If you ever fall down a Wiki well searching for the origin of musical diss tracks, you’ll inevitably learn about Lolita Shanté Gooden. In 1984, the 14-year-old from Queens adopted the stage name Roxanne Shanté and recorded a song called “Roxanne’s Revenge.” Spewing ingenious lyrical bile, Shanté eviscerated “Roxanne, Roxanne,” a song by the Brooklyn hip-hop trio UTFO. Within weeks, UTFO answered with a new single, “The Real Roxanne.” After that, the levees broke. More than 30 Roxanne songs came out over the next year as other artists dove into the hot beef. The so-called “Roxanne Wars” are often regarded as the fountainhead from which all subsequent hip-hop feuds sprang.

Most casual observers also credit ’80s and ’90s hip-hop with inventing the preferred currency of those beefs: the diss track itself. And while certainly no musical form has embraced or commodified conflict quite so effectively, other, older genres decidedly hit it first. Twenty-five years before Tupac called Biggie and Junior M.A.F.I.A. “some mark-ass bitches,” former Beatles were trading barbs. John Lennon felt that Paul McCartney had taken shots at him in Ram — McCartney’s strange yet intrepid second solo album — and Lennon wasn’t being paranoid: the back cover of Ram features a photograph of a stag beetle mounting another. In “How Do You Sleep,” a B-side track from Imagine, Lennon returned fire:

So Sgt. Pepper took you by surprise

You better see right through that mother’s eye

Those freaks was right when they said you was dead

And one verse later:

The only thing you done was yesterday

And since you’ve gone you’re just another day.

The truth about the history of diss tracks is that they go back much further than modern music. Centuries further. In the Middle Ages, flyting was a ritualized and poetic exchange of insults between two parties. Yes, vikings invented freestyle rap battles. The verbal assaults were highly personal and often sexual or scatalogical in nature. Flyting was performed as entertainment in various royal courts and slowly got baked into contemporary literature. From Beowulf to Chaucer to Shakespeare, sick burns abound.

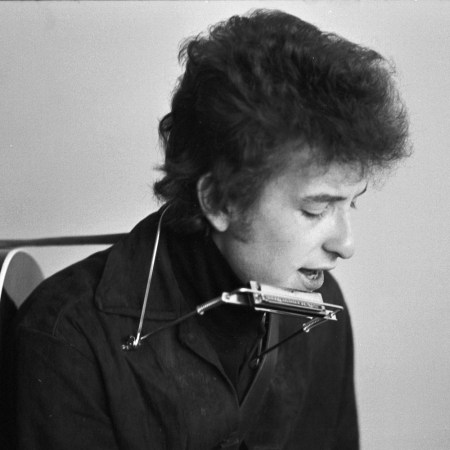

But in terms of connecting flyting to 20th-century music and the rise of the diss track, any discussion that omits one Bob Dylan is incomplete.

“One thing I know: Bob used controversy to feed his art,” wrote Suze Rotolo, Dylan’s first serious girlfriend, in her memoir. Rotolo, whose Mona Lisa smile adorns the iconic Freewheelin’ cover, inspired many of the singer’s most beautiful songs — as well as at least one of his cruelest.

Here, in chronological order, we revisit five early songs that justify Dylan’s status as an unheralded master of the diss track. They are scathing and callous, but they’re also steeped in poetic beauty. Like the flyters of yore, the Nobel Laureate proves that invective is an art.

“When the Ship Comes In”

On a 1963 road trip, a California hotel clerk refused to rent Dylan a room. Dylan was a rising star but not a nationally recognizable figure yet, and the clerk didn’t approve of his disheveled appearance. As Dylan erupted, multiple hotel employees rebuked him. Finally, Joan Baez intervened and secured a room. (The two were romantically involved, though Baez was considerably more famous at this point.) Dylan was still fuming when he entered his room and furiously started to write. “I could see him hanging them all,” Baez told Martin Scorsese in his 2005 documentary No Direction Home.

Selected lyrics:

Then they’ll raise their hands

Sayin’ we’ll meet all your demands

But we’ll shout from the bow your days are numbered

And like Pharaoh’s tribe

They’ll be drownded in the tide

And like Goliath, they’ll be conquered

Who says spite isn’t a muse? Draped in religious and mythic imagery, “When the Ship Comes In” is an epochal tale about vanquishing oppression. And it all sprouted from the creative seed of indignation. Being denied a hotel room triggered an alchemical reaction: Dylan’s fiery resentment and sublime lyricism produced a burn track of biblical proportions, but it’s also incredibly uplifting (provided you identify as one of the ship’s passengers). Dylan debuted the song at the March on Washington, a landmark moment in the civil rights movement.

“Ballad in Plain D”

Even Taylor Swift’s breakup ballads aren’t as biting as this one, which details the blowout that led to Dylan’s painful split with Suze Rotolo. What makes it so unusual is that the fight was not with Suze but her older sister, Carla, whom Dylan accused of poisoning their relationship. “Carla and Bobby each felt the other was bad for me,” Rotolo said in her memoir. “Neither of them was mistaken about that.”

Selected lyrics:

Of the two sisters, I loved the young

With sensitive instincts, she was the creative one

The constant scrapegoat [sic], she was easily undone

By the jealousy of others around her

For her parasite sister, I had no respect

Bound by her boredom, her pride to protect

Dylan’s biographer Clinton Heylin argues that his “portrayal of Carla as the ‘parasite sister’ remains a cruel and inaccurate portrait of a woman who had started out as one of his biggest fans, and changed only as she came to see the degrees of emotional blackmail he subjected her younger sister to.”

In one verse, Dylan assigns himself some abstract blame for his role in the relationship’s demise: “Myself, for what I did, I cannot be excused … for the lies that I told her.” Rotolo is a bit more direct in her memoir: “Yeah, he was a lying shit of a guy with women, an adept juggler, really.” But, remarkably, she bore him no ill will for attacking her sister in such a public way. “I understood what he was doing. It was the end of something and we both were hurt and bitter. His art was his outlet, his exorcism. It was healthy.”

An older Dylan, however, had a harder time forgiving himself. According to Heylin, Dylan singled out “Ballad in Plain D” when an interviewer asked him in 1985 if he ever regretted writing any songs. “That one I look back at and say, ‘I must have been a real schmuck to write that.’ I look back at that particular one and say … maybe I could have left that alone.”

“Ballad of a Thin Man”

Like the final two tracks on this list, the specific target of “Ballad of a Thin Man” is a mystery despite much speculation. The song addresses a man named Mr. Jones, an interloper who becomes more confused the more he tries to understand what is happening around him. Many Dylan aficionados will tell you that Mr. Jones represents the journalists who tried to pin Dylan down over the years. Dylan’s most concrete remarks on the subject don’t refute this.

“This is a song I wrote in response to people who ask questions all the time,” Dylan said at a concert in 1986. “I figure a person’s life speaks for itself, right? So every once in a while you gotta do this kinda thing — put somebody in their place.”

Selected lyrics:

Well, you walk into the room like a camel, and then you frown

You put your eyes in your pocket and your nose on the ground

There ought to be a law against you comin’ around

You should be made to wear earphones

‘Cause something is happening and you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mr. Jones?

Phonically, this is everything you want out of a diss track. The minor chords that Dylan hammers on the piano are taunting. Al Kooper’s organ is haunting. And Dylan’s vocals positively drip with disdain. The lyrics don’t always make sense, but their intent couldn’t be clearer. If you’re ever looking for insults to hurl at a foe — to sting but also leave them confused for days — Dylan offers some choice lines.

According to Kooper, when the studio musicians listened to the song after recording it, drummer Bobby Gregg turned to Dylan and said, “That is a nasty song, Bob.” It’s not hard to picture the sneer with which Dylan surely received this as a compliment.

“Like a Rolling Stone”

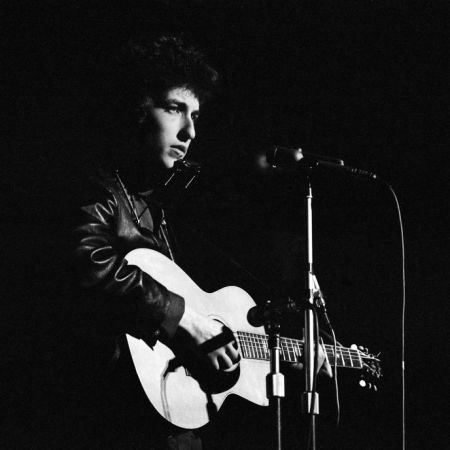

After returning from his 1965 tour of England, the one documented in D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back, Dylan was ready to quit music. “I was very drained, and the way things were going, it was a very draggy situation,” he told Playboy in a 1966 interview. “But ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ changed it all.”

Dylan’s most famous song started as a “long piece of vomit, 20 pages long.” From the detritus, he culled four verses and a chorus that would forever change contemporary music. The marathon recording sessions that shaped the song’s sound are part of its legend, but the wrathful schadenfreude of Dylan’s lyrics fuels its nuclear core. The real identity of Miss Lonely, the song’s fallen heroine, has never been established — if she’s even based on a single individual — but the gleeful enmity of her creator is very real.

Selected lyrics:

You used to laugh about

Everybody that was hanging out

Now you don’t talk so loud

Now you don’t seem so proud

About having to be scrounging your next meal

We all know people like Miss Lonely. People who lead lives without empathy, who treat the world as their open bar and cackle at the misfortune of others. We resent them. Not just because they’re self-righteous assholes, but because the universe lets them get away with it.

But every now and then they fall. Unless they’re a public figure — someone we can openly root against — we tend to celebrate their comeuppance quietly, with a pursed smile or a sarcastic whisper to a confidante. Couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy! But we’ll generally refrain from open joy. Dylan, though, smashes this restraint like a piñata.

“It’s a black eye of a pop song,” Bono wrote in an essay for Rolling Stone magazine. “The verbal pugilism cracks open songwriting for a generation and leaves the listener on the canvas.” Bono proceeds to crown Dylan as “the king of spitting fire,” which is just a synonym for diss-track savant.

“Positively 4th Street”

In Greenwich Village in the early ’60s, starving artists and aspiring folk singers were as prevalent as fish in a koi pond. When Dylan turned into a great white shark, many of his peers struggled to accept his success. “We all started out with the same equipment — guitars and voices — and one of us was suddenly a comet,” folk singer Tom Paxton told Heylin, Dylan’s biographer. “It’s unsettling, and nobody’s going to handle it perfectly.”

Jealous contemporaries would talk behind Dylan’s back, mock his voice, thrash his songs or simply ignore his newfound fame. For his part, Dylan was not above pettiness. One day when he was riding in a limo with a bunch of other musicians, he played his new single “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” and asked what people thought of it.

Almost everyone heaped praise, but the singer Phil Ochs said he didn’t like it. A perturbed Dylan asked why, and Ochs replied, “Well, it’s not as good as your old stuff, and speaking commercially, I don’t think it’ll sell.” Dylan proceeded to throw Ochs out of the car (though Ochs’s prediction proved accurate).

“Positively 4th Street” is Dylan’s way of throwing all the Greenwich Village haters out of his car and under the wheels.

Selected lyrics:

I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes

And just for that one moment I could be you

Yes, I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes

You’d know what a drag it is to see you

What an acerbic appropriation of Atticus Finch’s famous empathy lesson!

“Positively Fourth Street,” Heylin observed in his biography, “made ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ sound like ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand.’”

When I was a high school English teacher, I used this song to teach juxtaposition. By itself, the happy-go-lucky melody could be the soundtrack to a golden retriever’s dream. But the lyrics are vicious, and the contrast amplifies the acidity.

*****

Critics will argue that Dylan’s cryptic approach in many of these diss tracks is cowardly. He seldom identifies his burn victims, a trait that makes hip-hop beef so spicy. This interpretation, however, lacks context.

Dylan’s meanest songs were written at a time when it was unheard of for singers to weaponize their art, let alone name their targets. (One notable exception is Lee “Scratch” Perry, a dub pioneer who released a number of songs in the late ’60s and ’70s lampooning other musicians; Perry was also the innovative producer behind several Bob Marley albums.) But the fact that Dylan imbued his lyrics with such palpable bitterness was groundbreaking.

His musical forebears, idealistic folk singers, kept their artistic motives aimed aspirationally skyward. Dylan had no qualms about playing in the mud. Highway 61, the vinegar-infused album that houses two of the songs on this list, was the paved road that mainstreamed diss tracks for future artists. It proved that in the world of high art, low blows and poetic beauty are not mutually exclusive.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.