By Michael Nolledo

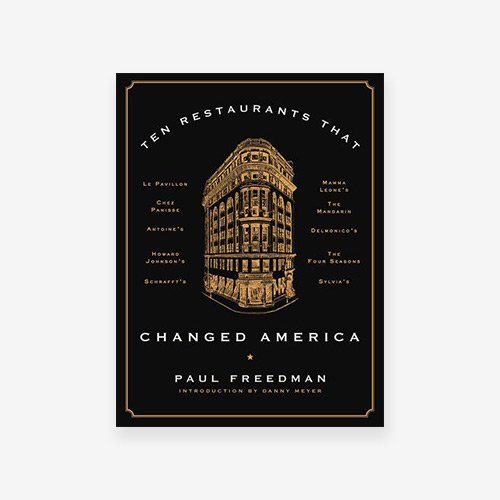

This week, Delmonico’s — a New York steakhouse that bills itself as America’s first restaurant — celebrates its 180th anniversary. We recently paid them a visit to figure out how the putative “first restaurant in America” remains intact to this day.

So much has been written about Delmonico’s that it’s difficult to know where to start.

But I’ll begin with the night the restaurant closed (so to speak): May 21, 1923.