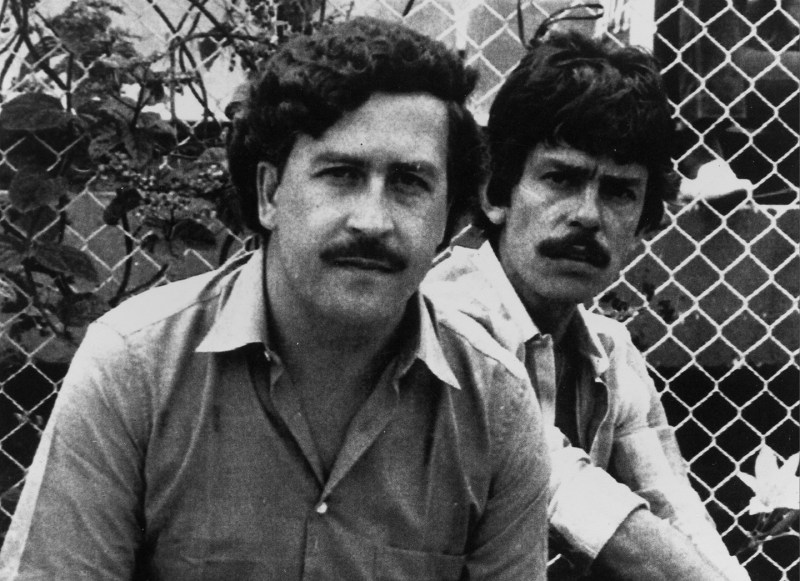

In 2009, Roberto Escobar released The Accountant’s Story. The book tells what it was like to be both the brother and, yes, accountant to Colombia’s late King of Cocaine, Pablo Escobar. The Los Angeles Times described it as “less a memoir than it is an apologia” and “frankly, repellent.” This work is, however, unique as a portrait of people attempting to handle a fortune in illegally acquired gains. Roberto recounts initially using bank accounts and more conventional money laundering, but quickly having to resort to just hiding money: putting it in warehouses, stashing it in random walls, burying it.

Meanwhile the money came in such massive quantities Roberto estimated that they spent $2,500 each month on rubber bands for the stacks. Indeed, they were so overwhelmed that they wrote off 10 percent of the cash each year as destroyed by mold or rodents.

With so much money handled in often haphazard ways, it’s reasonable to think a lot of it remains undiscovered. (For instance, in 2016 a safe was found during the demolition of a mansion in Miami Beach that Pablo Escobar once owned—it is supposed to be opened after the completion of a documentary about the residence.) Discovery in particular is convinced the loot is out there, as they’re premiering Finding Escobar’s Millions on November 3. The series tracks former CIA operations officers Doug Laux and Ben Smith as they “work with the original DEA agents that handled the case to infiltrate Escobar’s inner circle in search of the cash.” Discovery also boasts they will have “unprecedented access to technology” and “numerous inside sources to scour Colombia for the money.”

Yet the fact remains: Pablo died way back in 1993. (It feels more recent thanks to his constant portrayals on both the big and small screen.) Considering over two decades have passed, how does one even approach the task of uncovering what remains?

Liseli Pennings served as a Special Agent with both the U.S. Treasury Inspector General’s Office for Tax Administration and the U.S. Department of State Diplomatic Security Service before becoming the Training Director for the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. She acknowledged the amount of time since Escobar’s death makes the task “that much more challenging.” Additional obstacles include the fact much of the information involving Pablo is “probably not online”—the internet has been a boon to law enforcement investigators—and a good percentage of surviving assets are likely overseas where “access to things is not always as clear-cut as it is here.” (Indeed, records may not be accurately kept at all.)

Beyond this, there are the usual frustrations investigators face. When “you deal with humans, there’s bound to be an error somewhere along the way”—an apparent breakthrough can turn out to be a dead-end because records were filled out incorrectly at some point. Finally, if Roberto’s account of ten percent of the cash being destroyed annually is correct, it’s possible millions and millions in hidden assets have been simply lost.

Nevertheless, Pennings laid out some of the tip-offs that can help track anyone’s hidden assets, even Pablo’s.

Get the records. Court records, property records, credit card records, telephone records, business filings, wire transfers, litigation history… the more information you acquire, the better your odds of understanding what they possess and where they may have it. (And yes, there is an excellent chance they’ll have set up shell companies or tried to conduct business in “locations that are considered tax havens.”)

Money in motion. In general, people with ill-begotten gains are seeking ways to make those assets look legit. A simple way to do this is to “keep moving funds back and forth so that it muddies the process.” (These assets haven’t been fully laundered, but at least their origins are difficult to track.) The result is that money may be shuffled from one bank to another “back and forth, back and forth.” The discovery that assets either have been or still are being constantly shifted around is an excellent sign you’re approaching something they don’t want you to find.

The giveaways. Who pays more in taxes than they owe? Or happily racks up losses at casinos before cashing out? Or cashes out of life insurance policies even though they have plenty of money in the bank? All of these behaviors are typical of people looking to launder assets, since the money they get back is “clean.” (The IRS overpayment is particularly ingenious: “They usually do that because the IRS will then submit a check to you with the amount that you overpaid. It looks like that money is now coming in from a legitimate source.”)

The call of cash business. These include “night clubs, restaurants, casinos.” Perfect establishments to own if you’ve been making money that you shouldn’t have and are looking for a plausible reason to explain why you possess it.

Keep it in the family. A common tactic is to “falsify sale of property to or from family members or known acquaintances” where they “transfer a title but not the possession.” A particularly “big red flag” is the discovery of “businesses in the name of the children.”

This is why Pennings said that, if she were put on the Escobar case, she would begin her search by examining his intimates: “Typically money is hidden under names of children and spouses and close associates.” In a twist Pablo could not have envisioned having died before the internet became ubiquitous, she observed that “social media platforms” are an excellent means of approach.

It should be noted that the Escobar clan may be poised for a big windfall : Pablo’s brother Roberto made headlines recently when he announced he was demanding $1 billion from Netflix for using “all the trademarks to all of our names and also for the Narcos brand” without paying the Escobar family royalties. Meaning Pablo’s drug notoriety might be about to bring his loved ones a final unexpected score.

Here’s a sneak peek of Discovery’s upcoming series.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.