When I pause the screener of director Suzanne Joe Kai’s documentary Like a Rolling Stone: The Life & Times of Ben Fong-Torres, I’m disoriented for a few seconds. You mean I’m not in San Francisco in 1967?

Kai’s immersive documentary, which made its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival this past weekend, follows the life of Fong-Torres, the pioneering editor and journalist who joined the iconic publication within five months of its founding. It was the height of the 1960s counterculture era, and if you were a young person who wanted to know what was going on in the world, you flocked to the magazine.

Rolling Stone was, like the people it chronicled, a voice of its generation: in the swirling sociocultural revolution of the 1960s, the magazine became a juggernaut of truth thanks to unprecedented access to and coverage of the worlds it covered. Legends from Stevie Wonder to John Lennon read the magazine, and landing a review in its pages could make or break a career. During his tenure as a writer and senior editor, Fong-Torres was able to shape the culture at the magazine, making him an integral part of modern American history.

Even so, Kai realized, Fong-Torres’s was a story that hadn’t been told. He had been a talking head in so many rock documentaries, but deserved one of his own. Her process began 10 to 12 years ago over drinks with the journalist, who she’s known for many years. “He said, ‘Well, why don’t you just do one?’ and I did,” she tells InsideHook with a laugh. Though it started as what Kai calls a “fun rock and roll documentary,” things quickly evolved from there.

Kai is a regarded journalist herself, and, like Fong-Torres, one of the first Asian-American journalists in mainstream print and broadcast media. “In those days, there were almost no Asian Americans in media in front of or behind the camera. Ben was among the first,” she says. As her process went on, the story took on new layers. “The more I got deeply into the research, I thought, how is this even possible that this is not out there in the mainstream and only the insiders know?” she says. “[It was] still a ‘fun and games rock and roll documentary,’ but now with a mission, a purpose to help America understand itself.”

That the film comes at a time when Asian Americans have been experiencing an appalling uptick in hate crimes is powerful to Kai. “It’s really hard for me to fathom the timing of the premiere of our film given that it has taken so many years to make and then all of a sudden it premieres at the moment where Asian Americans are being hard hit,” she says. “We’re in a crisis moment. Our people are being hurt in the streets … violence, racism, the things that are hard to even imagine happening in 2021. So [with] this film I want to entertain audiences, but in entertaining I also want to introduce an Asian American who has done great things and is really beloved by so many walks of life, all backgrounds.”

Throughout the course of the film, we follow not just the development of Fong-Torres’s career, but the life events that brought him there. Because of the racist Chinese Exclusion Act instituted in 1882 and not removed until 1943, Chinese people were banned from immigrating to the U.S. Fong-Torres’s father adopted a Filipino birth certificate to circumvent the process and make a life first for himself and then for what would become his family.

Ben was born in Alameda, California in 1945, but later moved to Texas with his dad. There, as the only Asian American in a school of all white students, Ben encountered racism from some school faculty, but wanted to fit in with his peers. Music was his way in. “I tried to be cool. The passport to cool-dom in 1957 was rock and roll,” he says in the documentary, recalling the Elvis Presley songs he used to lip-sync in the mirror. “Rock and roll was an equalizer.”

When the family relocated back to Oakland, California, Ben worked at the family restaurant while attending high school. He didn’t think his life was that interesting, and sought to listen to others’ stories instead. “When I was able to go to a party in high school, for example, I would often wind up asking people questions and never talking about myself,” he says in the film. “I think I felt like, what’s there to say about bussing dishes? And so I began to take notes on other people’s affairs, events and news, and that probably led to the choice to be a writer about other people’s stories.”

Knowing these stories, it’s understandable that Fong-Torres found a home in journalism, and in music journalism in particular. At the beginning, despite his own achievements as a college newspaper editor and reporter, he didn’t really know what his job prospects would be. He only knew there was nobody who looked like him in the field. Ultimately, it didn’t matter. Fong-Torres did his first feature for Rolling Stone as a freelancer in 1967 on the singer Dino Valenti. “We were dealing with whatever kind of flakes off the street wanted to write about rock and roll, and Ben was a serious journalist and he was a skilled writer, too,” said former magazine proofreader Charles Perry in the film. Ben was hired full-time shortly after.

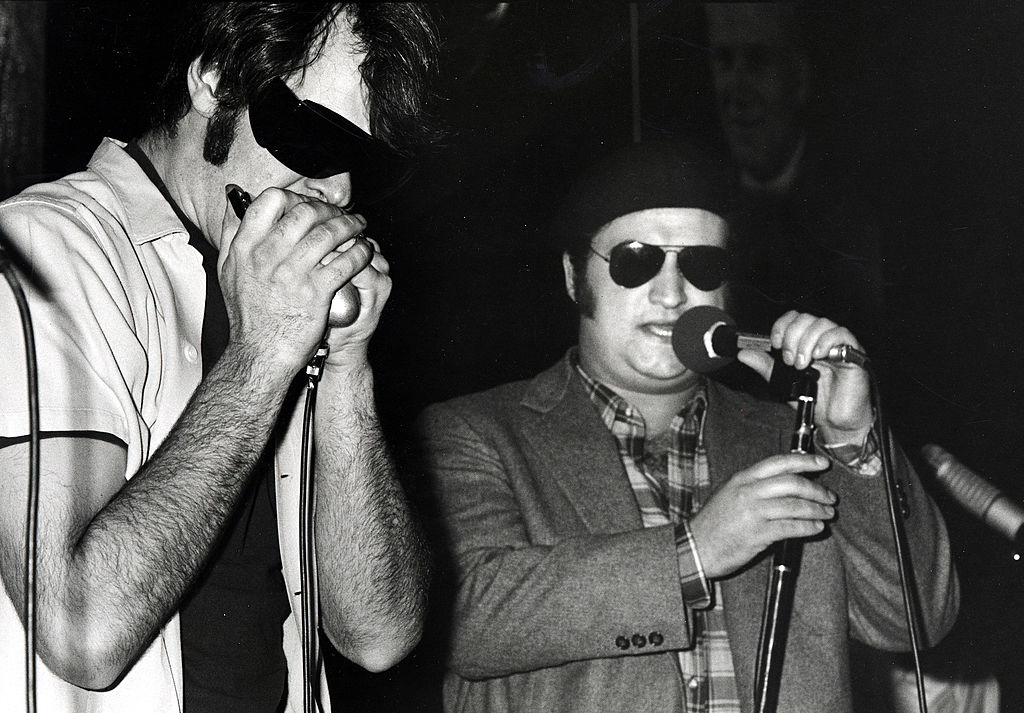

His influence soon became undeniable, though it’s something he wouldn’t notice himself. Many bands refused to speak to anyone at the magazine but Fong-Torres and he had unrestricted access to the behind-the-scenes and backstage lives of musicians. Soon he was a star in his own right. “You wouldn’t get that today, ever. You’ve got all these corporate handlers and they’re staring everybody down and they have guidelines, you can’t ask these questions,” Kai says. “Ben was one of one … There were other journalists from other magazines, but probably not at the level of what Rolling Stone was able to achieve so rapidly in the early years.”

The interviews in his archives are the stuff of legend: Ray Charles, Jim Morrison, Tina Turner, Paul McCartney, Linda Ronstadt. The level of detail the artists share is stuff for the history books, all prodded out of them by an incredibly skilled journalist who always asked them to “tell me more.” In 1974, Fong-Torre won a Deems Taylor Award for Magazine Writing (principally for the Charles interview), and his career continued to thrive even after he left Rolling Stone in 1980, choosing to stay in San Francisco after the magazine’s departure to New York. In the four decades since, he’s enjoyed a prolific career in all aspects of media, broadcasting and publishing.

For people who love music and magazines (or both), Fong-Torres is a name of near Rushmore-ian proportions. If you loved Cameron Crowe’s 2000 film Almost Famous, you have Fong-Torres to thank: he actually gave Crowe his first assignment at the magazine when the writer was just a teenager. But Kai’s film allows that audience to expand beyond those “in the know” and pushes Fong-Torres into his proper place in the annals of American history. “My only hope is that we establish him and truly appreciate and recognize what he’s really done. That is my mission. And that carries on to helping current and future generations to be inspired by what he has done,” Kai says.

Throughout it all — and even at the Tribeca screening — Fong-Torres has remained humble. As the film played on a giant screen, he stood toward the back of the crowd in a grey suit jacket and black slacks, bopping his head along to the Jimi Hendrix and Ray Charles tunes that soundtrack the film. He paced, he took pictures on his phone.

“What my associates and some of the musicians with whom I dealt, I have to say, I really did not know — as [former RS staffer] Cynthia Bowman said — ‘He probably doesn’t know about his power,’” he admitted in a Q&A at the end of the film. “I did not, and it was probably better that way. Just do your job, and [don’t] worry about anything else.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.