James Patterson will never forget the first time he heard The Beatles.

“I was in high school and I was driving to school in this old Rambler. A bunch of kids were riding with me, and the DJ came on. This New York City DJ. And he said, ‘There’s this band that’s really hitting it big in England. They’re trying to make it over here. I’ll play the songs, but they’re not gonna make it.’ And then he played ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ and ‘She Loves You.’ And we’re in the car going, ‘I don’t know man, they sound pretty good to us.’”

A few years later, Patterson got thrown out of a bar for hijacking the jukebox.

“I was in college and I don’t know what my state of mind was, but I played ‘I Am the Walrus’ like five times in a row,” he laughs. “They kicked me out of the friggin’ bar when they figured out I was the one who kept playing it.’”

It’s a Friday afternoon and we’re speaking over the phone about his new book, The Last Days of John Lennon (Little, Brown and Co.). As Patterson looks out the window of his home office in Palm Beach, he beholds the bridge that connects his house to the one next door, a property previously owned by Lennon and Yoko Ono. They were renovating it when Lennon was killed.

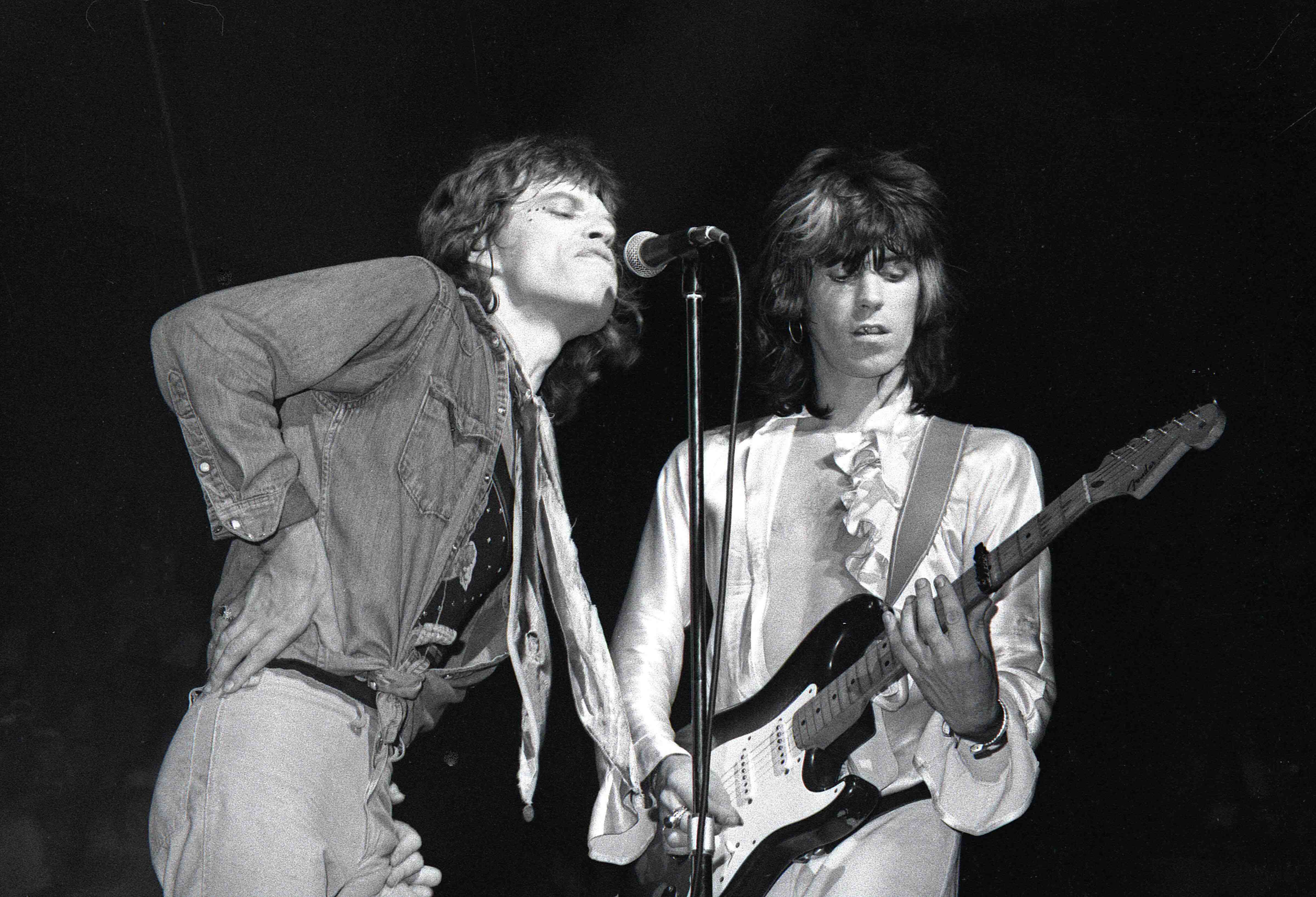

Something most readers might not know about one of the most famous writers on the planet is that he’s a rock-and-roll junky. Patterson attended Woodstock and worked as an usher at Bill Graham’s Fillmore East. He paid his way through college by moonlighting as an orderly at McLean, a psychiatric treatment center north of Boston. One of the patients played original songs on his guitar in the cafe a few times a week. The kid wasn’t famous, but he was good.

“He’d sit there and he’d be singing ‘Fire and Rain’ and ‘Sweet Baby James’ and a lot of the songs that wound up on that first album,” Patterson recalls.

That patient — James Taylor — would become a household name when Apple Records, The Beatles’ label, released his self-titled debut on December 6, 1968. Twelve years later to the day, Taylor had an unnerving encounter in New York’s 72nd street subway station.

“A creepy, sweaty guy recognized me and got in my face,” he later said. “He was talking fast, telling me about himself — that he was working on a project with John Lennon. I had spent nine months in a psychiatric hospital, and it seemed to me that he was mentally ill.”

Two days later, on December 8, 1980, the same man, later identified as Mark David Chapman, murdered Lennon as the former Beatle returned home from the studio to kiss his five-year-old son goodnight. Patterson was living a few blocks away from Lennon’s building then. Upon hearing the news, he walked to The Dakota to grieve with a crowd of broken hearts.

The Last Days of John Lennon, which Patterson co-wrote with Casey Sherman and Dave Wedge, was published on the 40th anniversary of Lennon’s death. Sherman and Wedge, award-winning journalists, did the bulk of the research and wrote the first draft before Patterson took the helm and charted a different course.

“They wanted the book to be more Chapman-Lennon, Chapman-Lennon,” Patterson says. “I just didn’t feel Chapman was interesting enough to deserve the spotlight. He’s a one-dimensional kind of kook. I decided I really wanted to tell The Beatles’ story.”

The book’s title is somewhat of a misnomer. It’s not simply a pulpy account of Lennon’s death — sure, that’s the climactic scene, but the scope is much broader. Patterson chronicles Lennon’s life and the history of The Beatles in a gripping present tense, separating it from the other hundreds of books on the well-trodden subject matter.

“A lot of those books are done by music journalists. They want to be objective and create distance,” Patterson says. “I don’t. I want to be intimate. I want to jump right in there. I want you to feel riding in that cab with Chapman coming in from the airport. Feel that maniac.”

And we do. Patterson puts us inside the killer’s deranged mind. He takes creative license, but his rendering of Chapman’s words and thoughts achieves a chilling verisimilitude. Patterson credits Norman Mailer’s The Armies of the Night as the precedent that empowers nonfiction writers to invent dialogue as long as it feels real.

But Chapman is not the book’s most compelling element. Its page-turning quintessence — like all of Patterson’s work, Last Days… is a page-turner — lies in the stories it tells about the world’s most famous rock band, and especially those of its most inscrutable member. The short, pulsing chapters come and go like movie scenes. Even readers who think they know everything about the Fab Four will appreciate the access that Patterson’s narrative approach offers.

In 1957, we’re sitting by the piano in St. Peter’s Church where a 15-year-old Paul McCartney tries desperately to impress the coolest kid in Liverpool, an enigmatic 17-year-old named John. In ‘64, we’re in a suite at New York’s Hotel Delmonico, where Bob Dylan’s jaw drops upon learning that The Beatles have never smoked weed. Next spring, we’re at a dinner party in London. John, George and their wives get up to leave when their host, John’s dentist, informs them that the coffee they just drank was dosed with LSD.

Scenes like these are sprinkled throughout the book: epochal Beatles’ lore that won’t surprise diehard fans but inject vitality into the narrative. Patterson’s focus on the later chapters of Lennon’s life, however, offers a fresh perspective. He’s particularly interested in exploring the love story between Lennon and Ono.

“People incorrectly blamed her for breaking up The Beatles,” Paterson says. “I think John was just ready to move on. He wanted to make more serious art. He was always inclined that way, and I think that’s why he chose to be with Yoko. I think that John’s the reason the band broke up. Not Yoko.”

Patterson’s assertion pushes against popular fan theories around the band’s dissolution. Ono bore the brunt of the blame at the time — and faced a slew of racist and misogynistic attacks — and when it was clear The Beatles were over, McCartney shaped the narrative by being the first one to publicly quit. But after interviewing McCartney, Patterson is convinced he never truly wanted to leave the band.

“I think he misses John. I think he loved John. I get the sense with Paul that if he could, The Beatles would still be together,” Patterson says. He pauses, then quips, “And he’d be running it.”

The extent to which Ono catalyzed Lennon’s growth as an artist and a man is one of the book’s central themes. She presents not as a smothering succubus, but an enlightened, forgiving partner. When Lennon started behaving poorly in the mid-’70s, Ono sent him to L.A., gave him a hall pass to date their 23-year-old assistant and told him not to come back until he sorted himself out. This turbulent period in their relationship, which they later referred to as John’s “lost weekend,” lasted a year and a half.

When Lennon returned to New York, he had grown up. He stepped away from music to focus on raising their son Sean. Patterson casts this older, more paternal Lennon in a redemptive light, a man determined to atone for being an absent father to Julian, the son he had in 1963 right as The Beatles exploded. He doted on Sean, cooked macrobiotic meals for the family and, just like many covid quarantiners, dabbled in breadmaking. Ono, meanwhile, pursued breadwinning. She grew their wealth by executing a series of shrewd real estate transactions and threw in some speculative cattle trading for fun.

“Only Yoko,” Lennon told Playboy, “could sell a cow for $250,000.”

As the calendar flipped to 1980, Lennon was in the best physical and mental shape of his life. His house was in order and he was bursting with creative energy. He started recording music again. In November, he and Ono released Double Fantasy, a simple yet beautiful portrait of domesticity and love. One month later, he was murdered.

Many writers have explored the major storylines of this crime: its cultural-historical magnitude, the acute pain felt by Lennon’s family and fans, the ugliness of his killer. Patterson covers all of these bases, but his commitment to narrating his subject’s final years offers something else. Perhaps ironically, it’s the world’s most prodigious crime writer whose telling of the story reaches beyond the mere crime to illuminate the more heart-wrenchingly human layer of the tragedy: that a man’s life was stolen at the precise moment he figured out who he was.

The whole book is wired with an undercurrent of cultural commentary. Lennon loved America, but, much like the 19th-century diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville, his perspective as a foreigner gave him fresh eyes to scrutinize American society. Something he perceived early on is that this is a uniquely violent country. It wasn’t just the guns (though our sacrosanct attitude towards them terrified and confused him); he also warily observed the spirit of frontier violence that had grafted itself to the nation’s DNA in its formative years and evolved ever since.

In 1966, Lennon made a passing comment to a British journalist that The Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.” Nobody thought twice about it. But then the interview was reprinted in an American teen magazine and people went crazy.

“I don’t think he was bragging,” Patterson says. “I think he was going, ‘Isn’t it absurd that we, these working-class musicians, are more popular than Jesus?’ But after that remark, their lives were threatened. You know how it is. We like to threaten peoples’ lives here.”

In a much lighter way, Patterson can relate to Lennon’s Jesus controversy.

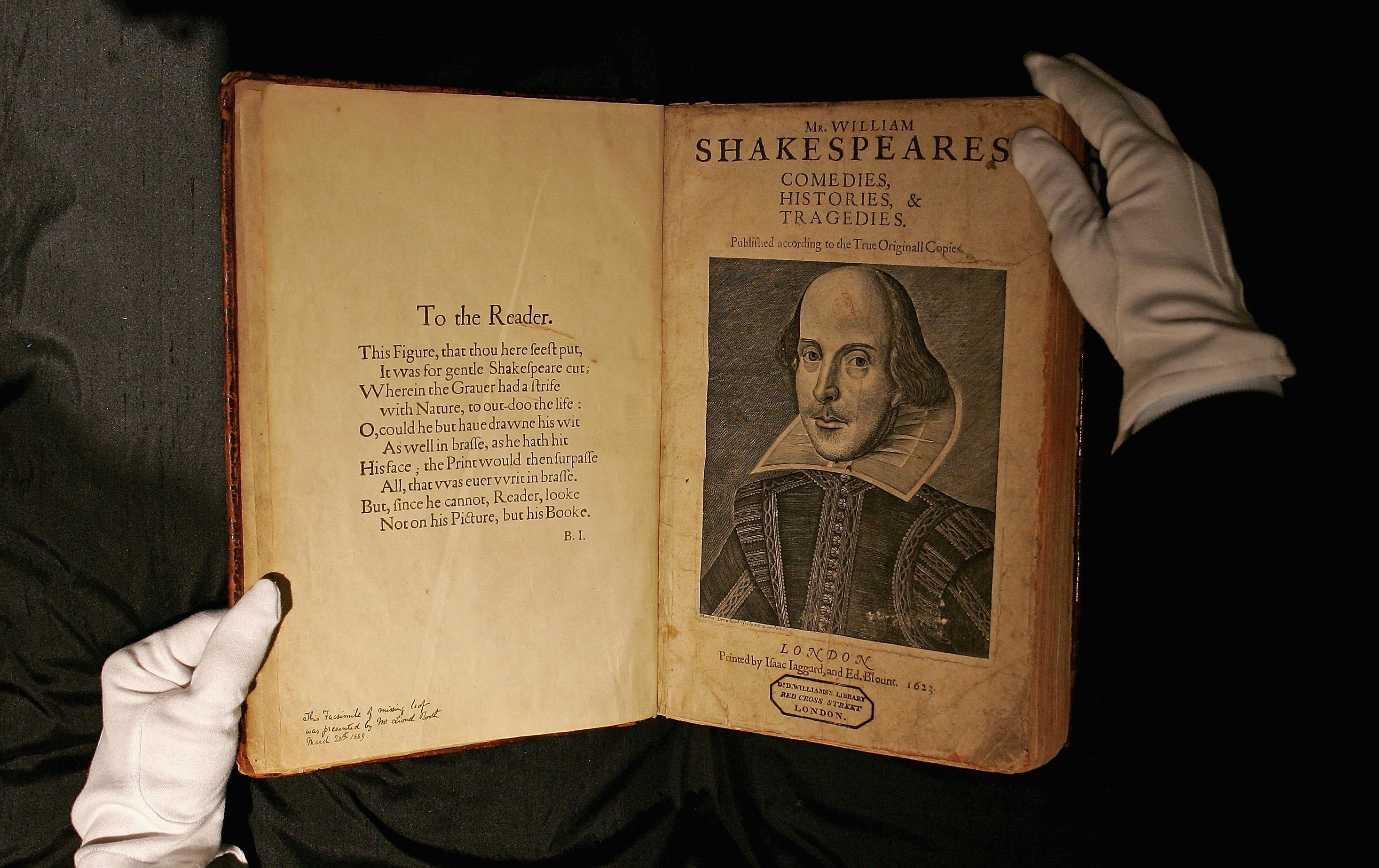

“A few years ago, [a publisher] wrote a thing that I was more popular in England than Shakespeare,” he says. “And I’m like, ‘Are you guys shitting me? That’s ridiculous! Do you guys even read Shakespeare? Do you read my stuff? He’s your guy!’”

Patterson does not lack self-awareness. He knows he’s not Shakespeare and he’s never pretended to be. And yet, there are legitimate comparisons one could make between the two. And Lennon for that matter. All three are known for their relentless work ethic, prolific output and outrageous commercial success. Since leaving his advertising career to pursue writing, Patterson has published 275 books, selling some 425 million copies.

There are only a handful of blockbuster authors whose books transcend generational tastes, seamlessly captivating sons, fathers and grandfathers at once. How does Patterson explain his broad appeal?

“Because I’m so good looking,” he deadpans. “I don’t know. I tell stories. A lot of authors don’t really tell stories. And I love doing it. I don’t work for a living — I play.”

In recent years, Patterson has expanded the borders of his playground. He still churns out crime novels — in November, he published Deadly Cross, the latest installment of his Alex Cross franchise — but he’s also started writing children’s books and nonfiction.

We’re currently living in the golden age of true-crime narratives, and Patterson’s nose for compelling stories has led him to the genre’s epicenter. In partnership with his friend Tim Malloy, Patterson helped expose the horrific crimes of Jeffrey Epstein. Their 2017 book, Filthy Rich, was turned into the wildly popular Netflix docuseries, which Patterson executive produced. He’s also written a book about Aaron Hernandez.

But Patterson’s foray into nonfiction is not limited to true crime. He’s tackled The Kennedys, Muhammad Ali and the 2016 presidential election. Where some writers are daunted by the saturated coverage of historical events and characters, Patterson feels liberated.

“That’s the weird thing about nonfiction,” he says. “Take Shakespeare. We don’t know anything about Shakespeare. There’s like a page from some trial where he’s involved. We know where he was born. We know that he was married. We know that his name is on a lot of plays. That’s it. And yet, there are like 200 biographies on him!”

No matter how many books have been written about a subject, there’s always room for one more — as long as the writer can tell a new story. In The Last Days of John Lennon, Patterson and his co-authors do.

They also manage to convincingly humanize a subject that has long since ascended into the ranks of the immortal. As I read the book, I couldn’t help but think of what Shakespeare’s most famous protagonist tells his friends when they shower praise on his recently deceased father.

“He was a man,” Hamlet says. “Take him for all in all. I shall not look upon his like again.”

The same could be said for John Lennon.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.