“Everything in the world is about sex,” Oscar Wilde famously said, “except sex.” Sigmund Freud would agree with the first half of that. To Freud, everything is about sex. Full stop.

This worldview has shaped his reputation as a dirty old man, which is not wholly undeserved, but the headline shock value of his ideas often clouds most people’s understanding of the man and his work. If you ask the average person what they know about Freud, you might hear something like, “Isn’t he the psychologist who did a lot of coke and thought all boys want to sleep with their moms?” That’s not wrong, but it’s not all.

As a practicing psychologist, Freud’s primary focus was treating his patients and helping them overcome various neuroses. It just so happens that every neurosis, he believed, is related to sex. Even though many of Freud’s controversial theories have been debunked by modern science, particularly those relating to female sexuality and gender identity, he’s still relevant in today’s world.

Freud’s work remains the basis of modern psychoanalysis, “the talking cure,” and many of his concepts offer compelling explanations for puzzling human behavior. His notion of the repetition compulsion, for example, is the idea that a person repeats or re-enacts a traumatic event over and over again. Freud would use it to explain why your friend always falls for the same kind of girl even though it never ends well, or why Andy Reid always mismanages the clock, or why Anthony Weiner can’t stay away from social media.

In the spirit of Father’s Day, we decided to conduct a little thought exercise: How would Freud interpret different aspects of life and fatherhood in 2021? To ensure we remained faithful to his work, we enlisted some professional help.

Amy Rodgers is an associate professor of film and media studies at Mount Holyoke College. She specializes in early modern literature and culture and is well-versed in Freud, among other major theorists. In the interest of full disclosure, I’ve taken several graduate courses with her and have long admired her mental agility when it comes to popping in and out of the minds of various thinkers. We connected over Zoom earlier this week and spent some time looking at the world through Freud’s owl-eyed spectacles.

Our conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

InsideHook: Let’s start at the beginning. How was Freud’s relationship with his parents?

Amy Rodgers: He was born in the 19th century with very, very German-Jewish parents. He was very smart and he was pushed, but he would understand his relationship with his own parents as problematic. He’d say he was deprived of love by his father and some of that was given to him by his mother, but the love of the mother does not replace the approval of the father. Freud understands the relationship between fathers and sons as inherently antagonistic.

How so?

The way he understands male children, and this is all very patriarchal, is that they move into the world of heterosexuality through different stages. First the son identifies with the mother because she provides all his sustenance. And then one day he realizes that she doesn’t have a penis and is horrified. And then he comes to believe that his father must have cut it off. So then he becomes afraid of the father. Eventually he comes to see the mother as inferior because the father was strong enough to overcome the mother. And in that way he will also learn to desire women by identifying with the father rather than identifying with the mother.

Quite a hero’s journey. Okay, so obviously there’s a lot about Freud that’s problematic. How’s he regarded today?

Freud has fallen seriously out of fashion for all kinds of reasons. One because he is representative of a kind of patriarchal point of view that understands women as inherently lesser than men. This is largely through his concept of penis envy. But the notion that women are lacking [a penis] and men have the actual intact entity is not novel to Freud. Galenic medicine, which was practiced for a very long time in the west, believed that women were just physically men who did not get enough heat in the womb.

Wait. Like thermal heat?

Yeah. Like they were deprived of heat in the womb and so all of their junk, if you will, just stayed up there rather than falling down. And so there was a lot of panic in the early modern period that women, if they got overheated or did too much exercise, their stuff would fall out. So that’s why if you look at dance manuals from the period, women were not supposed to do very vigorous dancing.

Lest their sex organs fall out the bottom?

[Shrugs sarcastically.] They could. And then society would fall apart. Obviously.

Even though Galenic medicine sounds ridiculous, they didn’t know a lot about women’s anatomy because for a very long time things like autopsies were forbidden. Freud enters the realm of the psyche and says, “it’s not that women are anatomically inferior in any way, but they’re psychically damaged because they learn that they don’t have a penis.” And then they develop this thing of always wanting one.

How do you feel about Freud?

I like Freud. I mean, I don’t know if I would’ve liked him. I think he probably would’ve been super weird. But the thing I always tell my students — and I teach at a historically women’s college, and when I teach Freud to my students they’re going to be kind of naturally disinclined towards him — he was the first person who imagined that people with mental illnesses could get better. In my mind, that is a huge moment in the treatment of psychic illnesses instead of just locking people away.

What made him think mental illnesses were treatable?

Freud’s big belief is that all mental illness is related to sex. Like human beings are just naturally fucked up about sex. That’s just the way we are. He also believed, very unpalatably, that if you were a homosexual, that was a pathology. He thought often if a man or a woman was attracted to the same sex, it was because of something that happened with their upbringing and their relationship with their father or mother. And— [coughs]

Are you okay?

I just swallowed a bug.

Yikes. What would Freud say about that?

That’s a good question. He would say there are no accidents. It was my ferocity that has been suppressed by the social world and the necessary ways in which feminine sexuality has to be contained, so swallowing the bug was a kind of attempt to regain control.

The devouring mother.

Right.

But back to his views on sexuality.

I don’t agree with his things about how cathexis in childhood leads to one’s object choice in sexuality. But the idea that sexuality is, for most cultures, one of the foundational acts that has to be managed and controlled, I do think is true. There are very few, if any, societies that don’t police sexuality in one way or another.

Right. He’s not wrong about that. Let’s shift gears to the present. What would Freud say about Father’s Day?

I think Freud would say that it’s a kind of false moment of familial harmony where we celebrate the figure of the father. It also reifies the father’s position as head of the household. He would say it’s a kind of cultural ritual in which the father can believe safely that he’s the head of the household and is sort of worshiped, which then conceals the constant risk he’s always at by overthrow from his offspring, particularly his male offspring.

What about “bring your child to work day”? Would Freud say it helps resolve the Oedipal complex by allowing kids to identify with their parents?

I think he would’ve really liked “bring your son to work day” in the 19th and early 20th century, and I think he would not like it now. In my own household, my spouse is in school and my kids have grown up knowing me as the person who goes to work. Freud would say that’s really bad because the roles of who supports the family are very old roles. The man is the hunter who kills the mammoth, the woman cooks and does domestic stuff.

This is a kind of radical potential moment of disruption. He might say — and this would be a very unpopular opinion — that some of the current “gender trouble,” to use Judith Butler’s felicitous phrase, is happening because of some of the confusion of familial roles that are supposed to be assigned to certain genders.

So this is kind of a weird question, but I’m curious about belly buttons. You know how dads often cut their newborn’s umbilical cord in the delivery room? Would Freud have anything to say about that?

Oh yeah. I think he’d say that it’s a strong first gesture towards the son ultimately having to separate from the mother and attach to the father and emulate the father. So that symbolic cutting, which of course the child can’t do right away because the mother is a source of sustenance, is kind of a predictive moment of the natural line of cathexis the child should follow. It’s a similar ritual to — we don’t practice this anymore, but in the early modern period — aristocratic women didn’t nurse their own children. They worried that the child would get too much of the mother’s self through the milk. There are a lot of lines in Shakespeare. “He has too much of the mother in him.”

How would Freud interpret our cultural fascination with dad bods?

I recently got an advertisement on my newsfeed for a T-shirt that said, “It’s not a dad bod, it’s a father figure.” Freud’s idea of the father is somewhat mythic. A father’s not just a man whose seed has contributed to the birth of the child. He has to have a mythic presence in the mind of the child. And the mythic presence should be almost god-like. Like the early speech in Hamlet where he compares his father to the god of the sun.

The idea of the dad bod, Freud would say, is a kind of tearing down of the necessary portrayal of the father as a kind of mythic figure that the child needs. I think he would see our own culture as very degraded around sexuality because it doesn’t have a clear end point. For Freud, the end point for a healthy society is heterosexuality with a companion in marriage with a nuclear family. The dad bod is a signal of how the omnipotent male is starting to be dismantled by society.

In a similar vein, I’m curious what Freud would think about the proliferation of companies like Hims and Roman. You know, all the companies that address taboo male health stuff like erectile dysfunction or balding or whatever.

This is where I would say Freud is still really embedded. It isn’t just Freud. It’s western culture. The amount of money and R&D that goes into fixing ED is astronomical. I always say that if men had to have children, there would be a painless, risk-free way to deliver babies. But the obsession with ED comes out of the idea that in order for a man to be a man, he has to be able to perform sexually. There’s no real reason to think that. What is the reason to think that an 80-year-old man needs to be able to perform sexually? Let me tell you, as a very middle-aged woman, at some point you’re like, I don’t care! I don’t think I’m there yet, but you don’t want your 80-year-old husband groping you. Goodbye.

But when gods like Hugh Hefner appear on TV saying they wouldn’t have lives without Viagra …

Yes! And that is a cultural fantasy that is very much related to masculinity, and the potency of masculinity is something Freud identified about culture. He believed it too. But he understood there were many problems with it. That’s why he got in the practice — to get everybody up to that level. I think Freud would be pro-Viagra. I’m sure he’d be taking it.

What would Freud say about dating apps?

They’re difficult because they’re so varied. I think they’re kind of similar to social media. There are id dating apps, and then there are superegos. Like the “I want to find the right person to get married” app, and then there’s “I just want to hook up.”

How about the apps where the woman has complete control over if the man can even message her?

I think Freud would find that fascinating. He would certainly see that as a move away from bourgeois patriarchal culture, but I bet he’d connect it to earlier matriarchal societies. But also, some social liberties are often availed in order to keep the status quo in place. So one could ask, does this really change anything about the dynamics of many male-female heterosexual relations? Maybe. Or is it just an illusion of agency in order to preserve a greater structure of dominance?

I wanted to end by asking about COVID. I’ve been thinking a lot about Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, and I’m wondering what Freud’s plague journal would look like. What would his takeaways be from the past 18 months?

Foucault is really the person we want for this question. But I think Freud would be interested in the way the nuclear family became re-prioritized in our lives. Because he’s very interested in how our relationships with sexuality allow for the preservation of the family, which he sees as a necessary entity in society.

I also think he’d be interested to see a study conducted over the next 18 months, like if we’d see any changes in human behavior around sexuality. He’d probably want to track if we see a move back to a more binary form of sexuality. Like we’ve seen a move away from that — not entirely, I don’t want to overstate that — and he would want to understand if that bore out his theory about the nuclear family’s significance in preserving the bourgeois capitalist state.

What about the fact that men had such a hard time wearing masks compared to women?

Freud’s idea is that heterosexual masculinity demands a certain belief in one’s infallibility — even if he would say it’s not true. The development of the heterosexual male has to be aspirational. The son has to aspire to emulating the father. To bettering the father. To having more than the father. To continue climbing the ladder of success. That yokes it to this idea of capitalism. In so far as Freud is interested in capitalism, which he isn’t particularly, he’s interested in the way it works in tandem with sexuality to produce a kind of infallible masculinity. But! He’d also say there’s a kind of hinge point. The moment when the man thinks he is greater than God. Is the mortal overstepping his own potency? Freud sees this as dangerous.

Like Trump flouting masks and social distancing and then getting COVID?

Yeah, Trump is so interesting. We’ll be talking about him a little in this masculinity class I’m teaching. Part of his appeal is that he was able to convince people of his machismo. The three wives, the model, the kids, the wealth. That narrative is very old. It goes back to — and this is a word that’s frowned upon now — but the primitive idea of rulership. But it’s one that’s entirely mythic.

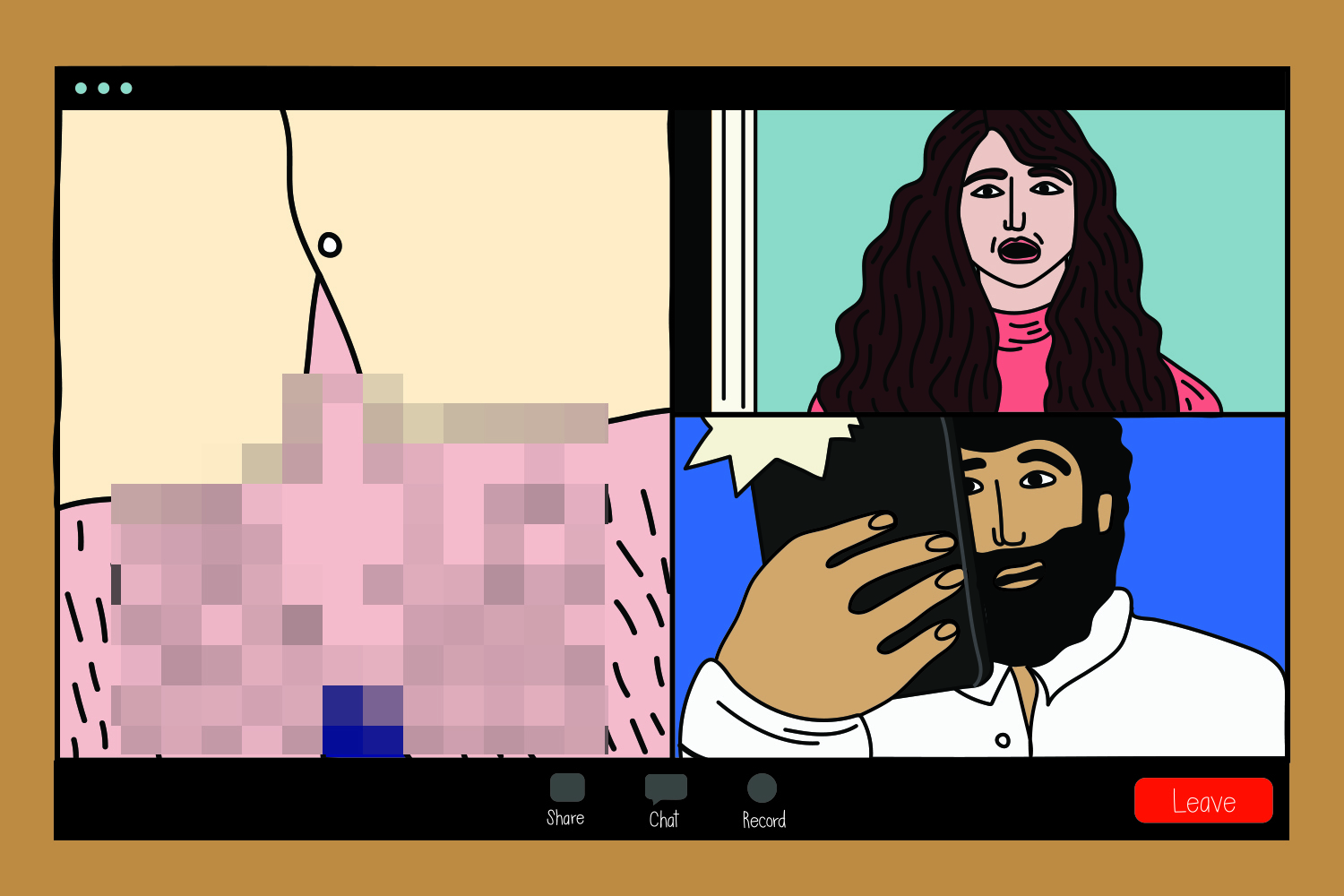

That raises the question of how myths are minted in our culture. What would Freud say about social media?

I think he’d say it’s the id, that part of you which has been taught to be repressed by the superego. Social media has become this outlet for the id because you can be faceless. At the same time, social media has also become a super effective superego. Just look at what’s happened with Chrissy Teigen.

I think Freud would be interested in the way social media facilitates myths. It’s very easy to be someone you’re not, where appearances become almost interchangeable with a kind of tangible reality.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.