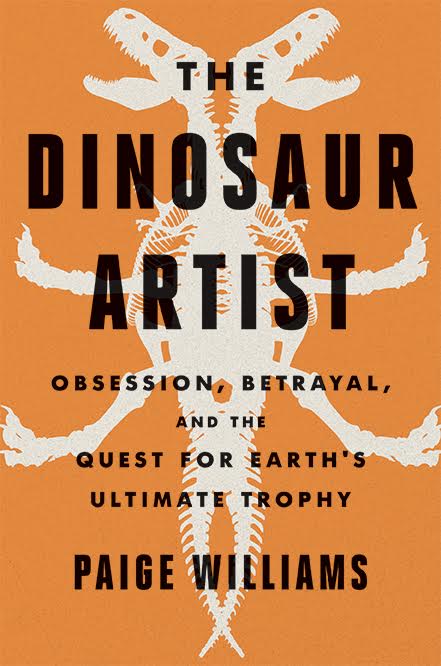

Dinosaurs are one of the great human connectors—this much is clear in Paige Williams’ recently published book, The Dinosaur Artist. From the time we are children, we marvel over dinosaur skeletons and teeth, imagining an Earth dominated by lizards as tall and as long as skyscrapers. Our planet’s oceans hold secrets too, of gargantuan prehistoric sharks and crocodiles that could decimate an apartment complex in a few bites. But perhaps most fascinating is that, for all of their mass and might, these titanic reptiles were wiped out 66 million years ago after an asteroid slammed into Earth, setting off a chain reaction of catastrophes that wiped out their population across the globe.

If they couldn’t stand a chance, how can we? And do their secrets have anything to tell us, so that we may avoid a similar fate should another asteroid come for us?

The Dinosaur Artist peers into the human curiosity that hangs on that question—as well as the lengths and laws we’re willing to travel and break in our journey. Specifically, it looks at what is perhaps one of the strangest court cases in history: United States v. One Tyrannosaurus Bataar Skeleton. The case centered on said Tyrannosaurus skeleton, which was illegally imported to the United States from Mongolia. According to Mongolian Constitution, all dinosaur fossils by law belong to the country’s people—but that didn’t matter to fossil hunter Eric Prokopi, who attempted to sell the skeleton for more than $1 million. Prokopi, who had curated private collections for the likes of actors Nicolas Cage and Leonardo DiCaprio, was ultimately jailed for 3 months and gave up all claims to this skeleton, as well as others he was charged for illegally possessing.

RealClearLife recently caught up with Williams for a Q&A to talk about this bizarre case as well as who should be allowed to own fossils, why it’s important, and what secrets they may hold for humanity at large.

RealClearLife: Do you think the public deserves more of a say in how fossils are excavated, and where they end up (e.g., scientists v. fossil hunters, private collections v. museums)?

Paige Williams: There’s a strong argument for leaving science in the hands of scientists, and for developing a system that better safeguards the only remaining evidence of the planet’s history. There’s also an argument for enlisting non-science professionals, many of whom are field experts, in the careful cultivation of paleontological resources. The latter would say that part of what motivates them is the notion that careful hunters should gather available fossils instead of letting them weather out, at which point they’re no good to anyone—there simply aren’t enough paleontologists to pick up or excavate everything that’s out there. The public has always played a vital role in paleontology (unlike in other scientific disciplines) because without the casual hunter, or the hobbyist, or the commercial hunter, the science might not exist. Natural history museums certainly would not exist. Any good paleontologist would acknowledge that the science needs eyes out there, all over the world, looking for the fossil remains of life on Earth.

RCL: What’s your favorite dinosaur?

PW: I mean obviously Tarbosaurus bataar, followed closely by its North American cousin, T. rex. How clichéd is that? Despite the theories about scavenging, it would be hard to convince me that rex—or any animal with foot-long teeth—wasn’t an apex predator.

RCL: If private fossils hunters were eliminated, what do you think the impact would be on new discoveries made?

PW: More eyes on the ground means more finds. Without a global community of fossil hunters, the fossil record would without question contain far fewer species. It was “amateurs” who made some of the greatest and most pivotal finds. Without the non-scientist hunter, we’d know far less about the planet’s history than we do, including when and where certain creatures lived, and how they behaved, and when and why they went extinct. Before the word science ever existed, natural philosophers were walking around, picking up strange objects, and wondering what forces of the universe had created them. If fossil lovers weren’t allowed to be curious, and to contribute to the fossil record, we as a society would be far the poorer in our understanding of everything from geology to evolution to climate change.

RCL: What are the dangers of allowing private fossil hunting to continue?

PW: Paleontologists worry most that potentially important scientific specimens, the ones that might unlock theories about, say, prehistoric environments or animal growth patterns, will be destroyed by careless hunters or disappear into private collections, never to be studied. A great many private or commercial fossil hunters care deeply about the specimens they collect—the best of them collect data in the same way that paleontologists do. It’s the poachers—the venal, destructive lawbreakers—that worry the scientists and the honorable commercial hunters alike.

RCL: Why are people paying so much money for fossils?

PW: Because they can?

RCL: In your research, did you find that it’s more of a Western thing that we believe that we’re entitled to fossils (the finders-keepers mentality, as well as the collecting of fossils)?

PW: The finders-keepers idea plays out uniquely in the United States. No other country allows hunters to keep whatever dinosaur bones and teeth (or other fossils) they find on their own property, or on land where they have permission to collect. Public lands are off limits—it’s illegal to collect most fossils on federal property, such as the national parks. The concept of finders keepers seems to have appeal around the world, though.

Commercial hunters like to argue that the Earth belongs to everyone, and therefore that they should be allowed to hunt fossils without restriction, whether dinosaurs or dragonflies. It’s a convenient and faulty construct, as is one particular legal notion that surfaced during the federal T. bataar case involving the subject of my book: that countries cannot legislate natural resources that predate borders and laws. As one of the sources in my book puts it, “That’s like saying the Saudis aren’t entitled to their oil.”

RCL: Can it be quantified what is lost when fossil hunters excavate without using a scientific method (i.e., contextual data that could help understand a changing climate)?

PW: Hunters who yank fossils out of the ground do a grave disservice to science because they destroy information that provides clues to the history of life on Earth. Rogue excavations have been compared to removing a homicide victim from a crime scene without logging the kind of data that might help an investigator solve the case.

In the case of fossil dinosaurs those questions would include: Where and when and under what circumstances were the bones found? How deep? Which bones were present? In what pattern? If there’s a skeleton, was it intact? Was other fossil evidence present, like other animals? How about plants? Were there bite marks? Evidence of bone breaks? Hints about offspring? Hints about weather? The data surrounding a fossil are numerous and altogether vital to understanding life and its place—and, in turn, our place—in the planet’s history. And the window of opportunity is finite: Once a fossil is out of the ground, there’s no going back and recreating that all-important opportunity to capture the facts as they existed at the time of discovery. When the work isn’t done right, the loss is unquantifiable.

RCL: Can you talk a little bit about the positives and negatives of Jurassic Park as this iconic cultural touchstone. Has it inspired people? Has it encouraged more collecting? How has it affected prices of dinosaur fossils?

PW: It isn’t a stretch to say that Jurassic Park stoked people’s interest in these fascinating animals. It’s been said that the film did for dinosaurs what Jaws did for sharks. To what extent that global interest benefits science: good question. What we do know is that dinosaurs are what Kirk Johnson, the paleobotanist who leads the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, calls a gateway. He once told me, “Dinosaurs are the gateway to science, which is the gateway to technology, which is the gateway to the future. I can make a case that paleontology is as significant as anything in this world because of its ability to get kids into science.”

RCL: What do you think is the major takeaway for affluent collectors who want to ethically acquire fossils? Is that even possible to do?

PW: The paleontologists who most despise the commercial fossil-hunting world and who truly believe the trade endangers science would say that it’s straight up unethical to collect fossil vertebrates like dinosaurs. They can abide the collection and sale of, say, ubiquitous materials like shark teeth; but it horrifies them to see the trafficking of bones. A collector can avoid feeding the black market in particular in a couple of ways: one, do the homework; two, don’t buy dubious fossils. Any paleontologist or legitimate dealer would be happy to explain how to self-educate, and how to collect with integrity.

RCL: Anything you think a prospective reader should know before delving into your book?

PW: It’s a story with multiple threads: science, history, the history of science, craftsmanship, class warfare, post-Civil War industrialization, black markets borne of major shifts in global politics. Oddly enough, all those threads came together in the story of this one Gobi Desert dinosaur—a story that likely never would’ve come to light if the skeleton hadn’t sold at auction, in New York, for over $1 million. Dinosaurs always appeared to be time capsules; I had no idea.

Find The Dinosaur Artist at Barnes & Noble or on Amazon.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.