Sometimes it occurs to me (often when I see the phrase on a t-shirt, or used as a generational touchstone) that I am the “Yr” of the Sonic Youth song “Kill Yr Idols.” Not only does it brings me a little shimmer of pride, it also reminds me that this is extraordinarily good advice.

The origins of that advice are rooted in my past. And the past is a stranger with whom I share a hard drive. It is a corrupted hard drive, too.

Whole summers are missing, entire arcs of experience have been reduced to fractured zeros and ones, two semesters of college are completely unrecoverable, and the entire unit has a big sticker on it that says, “For Amusement Purposes and/or Self-Loathing Only.”

Nevertheless, the past sometimes sends me postcards.

This postcard tells a story that begins in June of 1982. Jack Rabid, the legendary concierge of punk rock, and I were walking north on the Bowery, and had just made the right turn on to St. Marks Place. We were both 20 years old at the time. We visited St. Marks Place nearly every day, usually landing at a spectacular used-record shop halfway down the block called Sounds.

On the sidewalk on the southeast corner of St. Marks and Bowery, a fellow was sitting behind a blanket that held a strange assortment of possessions. Amidst the toasters, cowboy boots, and 8-track tapes was a bass guitar (a very reasonable Fender Jazz-imitation brand, Carlo Robelli). It cost $100.

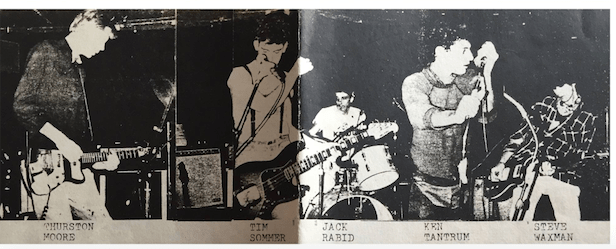

Jack was the drummer in a reputable local punk band called Even Worse. A few nights earlier during a gig at Irving Plaza, Jack’s entire band had quit on him onstage (which would be tragic if it wasn’t so funny). Jack may dispute this account, but my version makes for a prettier postcard.

Jack turned to me and announced, “If you buy that bass you can be in my band.”

The night before I had done a DJ gig at the Mudd Club, so I did have enough cash on me. Despite the fact that I really couldn’t play the bass, I handed over the hundred bucks without hesitation.

As soon as I took ownership of that bass, I was a member of a band.

There is nothing like that first realization that you were now in a band. Why, only seconds ago, you were a normal person who listened to things and argued about B-sides and ate at Blimpies a lot and hoped people would notice that Artaud book sticking out of your backpack. But now, you —yes you — were in a band! You had been reading about bands and seeing bands and listening to bands and fantasizing about bands for as long as you could remember, and now you actually were in one.

In my entire life in the music industry (40 years now, goddamn it), the only thing that compared to that feeling — that fever-on-the-inside/grin-on-the-outside/scream-in your-heart awareness that you were now in a band — was the first time I learned that an act I was working with had achieved gold record status.

I set about teaching myself the rudiments of punk rock bass guitar. I played along, over and over, with the first Ramones record, the first Clash record, PiL’s Second Edition, and the Clash’s London Calling. I did this pretty much for a week straight. I hereby apologize to my roommate at the time (Sorry, Kevin). It did the trick, and honestly, I still recommend this as a way of learning the instrument.

A few days later, Jack and I were walking down McDougall Street, on the way to another one of our standard hangouts, 99 Records. A small but massively amazing import and independent record store, 99 Records also boasted its own, very influential label. As we were approaching the store, a boyish, very tall and very blonde fellow was climbing up the steps out of 99. Jack said to me, “That’s Thurston. I’m going to ask him to play guitar in the band.”

I had some small familiarity with Thurston Moore, since I had seen him perform multiple times as a member of the Glenn Branca Ensemble, and I also knew of his relatively new (and, at the time, vastly under the radar) art-rock band, Sonic Youth.

Thurston did indeed enlist in Even Worse, along with two pals from NYU’s Weinstein dormitory, vocalist Ken Temkin and second guitarist Steve Waxman.

Thurston and I quickly became fast friends. We were both record geeks with a penchant for the more extreme ends of hardcore punk and metal, and we both saw an interesting overlap between hardcore’s grind and the tripping, droning harmonics of avant garde music. We went to a lot of shows together, mostly stuff like Motörhead, Black Flag, Void, Iron Cross, things like that.

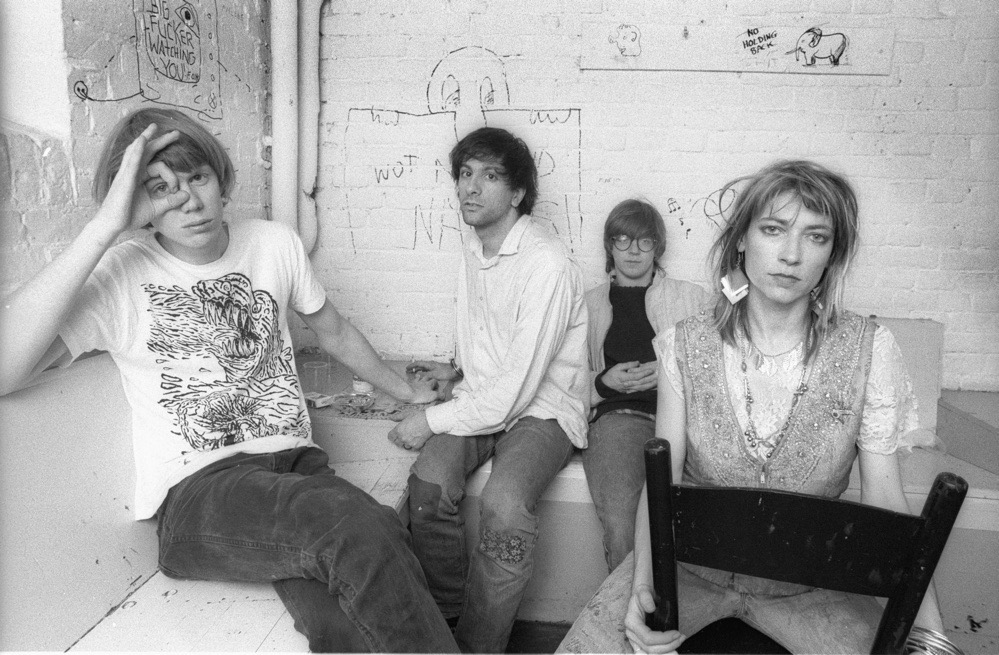

Thurston and his owl-ish girlfriend, Kim, lived in a shattered, smashed corner of the Lower East Side, what was then a no-go zone except for the heartiest and most intrepid pioneers. I remember that their flat was pale blue, long, and trapped between lightless tenement airshafts. They had terribly interesting friends who made odd films and strange, skeletal music. Thurston never seemed to have any money, and since I was actively working as a journalist at this time I would occasionally hire him to transcribe my interview cassettes at the fairly generous rate of ten bucks a side, which seems steep, even now.

Simultaneously with our time in Even Worse, I was writing a great deal for The Village Voice. My editor at The Voice was the legendary Robert Christgau. He was very generous with his time, wisdom, and skill. I would often tell my friends how fond I was of him. This seemed to especially annoy Thurston, since Christgau had given a negative review to Sonic Youth’s first EP.

In their early years (’81 – ’83), Sonic Youth were pretty much the world’s greatest rock’n’roll band. They were a raucous, chanting, shrieking subway-screech meets refrigerator-drone blend of Branca’s apocalyptic, scraping guitar and hardcore punk’s thrash and rumble. Live, their sound was often so feral that it was reduced to nothing more than a gorgeous, courageous, and ridiculous rhythm and noise.

They were also universally pretty unpopular in those years; the contemporary rock critic cognoscenti despised their disorganization and anti-pop, and they usually played in front of tiny audiences. At the time, I was virtually the only mainstream music journalist writing anything positive about Sonic Youth.

Sometime in mid-1983, Sonic Youth debuted a new song called “Kill Yr Idols.”

I remember being startled when I first head it: it began with a woozy, clipped two-chord guitar sequence, the closest thing Sonic Youth had ever recorded to a traditional rock guitar riff. It seemed almost like a rockist parody, but I could tell it wasn’t: Sonic Youth were trying to shoehorn the sibilant, slapping riffs of SS Decontrol, Minor Threat or even AC/DC into their own smothering, steamrolling, lug-nut s**ting sensibility. It seemed like an enormous leap forward for the band.

I was so blown away by this musical development that, bizarrely, I missed what was staring me right in the face in the first verse of the song:

“I don’t know why

You wanna impress Christgau

Ah, let that s**t die

And find out the new goal”

I never talked about this with Thurston or any member of the band, but it was later confirmed by him that the lyric was inspired by, uh, me, and the fact that I had one foot in Sonic Youth’s world and another in Christgau’s sphere.

By early 1984, both Thurston and I were out of Even Worse. He moved on to an unusually credible kind of stardom (the sort reserved for people like Beck or Neil Young), and I moved on to the Glenn Branca Ensemble (where, ironically, I replaced Thurston Moore). Later in 1984, I formed my own avant pop ensemble, Hugo Largo — which was inspired by the idol-killing spirit of Sonic Youth, Swans, and PiL, but sought to shatter glass with whispers instead of screams.

Mind, you Sonic Youth were not using the phrase in any heavy duty philosophical, cosmological, or spiritual context, but it does totally work in that fashion. As Thich Nhat Hanh wrote in his adamantine exploration of The Diamond Sutra, The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusion:

“Then the World-Honored One spoke this verse:

Someone who looks for me in form

or seeks me in sound

is on a mistaken path

and cannot see the Tathagata.”

Yeh. Kill Yr Idols.

I thank Thurston and Sonic Youth not only for making me the ‘Yr” in one of their trademark songs, but also for helping teach me that idol killing, when done with as much joy and as little pretension as possible, is a beautiful path to creativity.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.