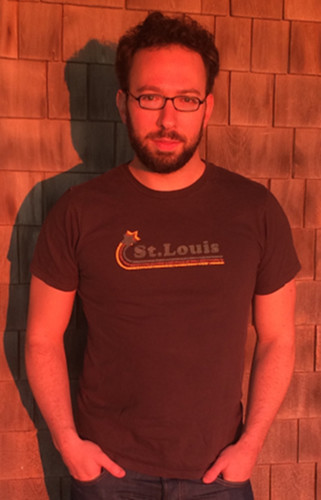

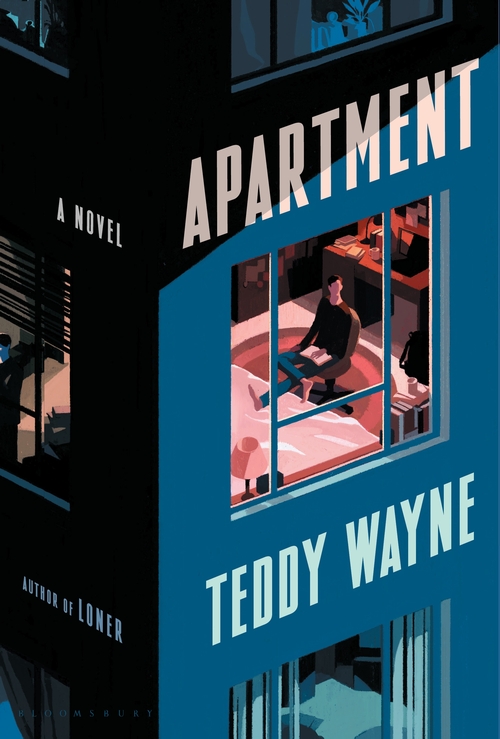

How do you best explore questions of politics, sexuality and masculinity in circa-2020 America? If you’re Teddy Wayne, you revisit the 1990s. Wayne’s latest novel, Apartment, is centered around two graduate writing students at Columbia University in 1996, but it’s also very much about the current state of American politics. And while it’s not the only high-profile recent novel to use the past as a discussion point for the nation’s present and future — Dexter Palmer’s Mary Toft also comes to mind — Wayne pulls off the impressive trick of making the recent past feel fresh.

It’s also part of Wayne’s ongoing effort to turn a dissection of toxic masculinity into the stuff of compelling drama. Both Apartment and Wayne’s previous novel, 2016’s Loner, center around disaffected young men who end up making terrible decisions — albeit in very different ways. But all of Wayne’s novels to date have focused on young men of varying ages, including 2013’s The Love Song of Jonny Valentine, whose protagonist was a Justin Bieber-esque pop star. His last two represent a departure for him, and it’s something he’s acutely aware of.

“In my first two books, the characters were much more likable, even lovable, and I made things a little bit easier on myself by doing so,” Wayne tells InsideHook. “I think I’ve just become less concerned about that, as I’ve gotten older.”

For Wayne, that means opting for a different relationship with his protagonists. “I view the character less as an alter ego of myself,” he says. “Therefore, I don’t need to curry favor with the reader quite as much, but just write a character who interests me.”

There are a number of reasons why Apartment is set in the 1990s, but one of them deals directly with its setting. Wayne notes that the timeframe allowed him to “show a friendship where the terms were always physical and in person, as opposed to mediated by a screen.” The apartment that gives the book its title is an illegal sublet in New York City’s Stuyvesant Town where the narrator lives. There’s a spare bedroom, which he offers to Billy, a fellow student in the MFA writing program at Columbia University. Over the course of the novel, this arrangement complicates their friendship in myriad ways.

In Apartment, Wayne allows the contrasts between the two men to emerge gradually. The narrator comes from a relatively privileged background, while Billy’s origins are more working-class. Billy is outspoken while the narrator is more closed off. And Billy’s politics are somewhere to the right of the narrator’s.

These differences play a large part in shaping the dynamic at the heart of the book. Some of that dynamic is also shaped by the narrator’s own slow-burning search for a distinct identity, which is reflected in the manner in which the book is told. “It’s a retrospective narration; he’s trying to recreate the effect of what he was like back then,” Wayne says. “And so my thinking is that the narration is a record of what he would be feeling and thinking at the time, which is to say quite repressed.”

Apartment uses its two main characters to explore a number of societal and political questions, something Wayne also chalks up to the year in which the book opens. “It was the last time I could plausibly bring together a coastal liberal — in the form of the narrator — and a Heartland economic conservative like Billy and have them be friends and also possibly have the conservative guy be in an MFA workshop at Columbia,” Wayne says.

“It’s harder to imagine a George W. Bush-era conservative in the MFA program,” he adds. “It’s nearly impossible to imagine a Trump supporter being enrolled in the fiction program and not being completely alienated.”

“It was the last time that the polarization of the country was not so vast as to permit a connection between these two guys,” Wayne says. And in the characters of the narrator and Billy, Wayne also illustrates two distinct takes on masculinity, each one flawed in its own way; each one seeking some sort of completion.

Both of Apartment’s main characters have flaws and sympathetic traits in a kind of balance. That exists in sharp contrast to Wayne’s previous novel. One of the more chilling elements of Loner is the slow realization that narrator David Alan Federman, a student in his first year at Harvard, isn’t the socially awkward young man navigating a crush he first presents himself as. Instead, he’s a potentially sociopathic individual with a nauseating penchant for manipulation and an outsized sense of his own entitlement.

“In Loner, he’s a classic textbook case of the ill effects of toxic masculinity despite being an obvious beta male. He’s reacting with bitterness and anger and resentment toward women.” Wayne argues that the unnamed narrator of Apartment occupies a different position. “This guy is different and is not quite as violent or aggressive, but he’s dealing with his own pressures of masculinity in an unhealthy fashion.”

Though the narrator of Apartment shares some qualities with David — including a talent for resentment and enrollment at an Ivy League university — his flaws lead him in a much different direction. “He himself is this deeply anonymous person, or he feels he’s anonymous or unseen or invisible, somehow,” Wayne explains.

“There’s an implication, too, that he probably won’t have children,” he adds. “He’s also severed from his own father. So he’s kind of a nameless person in society, despite having various privileges. I felt that I could underscore that by not giving him a name that we know. ”

For all that Apartment is about the bond — sometimes rigorous, sometimes frayed — between two men, the fact that it’s centered around the act of writing means that Loner could probably have worked almost as well as an alternate title. “There’s a line in the book early on about how, of everyone [the narrator] knows his age, he’s spent more time alone in his apartment than anyone else,” Wayne says.

It’s a way of life Wayne understands well. “I don’t think was probably the most true for me, but I also think when I was 25 and had not yet gone to grad school, that may have been the case,” he says. “Given that I was working doing internet-based editing and writing jobs from home, I was not really going out into the world as much as my peers were, making their way through the normal professional rungs. I do think that isolation informs this book quite a bit.”

Wayne has used period settings before as a means of exploring the present day. “In Kapitoil, my first book, it was the same thing — it was set in 1999, and was very much about-9/11 politics without ever getting there,” Wayne says. “I like that idea of misdirection and looking at what led to these conditions, rather than the conditions themselves.”

And for Wayne, the ways in which masculinity can turn toxic are impossible to pry away from the larger socioeconomic and political questions of the day. He refers to his novels as focusing on “themes of loneliness and life under capitalism.”

How so? “[They] are very much about class or about ambition or about success in some way and how that affects us in terms of our ability to connect with others,” Wayne says. Toxic masculinity doesn’t come from nowhere, and Wayne’s fiction meticulously explores both its origins and its effects.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.