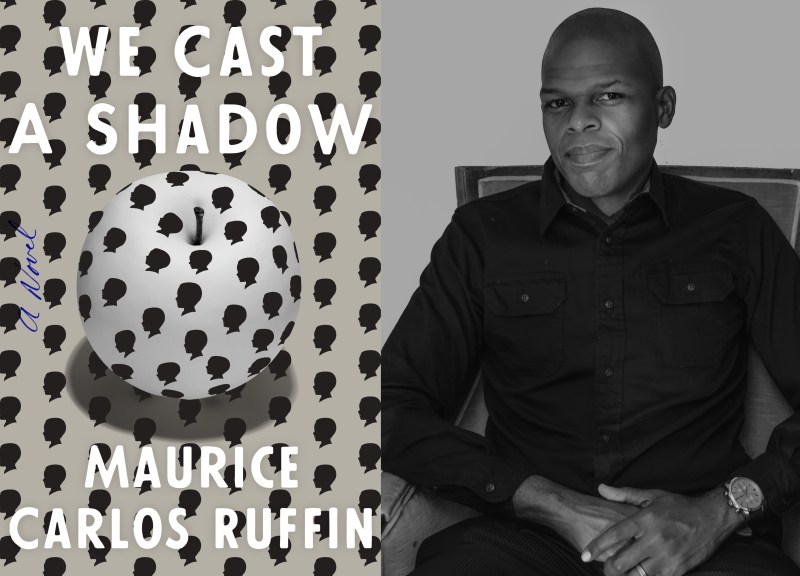

Welcome to Chapter One, RealClearLife’s conversation with debut authors about their new books, the people, places, and moments that inspired them, and what makes their literary hearts sing.

Somewhere in the South, some time in the future, there exists a biracial couple composed of a black man (our protagonist) and a white woman who have a seemingly-all-white son—aside from the dark, slowly expanding birthmarks scattered across his body. Those “stains,” as the narrator so heartbreakingly refers to them, are one of his little boy’s telltale African attributes. In We Cast A Shadow, racism has reared its ugly, othering head to new extremes; despite the past presidencies of both Barack Obama and an unnamed black woman. Predominantly underserved African American communities are literally fenced off and kept separate from the rest of society, nine in 10 black men are or have been incarcerated, most never finish school and there are innumerable laws put in place to keep it all this way. The narrator’s climb to the top of a law firm is, then, a near-miracle. But his road was paved with harsh racism, constant instances of embarrassing humiliation and belittling; a life he doesn’t want for his young son, Nigel. And in this future world of author Maurice Carlos Ruffin, there are advanced medical procedures available to make this disappear—for a price. That includes a full-body “demelanization” procedure that can transform a black person into a white one. It’s a terrifying “fix,” and the only way the narrator believes he can protect his child.

RealClearLife: Was there any particular moment in the past few years that helped spark the inspiration for We Cast a Shadow? It has such charged emotions behind it that feel relevant to so many of the race issues this country has been dealing with both recently and across history, even.

Maurice Carlos Ruffin: I think I’m like a lot of people watching what has been going on in recent years, but the turning point for me was when Trayvon Martin was killed. This man I knew and respected said he felt like Trayvon got what he deserved. It made me think about what it means to be somebody’s father or mother or just a son and feeling the need to protect your family. I’m not a parent but mine did the best they could to take care of me.

RCL: So do you see the book as something that pulls from reality or is it more a satirical piece?

MCR: I was thinking about the isms [when plotting the novel]—like racism—and how hard it is to take care of those you love and shield them from it all. I do consider the book a work of satire but the funny thing is that “satire” is a very slippery slope and that word is in the eye of the beholder, in a way, because you’re pointing out things that are ridiculous but also true.

RCL: The idea of “demelanization” is so extreme and so upsetting in the way it shapes the lives and relationships of the book’s central family. Where did that term come from?

MCR: The term demelanization, I guess it was born of white supremacy and the encouragement of black people to be whiter; like straightening your hair or being forced to cut it off, it happens all the time. I, personally, never felt like I had to change my appearance to not look black but for many people who have Afro-centric hair styles, just as an example, that pressure is there.

I feel like the book starts a conversation and I’m hoping that people who have a set idea about race read the book. I hope it makes them question their own assumptions, read other books and then look internally and ask questions of their own believes.

RCL: There are hints in the book that it takes place some time in the future. Is this a world in which Barack Obama was President?

MCR: I thought about the fact that we had an African American president and it was seen by some as a great turning point in history that “solved” racism and racial problems, but what I came to understand in my research for the book is that racism runs in cycles. I believe that people who lived through the Emancipation Proclamation and then the Civil Rights Era in the 60s kept thinking that the problem of racism was finally over and “fixed.” So, in my book it’s years and years after Obama was President and we’ve reverted back yet again.

RCL: Another one of the book’s ambiguities is where it takes place; it’s only ever called the “City,” though there are hints that it’s somewhere in the South. Did you have anywhere in particular in mind while writing?

MCR: The “City” is definitely New Orleans-influenced. It would be impossible for me to write this without incorporating details from there, like the streetcar. Beyond that, I think that I wanted to give the story a certain level of freedom instead of giving it a name that would make it specific to one place because the idea is that this could be anywhere, at any time in America.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.