I was 13 when Friends premiered on NBC. I didn’t get it. Why were they so cheerful? How did they afford those New York rents? Why was I so attracted to Chandler’s supposedly annoying on-and-off girlfriend, Janice? The only reason I knew anything about the show at all was simply because of timing: it came on before Seinfeld.

Seinfeld was my introduction to more “adult” sitcom fare. I put adult in quotation marks because it seems most sitcoms are aimed generally at people 18 and up, but I got hooked because Seinfeld felt like it was offering something different. What exactly that was my teenage mind couldn’t make out, but I figured it was somewhat heady since older, cooler people I knew that watched the show talked about the plots as if they were highbrow indie films you had to drive to the city to see. It was comedy, but it was a little smarter, a little more out there; you either liked it or you didn’t, the same way people felt when they first watched early Letterman or current-day comedians like Chris Gethard and Eric Andre. It didn’t necessarily make you laugh, but you knew it was funny.

Of course, you couldn’t have Seinfeld without Larry David. You’d have Jerry Seinfeld, but that was about it. His standup wasn’t enough to make a world-changing television show. David, as we’d learn, pretty much was the walking, talking Seinfeld universe. And of all the shows I watched on my first 18 years on this planet, I feel fine saying none besides The Simpsons had as much of a big impact on me as Seinfeld. Both shows shaped my sense of humor, and as is often the case with those born on the other side of the 20th century, my worldview. I want the big salad. You got a question? You ask the 8-ball. They’re real and they’re spectacular. Yadda, yadda, yadda.

Esquire used to do this thing, back when people actually picked up magazines and the power of an article could transmit from paper to popular conversation without algorithms or a person with 100k Twitter followers boosting it out into the world. They’d occasionally get a writer to sum it all up, to talk about their generation. F. Scott Fitzgerald tackled the 1930s, noting, “It is important just when a generation first sees the light.” William Styron took on the ’40s. Those are both great, but I really love David Leavitt trying to make sense of his particular cohort of Gen-Xers, the kids who grew up after the ‘60s and before the ‘80s, the black hole of youth that was the 1970s. He does a particularly good job summing up the feelings of not exactly belonging to a generation, because, frankly, the idea that you have that much in common with somebody born 10 or 20 years after you is silly.

“We hit our stride in an age of burned-out, restless, ironic disillusion,” Leavitt wrote. “With all our much-touted youthful energy boiling inside of us, where were we supposed to go? What were we supposed to do?”

I was four when that was published in 1985. I didn’t read it until about 25 years later, almost at the exact same time when Doree Shafrir wrote an article for Slate about people in the age group she and I share, defining those born during Jimmy Carter’s administration as being “too young to claim Singles and Reality Bites and Slacker as our own,” and that while “the proud alienation of the Gen X worldview doesn’t totally sit right, we certainly don’t yearn for the Organization Man-like conformity that the Millennials seem to crave.” In essence, we were at odds with any generational label assigned by writers and researchers.

I won’t disagree with that idea, but I’ll also take it a step further. I’ll say that one of the defining characteristics of people in my particular age group is some ingrown obsession to sub-categorize things. The piece itself even brings up an idea floated by a Teen Vogue editor to start calling our “micro-generation” by something like “Generation Catalano,” a tribute to Jared Leto’s character from My So-Called Life from long before he was in some horrible band or strolling up the Met Gala red carpet with his severed head in hand. I get the sentiment, but, again, I wasn’t really watching My So-Called Life in the mid-1990s; I was watching Seinfeld.

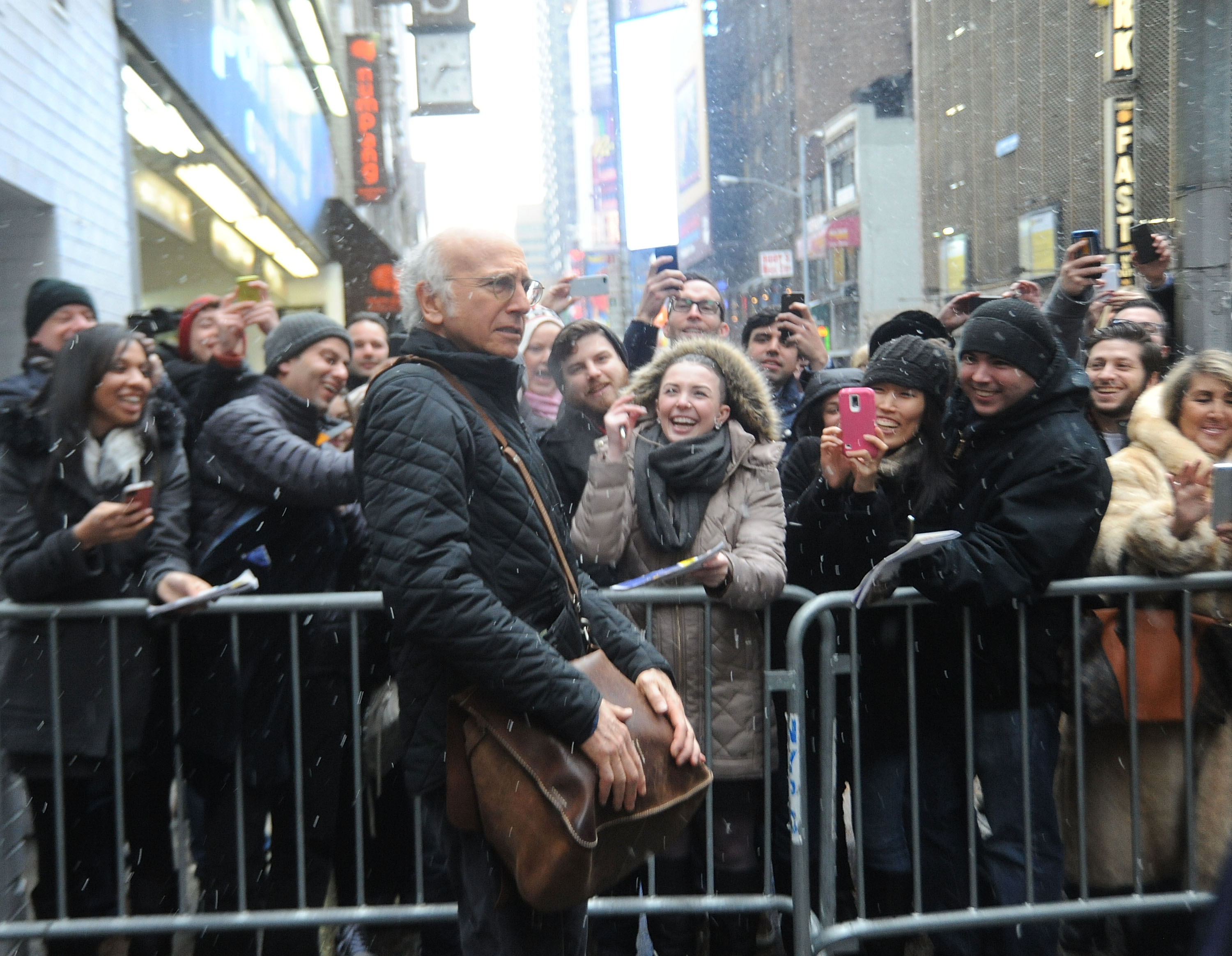

I feel like, if anything, I’m more a part of the Larry David Generation. The bulk of the comedy I have enjoyed over my adult life, and the way I tend to feel about the world around me, can connect back to David in some way or another.

The great thing is that you don’t need to have been born during any specific time to be part of the Larry David Generation — you’re currently living in it. The only requisite for membership is whether you embrace that or not.

The key to David’s comedy working so well, people will remind you, is awkwardness. But that awkwardness has to come from somewhere. David’s Larry David character (I don’t believe he’s 100 percent like the person on the show — maybe more like 75 percent), just like the ones he and Seinfeld created, are awkward because they’re accidental outcasts. They don’t dress strange or espouse any specific set of beliefs … they’re just out of step. They have their ideas about how the world should be and pretty much everybody they encounter does not share those beliefs. They don’t fit in simply because they are. It’s hard to pull off during an episode, but once Luciano Michelini’s “Frolic” starts playing before the end credits, I start taking stock of who was wrong and who was right, and the answer I usually arrive at is a collective “Everybody.” We all have the right to hold horrible opinions and ideas of how the world should work (well, not too horrible. Like, don’t be a Nazi), and the people around us are allowed to have horrible reactions to them. That, at its core, is what I’ve come away with from repeated viewings of Curb episodes.

It all has to do with the boom of “cringe comedy” that started to take place not long after the notoriously disappointing Seinfeld finale in 1998 and the 2000 premier of Curb Your Enthusiasm. Many shows were written or created by people in that specific demographic, who could trace their burgeoning adulthood with David’s brand of comedy becoming the norm, or were the ones who embraced it early on because they saw something in all that awkwardness. Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant’s The Office (as well as the American version), It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Veep, The Mindy Project and Difficult People probably couldn’t exist without Larry David. Or, at the very least, they’d all have a harder time finding an audience. Seinfeld softened people to a certain brand of awkwardness, and Curb Your Enthusiasm turned it all up a few notches. Who else but David could make a fight between a Holocaust survior and a contestant on the show Survivor actually work? It would be pure shock value in someone else’s hands, but David knows how to make an absurd situation feel uncomfortably real.

It’s why so much of what Mindy Kaling has done works. She took some of David’s template and applied it to helping shape the American version of The Office, and after that, mixing David’s brand of awkwardness with a reimagining of Nora Ephron rom-coms on The Mindy Project. Likewise, Difficult People, the Julie Klausner and Billy Eichner series that was one of my personal favorites of the last decade, has a noticeable David influence. Two of the most popular shows of the 2010s, Broad City and, yes, Louie, before it and the show’s star, Louis C.K., were canceled, similarly came of age in the newfound niche that Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm had carved out.

The beautiful thing about comedy is that it’s subjective. You and I might meet and you might say, “I’ve got this show that I think is hilarious.” I’ll watch five episodes and won’t laugh once; but I’ll find something else about it I like. Another show that’s part of the Larry David Generation is Fleabag, a refreshing take on the awkward-as-fuck comedy that David made so popular. But where some of my friends got laughs, I found Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s character to be so deeply messed up that I couldn’t help but feel terrible for her; each episode was like a kick in the stomach. Similarly, as the FX show You’re the Worst started to peel back a layer and expose itself as a great study of people dealing with mental illness and not just a show out for yucks, it got even better.

But maybe even more important than his influence on TV over the last 20 years has been the way that David has acted as a balm in these soul-chapping times. Somebody new takes the crown as the worst person in the world on a daily basis; we have more access than ever to seeing just how terrible people can be. Everything is awkward, and David understands how to embrace that. He’s done it so well, in fact, that other comic minds have learned from his example and expanded the genre that he helped create. That’s really what unites those of us who count ourselves among the Larry David Generation. It’s not an age thing; rather, it’s a willingness to be a little more honest. To embrace your graceless behavior.

The real trick is whether you learn anything from it. You’re not Larry David, after all. You’re just living in his world.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.