“Robots that feel alive aren’t going away,” writes Kate Darling.

Darling is an expert in robot ethics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and it’s a fascinating time for her field. More and more we are beginning to outsource tasks to the awesome power of artificial intelligence. Robots, like those that dance in the videos released by Boston Dynamics, are increasingly good at mimicking human behavior; in Japan, Toyota is developing a humanoid robot that may someday aid doctors in performing remote surgeries; some of us are even treating robot companions like replacements for real people.

The robots, as Darling says on the back of her new book, are here.

But Darling also wants to issue a word of caution about this changing landscape. In The New Breed: How To Think About Robots, she proposes that we would do well to liken robots not to humans at all, but to animals. “Comparing robots to people is limiting,” she writes. “I want us to be able to think about robots in a way that doesn’t succumb to moral panic or deterministic narratives.”

Darling talks to me from her home in Cambridge, Boston. She is pregnant, her second child due in a few days. When she says, “I’m ready for this to come out,” she could be talking about the baby or her new book, which is set to publish a week after the birth.

Darling grew up middle class in 1980s Rhode Island, with a computer programmer for a father and a mother who worked in education. Because of her dad’s work, her family was always the first to get the latest technological development: email, a CD burner. She became interested in robots mainly because she read the sci-fi her dad left lying around the house. What appealed to her most were the authors who wrote not primarily about technology, but about broader societal changes. “Good science fiction really opens your mind to what could be possible and makes you critically question the current state of things in a way that other literature is maybe not quite as on the nose about,” she says.

As a kid, she says, she was an “outside-of-the-box thinker.” When she was nine and the family moved to Switzerland because of her dad’s job, she got in trouble because the country places less value on creativity and freedom. After going to law school, she did a PhD in Zurich. She has always been “Extremely Online” and read Gizmodo and Wired. “All I would talk to people about was robots — all day — especially in bars when I was drunk. You couldn’t get me to shut up about robots.” Various people from MIT followed her on Twitter and, after her PhD, she got a job in the Media Lab.

Around this time she bought a baby dinosaur robot called a Pleo, to which she would respond emotionally because it was so good at simulating real behavior. It was around then that she started remarking that we’re always comparing robots to humans, not animals. “Most people haven’t made the connection because none of our narratives really incorporate the animal comparison.” It makes sense that we give robots agency, she says, but we shouldn’t give them too much: it starts to create a humans-vs.-machines narrative. If we think of them as animals, we see them more like a supplement, and less as an adversary.

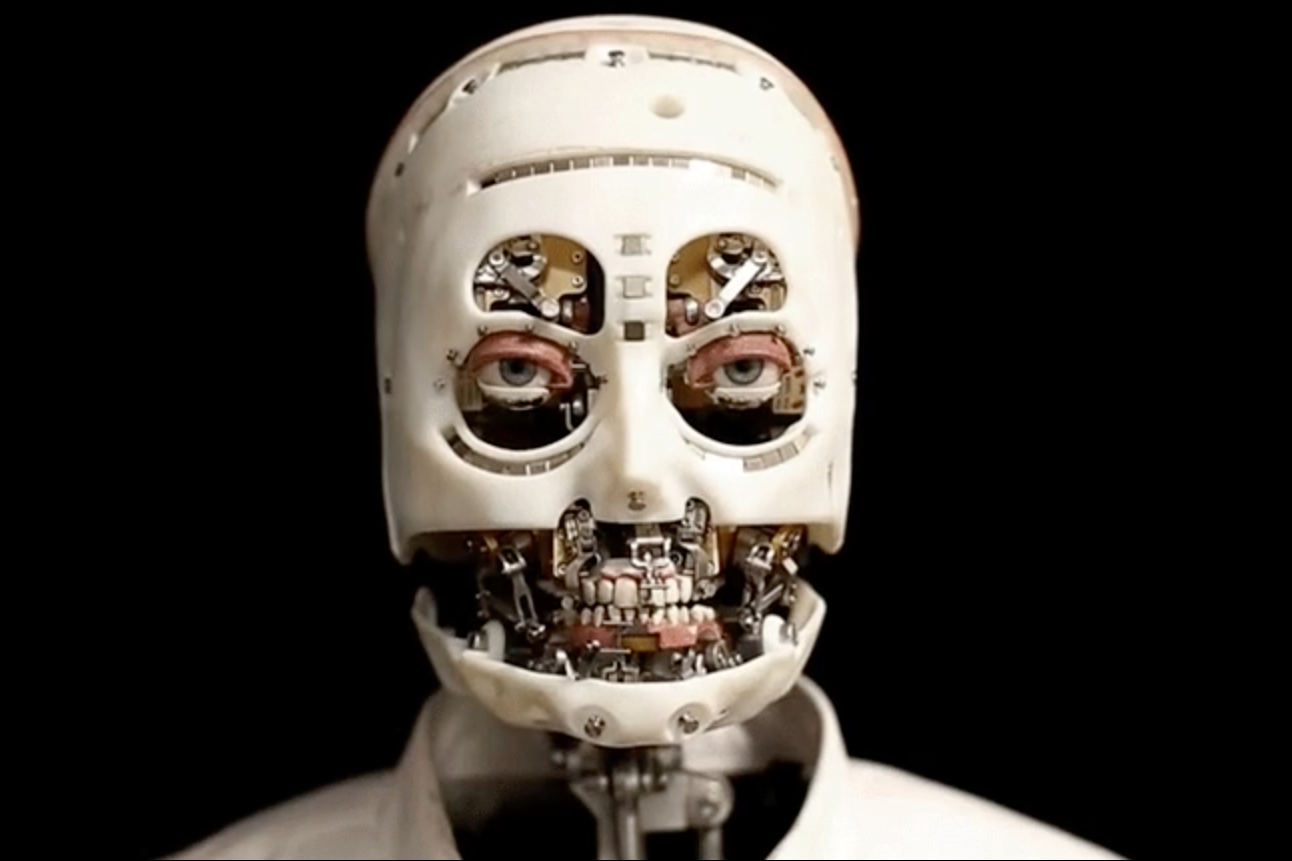

Darling’s is an optimistic book. The media like to declare, in articles illustrated with a photo of the Terminator, that robots are going to take our jobs. Darling knows that this is sensationalist. “We completely overestimate the abilities of robots to do most human jobs,” she says. Many tasks can be automated, true, but when Elon Musk tried to automate his Tesla factory, he couldn’t, because our skills are so different. If a screw falls to the ground in a manufacturing hall, a human can pick it up. A robot cannot.

The “taking all our jobs” narrative pits robots against humans unnecessarily. Darling points out that we’ve apparently been 25 years away from robots replacing humans for many years. The adversary isn’t robots, Darling says, but the decision-making behind them. “It’s humans versus humans,” she says.

In Japan, for example, an over-aging population and low birth rate have been blamed on artificial companions and girlfriend pillows. “It’s not clear to me at all that that’s the issue,” she says. There’s been considerable investment in robots because the disproportionately elderly population have so few careers — their utility is a necessity, not a redundancy. But robots can’t solve everything. “Sometimes there are solutions to a problem that aren’t just sticking a robot into a nursing home,” she says. Robots should play the same role as therapy animals: supplementing human care, rather than replacing it.

Darling knows that we will never stop anthropomorphizing robots, and animal research has acknowledged that we miss things when we don’t anthropomorphize animals. But we need to be “aware of the limitations” of this biologically embedded tendency. One fascinating section of her book details how, in the 15th century, humans put animals on trial — even appointing attorneys for them — because we believed that they could be held morally accountable for their crimes.

She worries that there are signs of that mentality returning, with some people now writing papers about holding robots accountable for crimes. In 2016, the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs suggested (with no luck) a legal status for robots which would make them, not their creators, liable for harm. Here, Darling points to the reason we stopped taking animals to court: they cannot be assigned human responsibility. And neither can robots.

“I’m not suggesting that we treat robots exactly like animals under the law,” she writes. “I’m suggesting that there are more ways to think about the problem than making the machines into moral agents.” We have many different ways of responding to harm done by animals that date back millennia. We can and should apply the same nuance to harm done by robots, she suggests.

A good example of the way in which robots are products of the people who design them is the inherent sexism that gives, for example, IBM’s supercomputer a deep, male-coded voice and the AI that turns on the lights a female-coded voice. “That seems like low-hanging fruit to me,” Darling says, “when people just aren’t thinking about how they’re programming their own biases into the technology.”

It reinforces the idea that robots, even those that can think for themselves, are what we make them. “If we care about using robot technology to advance human well-being and flourishing,” Darling writes, “then we need to look beyond the robots and instead to the systems and choices that put that at risk.”

The New Breed: How to Think About Robots is out now.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.