Mike Massimino is a former NASA astronaut who was part of two servicing missions to the Hubble Space Telescope in 2002 and 2006. He retired with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal and two Space Flight Medals. Currently he is a teacher at Columbia University and a senior advisor at the Intrepid Museum. He is the author of Spaceman: The True Story of a Young Boy’s Journey to Becoming an Astronaut. As told to Charles Thorp.

____________________________________________________________

The morning of launch you have your breakfast with the crew in your housing on the base, where you’ve been quarantined off from other people for a few weeks to make sure no-one is sick before taking off. Everyone gears up and heads to the transport van, which takes you to the launch pad, all while medical staff stays by your side.

Once you are in the shuttle and strapped in, you are just waiting until the rocket lights. Everything is still until that rocket lights. Then you are really going somewhere. You move very abruptly. It is a surreal experience. The shuttle had a combination of liquid-fueled rockets and solid rockets.

The solid rockets go off like sticks of dynamite and they burn a little rough. So there is quite a bit of shaking going on, and then the G-force builds up towards the end of the launch. At first it is hard not to think that something is wrong, with all of that movement, but I could see the veterans on my flight high-fiving, which was the only indication I had that everything was fine.

A lot of your training as an astronaut is about preparing you to solve problems that occur, but there was a feeling that if anything went wrong with a launch, there was absolutely nothing that we would be able to do. It feels like a beast is grabbing you and taking you wherever you were going to go. Right above my head in the shuttle there are placards on the emergency protocols on what to do if we need to bail out or anything like that. But in my head I was thinking, “This is just something for me to read while I’m dying.” But overall the sensation I had when leaving was just being supremely impressed by the power and speed of the craft that we were aboard.

Once the burn is done and we have gotten to where we need to be, the engines cut. All of a sudden everything is weightless and peaceful. Your body starts to rise up into your harness. My very first launch I took off my helmet, put it in front of me, and let it go to watch it float, like I had seen Tom Hanks do in Apollo 13.

I remember the first time I got to look at Earth from space, I was on the mid-deck, unstrapped. I looked at the planet. It was stunning and beautiful, but I have to say you are still inside — inside a space shuttle, but still inside. It is an entirely different animal when you are actually going out for a spacewalk. I would say the difference is like that of an aquarium, if you are outside of the tank, looking at the fish, it may still be amazing. But it is completely different when you put on the mask and actually jump in. You feel like you are engaging with that environment.

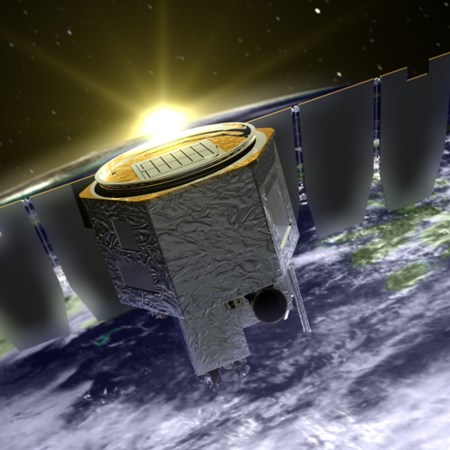

Being on a spacewalk means that you are outside of the shuttle, in your suit, in space, using handrails and foot restraints attached to a robot arm to move around. It is not like a moonwalk, where you are actually walking on a surface. For me, I was doing spacewalks in zero gravity to repair the Hubble telescope.

Our altitude while fixing the Hubble was about 100 miles higher than that of the International Space Station, so we weren’t seeing that same kind of detail. We could see more of the curve of the planet. The planet takes up your whole field of view.

They pair you up with a veteran astronaut when it is your first spacewalk, and I went out with Jim Newman. He went out first to make sure the coast was clear, set up our restraints, and told me to come out. We have gold visors that we can put down to block the sun, but his was up and I could see his face very clearly. He is just there smiling at me like “check this out.” And behind his head was the continent of Africa. I was like, “How am I going to get any work done with a view like that?”

In my head I was thinking, ‘This is just something for me to read while I’m dying.’

I was on that first mission with one other rookie, Duane Carey, who was an Air Force pilot, and because he was the pilot, he wasn’t going to be tasked with going on a spacewalk. Before we launched, he came up to me and said that because he was probably never going to get the chance to spacewalk, he wanted me to tell him exactly what it felt like immediately after I came back in the shuttle.

Right before I went out, before we closed the airlock, Duane came up to wish me luck and then said, “Don’t forget.” When I got back in and we repressed, he was right there in my grill. Getting out of the spacesuit you take your glove off first to alleviate the pressure and then you take the helmet off. I handed my helmet to him, he put it down, and got right back up in my face for the answer.

“Digger you will never believe it,” I said to him. “The Earth is a planet.” And what I meant about that is my idea of what the Earth was had changed. Our whole lives we are walking around and we know this home for what we see, but from up there, you see the chaos, you see it in this infinite black. You are actually witnessing the cosmos in action. There is so much more happening out there than we could ever, ever imagine.

This series is done in partnership with the Great Adventures podcast, hosted by Charles Thorp. Check out new and past episodes on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts from. Past guests include Bear Grylls, Andrew Zimmern, Jim Gaffigan, Ken Burns and many others.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.