits shelves today, February 8. Speaking over the phone, Patterson swells with pride. “It’s just a stunning friggin’ book,” he says.

Like his other recent projects, including a true crime account of John Lennon’s final days, Combat Boots is nonfiction. And like the vast majority of Patterson’s books, this one is co-written. Although Patterson has worked with some high-profile collaborators (see: Bill Clinton), he credits this particular partnership with producing such a powerful text.

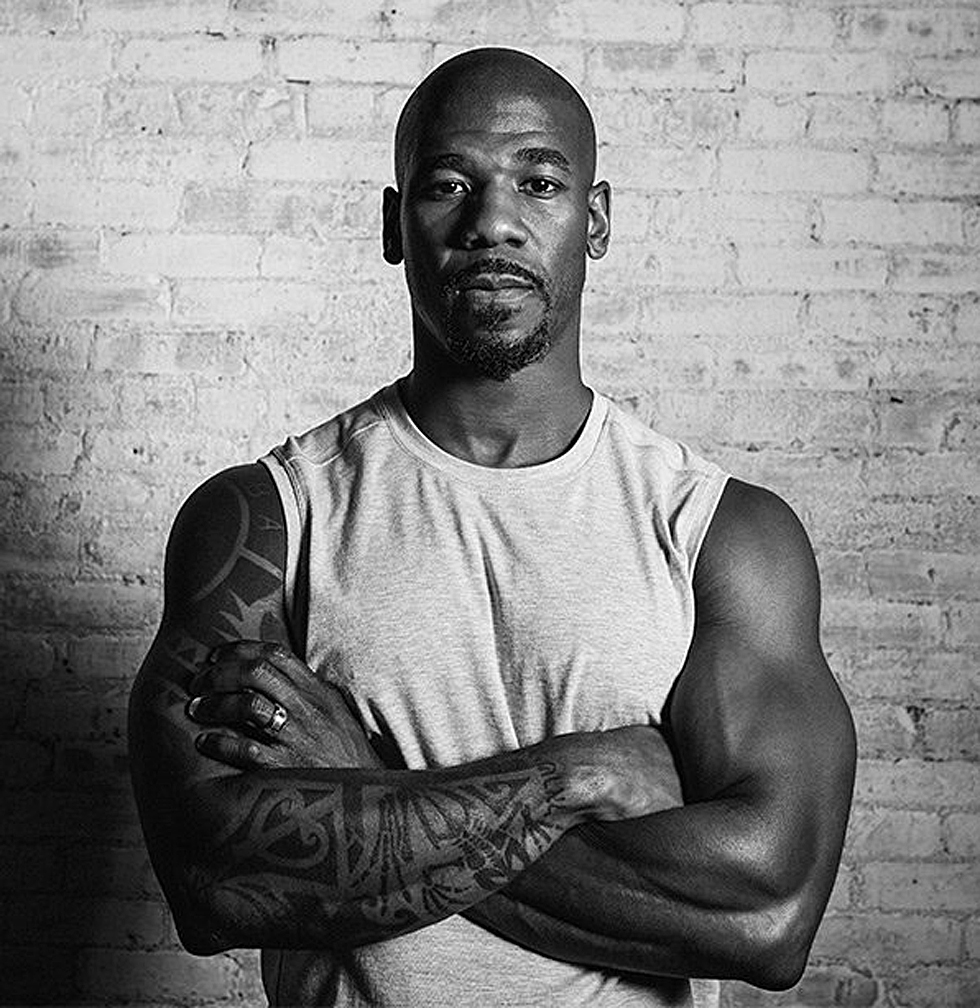

Matt Eversmann, Patterson’s co-author, is no stranger to war. Or war stories. As part of the vaunted 75th Ranger Regiment, Eversmann was one of the special forces soldiers who fought in the Battle of Mogadishu. Their daring survival story was immortalized in the 2001 blockbuster film Black Hawk Down, where Eversmann was portrayed by Josh Hartnett.

“That’s the most absurd sensation in the world,” Eversmann says of seeing an actor play him on the big screen. “It might even be more surreal than the beginning stages of combat, when you’re like, ‘Wow, somebody’s actually shooting at me.’”

After 20 years in the Army, he retired in 2008 but continues to lead a life of service. Eversmann Advisory, the organization he founded with his wife Tori, is dedicated to helping soldiers avoid “the veterans’ predicament” as they transition to life back home. He’s also maintained a connection to active-duty troops by visiting combat zones to interview soldiers.

Patterson saw some of these interviews and was impressed. “When people come back from combat, they won’t talk to civilians. Even their families,” he says. “Like when my father came home from World War II, he never spoke about it.” But he noticed that soldiers were opening up to Eversmann.

For his part, Eversmann is humble but self-aware when accounting for this.

“When you’re talking to these men and women, first of all you’ve got a little bit of bona fides as a veteran yourself. And second of all, to have been deployed and experience combat a couple of times as I did in Somalia and then in Iraq, it would give anyone the credibility to have very direct –– thoughtful –– but very direct conversations.”

Inspired by the candid and emotional stories Eversmann elicited, Patterson approached him about doing a book together. Every collaboration, Patterson explains, is different. For this project, Eversmann conducted dozens of interviews with soldiers and veterans. After each conversation, he reviewed the transcript –– 30 to 50 pages apiece –– and highlighted the most compelling elements. Every week, he drove a batch of annotated transcripts to Patterson’s Palm Beach home. They discussed the interviews, and then Patterson had the task of boiling each one down to a short story that maintained the truth of the individual’s experience.

Walk in My Combat Boots is a compilation of these stories. What sets it apart from other war narratives is that it trains a spotlight on the men and women who seldom occupy center stage. While it features many white-knuckle accounts detailing the graphic realities of combat, it also strives to celebrate the men and women whose critical service is often overlooked.

“In the past 20 years, post 9/11, there’ve been some very sensational stories about combat. I mean sensational in a good way,” Eversmann says. “But I wanted to make sure that I, as the interviewer, wasn’t just going through all my Ranger buddies, Delta and SEAL friends. It’s not just another chapter of Black Hawk Down or Lone Survivor.”

It really isn’t. Combat Boots captures the breadth of military service through sweeping yet intimate vignettes. I can only speak for myself as a civilian reader, but I was totally ignorant of many of the military jobs represented in this book, let alone the physical and emotional duress attached to all of them.

There’s a flight nurse who’s tasked with treating wounded soldiers while flying in and out of combat zones, often under fire. She describes one mission where her commander tells her they are flying three fatally wounded soldiers to Walter Reed. Her job is to keep them alive long enough so they can die on home soil.

There’s a truck driver whose job is to transport fuel to remote operating bases. His convoy takes the same route every day, which makes it easy for the enemy to attack them with IEDs (improvised explosive devices) every day. When his truck gets hit, he is furious but not surprised.

There’s a supply and services officer who becomes the Army’s chief of mortuary affairs ahead of Desert Storm. In other words, he oversees the logistics of death. Before a single American enters Iraq, he’s given the impossible task of designing a plan to transport the remains of 7,000 soldiers who could potentially die in chemical attacks. Thankfully the grim projection never materializes.

There’s a Black Hawk pilot who deploys as a single mother. She’s responsible for bringing ground forces to and from objectives in Afghanistan.

And there are many more.

One aspect of this book that might surprise readers is how many women serve in the military. “I think we were able to address that without any kind of agenda,” Eversmann says. “They’re soldiers that just happen to be female. We’ve got a bunch of them. And they’ve got great stories.”

The youth of the soldiers is another recurring theme. Many of them are 18 when they enlist, or even younger with parental consent. Some of them are floundering in school or menial jobs, and the military offers structure and opportunity. Others defer their education and professional dreams in order to serve. All of them share a sense of duty and purpose. Their responsibilities and conviction stand in stark contrast to the arrested development that’s plaguing an entire generation.

“We’re wondering whether kids who are going to be freshmen in college are going to be able to do their laundry and shit like that,” Eversmann says. “And then there are 18-year-olds that are walking through the Hindu Kush mountains in the shadows of Tora Bora, carrying guns, who will literally go kill somebody today.”

Despite the heavy subject matter, Combat Boots features humanizing moments of levity. One lieutenant who has just arrived in Iraq describes how his digestive system is struggling to adjust. He’s still getting to know the group of men he’s leading. They’re on a patrol, hiding in a house in Baghdad, when nature calls. “The bathrooms are outside, and I can’t go out there because that will give away our position,” he says. He notices an armoire big enough to step inside. A few minutes later, one of his soldiers rushes into the room because he heard the lieutenant making strange noises. The young man asks the lieutenant if he’s okay. “I’m shitting inside someone’s closet right now,” he says. “How do you think I’m doing?”

Of course, the book’s overall tone is solemn. The most difficult issue that these stories illuminate is the perpetual struggle veterans face when they attempt to assimilate back home. One soldier shares a startling statistic: “The number of service members we’ve lost to suicide is by far greater than the number of service members killed by the enemy.” Eversmann acknowledges that this weighed heavily on him when conducting interviews.

“Talking to people about battle is talking to people about battle,” he says. “I don’t mean to sound so cavalier. But the emotional side of it is a challenge. How do you have a conversation with somebody that’s like, ‘Yeah man, I was in my truck, I had my Glock and I was just sitting there thinking it’s time to check out’?”

Like Eversmann, many veterans have dedicated their post-service lives to helping other veterans. Combat Boots raises awareness for their important work with chapters from the founders of organizations like Stop Soldiers Suicide and Eagles & Angels. But the most immediate way this book helps soldiers is by giving them a platform.

“Typically, with books about the military,” Patterson says, “a general or some historian will tell a story. Or maybe a poetic man or woman who’s been in the war will come back and write a novel that’s poetic and interesting. But the grunts don’t get to tell their stories.”

Civilian readers can only imagine how important it is for veterans to hear these stories. To know they’re not alone and to feel visible. But reading these stories can have another powerful effect for civilians.

“There are so many people in our country that have been living in the post-9/11 world that have never met a soldier,” Eversmann says. “Not once. That is, on one hand, a head-scratching phenomenon. But it just shows you what so few are doing for so many.”

If I’m being shamefully honest, I’ve always regarded “thank you for your service” as somewhat of a platitude. A well-intentioned but abstract greeting we automatically offer veterans. These stories are concrete reminders of what we’re thanking them for.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.