This year marks the 60th anniversary of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, a beguiling, shocking, sexy, cruel film that takes aim at our culture’s celebrity worship. It is also one of cinema’s enduring masterpieces, frequently featured in film critics’ “Top Ten” lists — and one of the late Roger Ebert’s all-time favorites.

It might be called “the sweet life,” but this is a dark film, as likely to leave you hungover with emptiness as happily entertained. The suits, parties, starlets, all conceal Fellini’s real idea of fame (and the media) as hysteria-inducing — simmering, until the pressure boils over into disillusionment, or worse: death. We follow Marcello Mastroianni’s bored gossip columnist as he prowls the streets of Rome like a sad panther, seeking out tittle-tattle from the city’s glitterati. Seven loosely-knit episodes unfold between day and night, as Marcello loses himself in social decay and scandal.

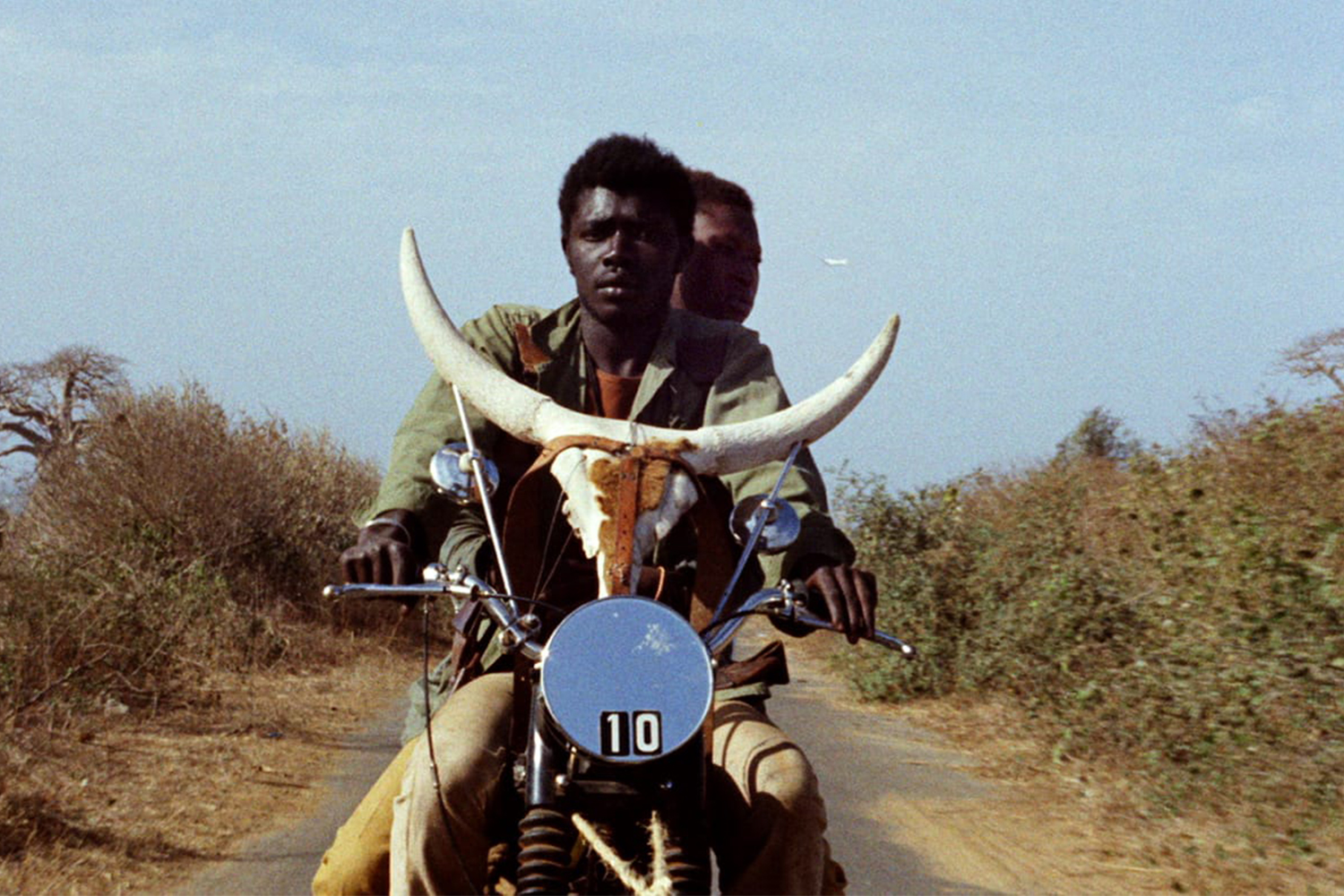

La Dolce Vita is full of iconic moments. There is that scene of Anita Ekberg frolicking in the Trevi Fountain, or Marcello cruising his slick Triumph TR3 down the Via Veneto. But the film is immortalized for another more unintended reason: Paparazzo (played by Walter Santesso) the young, otherwise minor newspaper photographer, whose name came to define a new generation of persistent and sometimes predatory photojournalists. “When we talk about paparazzi, there is before and after La Dolce Vita,” Rick Mendoza (@sellebrityrick), a veteran Hollywood paparazzo (who has photographed everyone from Barack Obama to Paul McCartney), tells InsideHook. Not only did it coin the term paparazzi, but it may also have popularized our general dislike for them too: “The film created a stigma that we deal with to this day, as pushy, aggressive opportunists.” True enough, young Paparazzo and his fellow photographers swarm to their victims like flies in a dump. Bystanders are appalled. In one sad scene (spoilers), they surround and harass the wife of a man who murdered his own children — clicking away in her face, forcing her to break down in tears. It remains hard to watch now, let alone in 1960.

The film itself was actually inspired by a real-life scandal known as the “Montesi Affair.” After a drug-and-alcohol-fueled party held by Rome’s aristocracy in 1953, the body of 21-year-old Wilma Montesi was found mysteriously washed up on a beach in Ostia (the same where Marcello encounters a sea creature in the film’s climax). Witnesses suggest her body had been secretly dumped. Once Montesi’s death was publicized, all of Italy wanted in on the scandal, with outrageous (and not entirely true) stories of sexual slavery, prostitution, and orgies conjuring a Caligulan fresco of Roman decadence and rot.

One such tale told of an unknown actress named Ursula Andress, who had a bottle thrown to her head by a Count. “The Montesi Affair changed everything,” says Rick. “Before, the paparazzi was recognized as a necessary fixture in Roman society,” but once the Pandora’s Box was unleashed on the Italian public, “it was a battle for the best shot.” For the first time, people saw what went down at those high-society parties (and it wasn’t tail-coats and Bach). As tabloids fought for the most shocking scoops, photographers switched-up their practice to feed a gossip-hungry public. Paparazzo was that newer breed of photojournalist: egging on fights and leaping into moving cars (“my favorite scene… No matter what, get that shot,” laughs Rick), simply doing whatever it takes — even at the risk of his or his friends’ safety.

A third of the way through, Paparazzo follows Marcello to an alleged sighting of the Virgin Mary. While observing a priest conduct a sermon, he performs the cross with his right hand and then moves that very hand to the shutter, and ‘click’ — the camera goes off. It’s a beautiful moment because it proves you can serve the Scandalous and the Divine at the same time.

Italy in the 1960s was, of course, a devout place. After the Vatican condemned the film on release (“Disgusting” — for its liberal sexuality and Godlessness), senators introduced it to parliamentary debate. La Dolce Vita was very nearly banned.

Consequently, Fellini was at the center of his own scandal. He received death threats for his “atheism,” was regularly booed at cinemas, and in one nasty incident got spat on in public. (The film was only released in Spain after Franco’s death.) But rather than discourage people, they flocked to the cinemas. La Dolce Vita became the highest-grossing foreign-language film at the US box-office that year (making more than any other foreign film before it), and remains number 13 for most cinema admissions of any language in Italy, just below Titanic. The buzz proved Fellini’s point: people didn’t go en-masse because they heard the plot was good, but because they knew they were going to see something outrageous. If the Vatican calls your movie, “Godless” — it’s still a great PR bump.

Sixty years on, people have turned the cameras on themselves. The scandal hasn’t changed, Rick notes, just the people: “Tabloids still want stories that acquire so much attention that the news goes viral or even global.” La Dolce Vita may have exposed the snobbish glitterati, gossip hounds, baroque royals, and fading starlets of its own time, but today you are more likely to read about delinquent vloggers or clown politicians. And they’re not shy to scandal, either. In most cases — the Logan Paul and KSI boxing match, the President’s Twitter feed — being bad in the open can be wildly profitable.

Rick believes social media has hurt the paparazzi. “All sensationalism is now made personal, as celebrities share intimate moments with their fans,” he says. “You can now see scandal on a daily basis and in real-time.” Today’s Influencers are stars and paparazzi rolled into one, and instead of the café-lined Via Veneto or New York’s Fifth Avenue, those stories are now sought on Instagram grids and YouTube. Yet while the Montesi Affair may be mild by current standards; the event, and the film it later inspired, continue to influence our view of celebrity and the press.

Right at the movie’s end, there is a party scene that threatens to get out of control. It is a direct nod to the Montesi Affair; women are beaten, a wealthy actress strips. A desperate actor asks Marcello what he would write for a few thousand Lira. “For that,” he replies, “I will make you Marlon Brando.”

Today he wouldn’t even have to pay; all he has to do is download Instagram.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.