“A great man is gone,” wrote the poet e.e. cummings, “Tall as the truth…”

And a great man, Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker, is gone.

Walker’s doctorate, he would tell you, was earned, not honorary. And all his life’s honors were earned — a thick volume full — by hard work, noble work and bravery.

I had the unexpected pleasure in the middle of my life of getting to know Dr. Walker as a friend, partner and mentor — a most unexpected pairing because I am a white “Wall Street guy” from Michigan who would never have expected to cross lives with a civil rights icon and Harlem minister.

But I had left my Wall Street job in 1999 to start a charter school — the first and longest lasting in the State of New York — and Dr. Walker was searching for a path to bring better education to the kids in Harlem and elsewhere. We teamed up together to found that first school on 115th Street between Lenox and St. Nicholas, in the “Center For Community Enrichment” building at the back of his Canaan Church; a building which had been built through weekly tithes from his parishioners.

The school was originally called (at Dr. Walker’s suggestion) the Sisulu charter school in honor of Walker’s friend and Nelson Mandela’s ally, Walter Sisulu. Later, the school was proudly renamed the Sisulu-Walker school in honor of Dr. and Mrs. Walker as well. The story of the school and of our work together to start it was the subject of the book A Light Shines in Harlem by Mary Bounds.

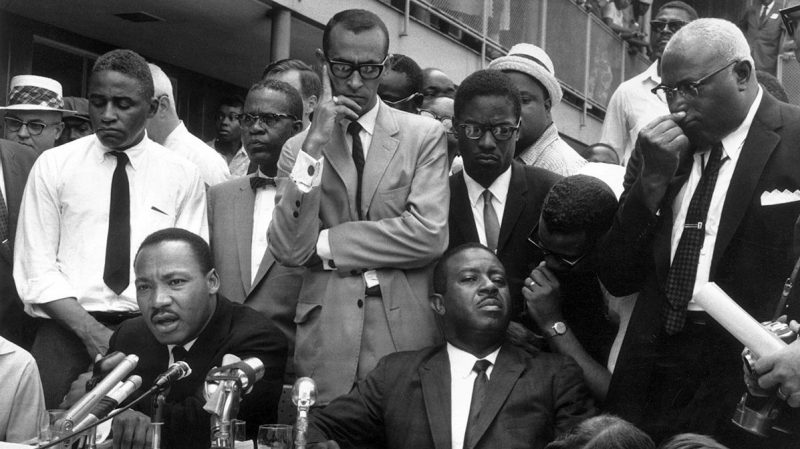

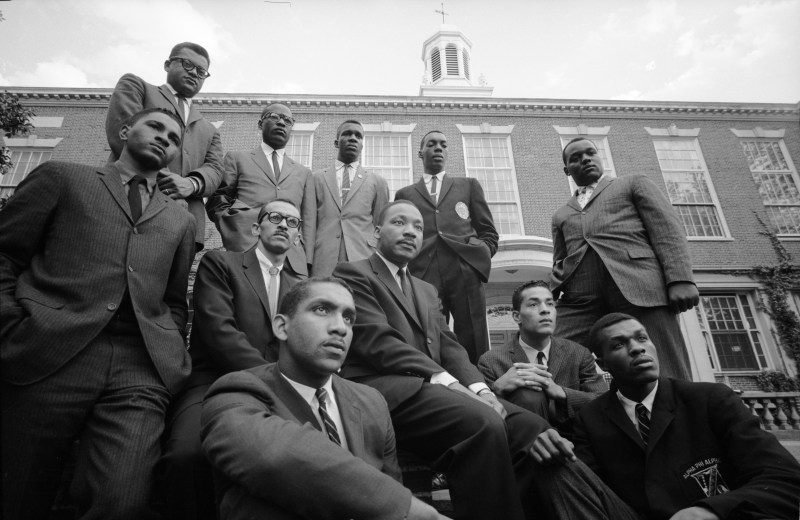

Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King (right) installs the Rev. Wyatt T. Walker as pastor of the New Canaan Baptist Church in March 23, 1968.I had heard about Dr. Walker’s reputation before I ever met him. In early 1999, when I began to work on charters, I had been traveling among New York’s most educationally under-served communities, searching for allies and a school location, accompanied by a young theological student named Marshall Mitchell. Marshall’s father was the Philadelphia minister Frank Mitchell, who had been a colleague of Dr. Walker’s, and Marshall urged me to meet Walker.

The decision was not a simple one. Dr. Walker was an imposing figure, who was known among his fellow ministers as a man who did not suffer fools gladly. His precise diction and manner could hit like a lightning bolt when he so chose.

Furthermore, it was February 1999, just a day or two after the innocent, unarmed immigrant Amadou Diallo had been killed by 41 police bullets. Rudy Giuliani was mayor and racial tensions in New York were running high. Walker was chairman of Al Sharpton’s National Action Network and at the center of the storm, and Walker and Marshall Mitchell were among those being arrested in symbolic protest. Until my school efforts, I had spent almost no time “north of 110th Street” and it was an inauspicious time to start a friendship.

Still, my ambition overcame any barriers, and I traveled uptown to meet Dr. Walker. I first saw him at the Imam’s restaurant in the base of the mosque on 116th and Lenox, just a few doors east from Dr. Walker’s own church, Canaan.

Dr. Walker has often been compared in looks to Sean Connery, and its an apt comparison. When I first saw him, at age 70 or so, he was tall, strong, elegant, with grey hair and a well-trimmed beard.

He took me over to Canaan. We passed through the glass front doors of what had once been a grand movie theater, and into his private interior office, warm and full of books and mementos. I remember the magazine covers high on the wall above the door, including Jet magazine from around 1963, “the Man Behind Martin Luther King”; professional–quality photos that he himself had taken of King and of the dozens of countries he had visited on his travels; mementos of his boat, The Lady Ann, named in honor of his exceptional wife of 67 years, Theresa Ann Walker. A yachting cap? And I felt better to know that he was a man who loved happiness in life as well as struggle – still one of the characteristics I most admire about him.

He explained his desire to have a school. The local public schools in Harlem had been failing for decades; the children were not being educated. Starting a successful school was a great financial, regulatory and technical challenge, but partnering with me under the charter law could give him the means he needed.

The charter law had passed under Gov. George Pataki’s leadership in New York just months before. Walker and his fellow ministers, including Al Sharpton and Ruben Diaz had been vocal advocates for the change, and united the charter school movement with the civil rights movement from the very beginning. “The schools had to get better, “Walker later said, “I saw that as an extension to my work in the South.” And he also said, “I’m a disciple of Martin Luther King. I think I know as much as anybody of what he would support.” And Walker believed King would clearly support charter schools.

Once we agreed to join together, Walker and I spent several months meeting regularly to agree on the school design and logistics, usually accompanied by his chief of operations at Canaan, “J.P.” (the exceptionally capable Judith Price, who passed away several years ago), and by Marshall Mitchell.

That summer, Marshall and I spent more than one night in the great room in the basement of CCE, “Embassy Hall,” persuading local parents to trust their kids’ future to this new and unproven school and education idea. As much as anything, it was the community’s knowledge that this was “Dr. Walker’s school” that bought us enough credibility to be listened to at all.

Eventually, the school would outperform the other public schools in its central Harlem neighborhood. We rang the school bell as the first charter kindergartner in New York State entered our front door on September 8, 1999. And by June 22, 2005, as that same class graduated from Sisulu-Walker as fifth graders, 90% tested at grade level or above on the state exam for reading (almost twice as many as in the nearby traditional schools) and 77% were at or above grade level in math, vs. 30% for the traditional Harlem schools.

Dr. Walker was our spiritual mentor each step of the way, and became a personal friend and mentor as well. When the school’s starting budget was tight, he found rooms full of brand new school furniture, available free from another church school closing up north. He became an advocate and speaker to other charter schools and an ally in spreading the charter school mission.

On my book shelf, I have a photo of us together, and I remember when he came by my office to take it, looking fit and strong and telling me how well his new exercise campaign was paying off. Then, it feels like just weeks later, on January 4, 2002, I received word that he had been laid low by a terrible stroke – much as I received word he had died Jan. 23. Because of the stroke, one of the great orators of our age found it impossible to speak clearly, and the left side of his face sagged. His vitality was sapped in an instant.

Eventually, he retired to his once home state of Virginia to recuperate, with Ann to help him. It was the State where he had walked defiantly through the “whites only” door of the Petersburg public library in 1960, and asked to check out a book on Robert E. Lee!

His body was weak after the stroke, but his mind stayed clear and strong. He wrote a book about his health trials My Stroke of Grace, one of the more than twenty books he wrote, to inspire others to better health and to urge them to maintain hopefulness in the face of illness.

He continued to cheer on the charter school movement and to remain my friend from a distance. When Mayor Michael Bloomberg came to Sisulu-Walker School and to Canaan’s sanctuary to give a speech in support of the charter movement, Dr. Walker wrote me in a never before published letter (extracts of the letter only):

Dear Steve::

YOU HAVE WON THE BATTLE! The pronouncements by Mike Bloomberg have verified the success of the Charter School movement in New York. …It is akin to us getting rid of segregation in the body politic of the nation….Now the real struggle begins to fashion our strategy for the future. It will be a daunting task. We must plan an attack similar to Project C Birmingham. …I wanted to get this word to you ASAP!…Grace and Peace, Wyatt Tee Walker

Travel became very difficult for him, and he returned to New York very rarely. On one trip, I was with a group that honored him at Harlem’s Alhambra ballroom, and was able to see him quietly nod his acceptance of his own name being put into the name of the Sisulu-Walker school.

I was able to visit him in Virginia and to deliver his and her iPads to Dr. and Mrs. Walker; a way to keep his still vibrant mind fully connected to any book, music piece or news report. At this time, Dr. and Mrs. Walker each sat for a video interview with me which we have run on RealClearLife.

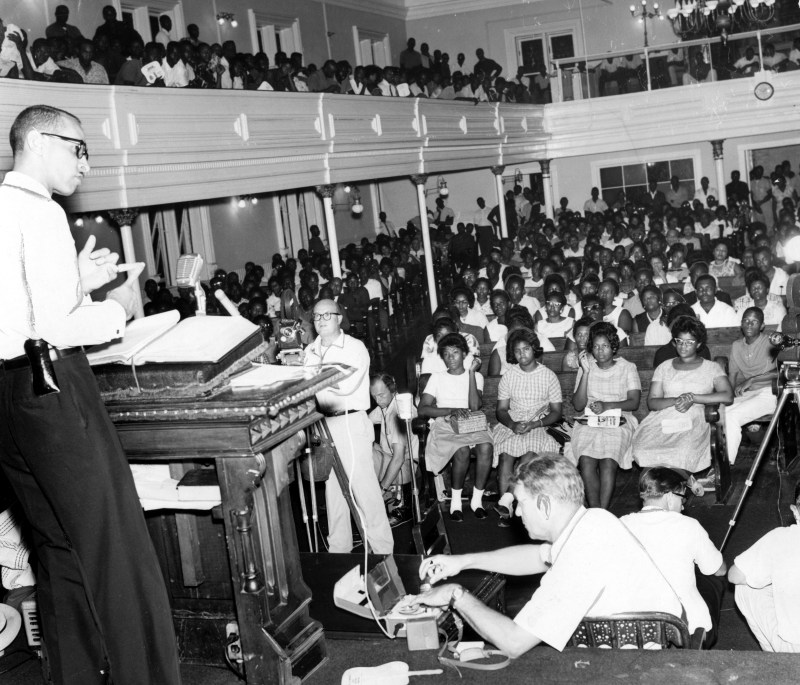

In his 2016 interview, Walker expressed his great love for Martin Luther King and his belief that the movement would have been far more advanced if King had lived. Walker remained a strong advocate for charter schools until the end, and for other causes such as economic reparations for African Americans. He considered the Birmingham march as the key event in the civil rights battle and recalled the critical days of civil rights as one where there could be no thought of losing. He also retained his humor telling me his favorite joke of the era.

To paraphrase it, Dr. King and Rev. Abernathy came to Birmingham and were looking for directions to a small church. A passerby was flabbergasted to see King in the flesh, but didn’t know where the church was. As King’s car was driving away, they saw the same man running frantically to catch the car. “Dr. King!, Dr. King!” the local man said, “I asked my brother about the church. And he don’t know either!”

Mrs. Walker – a great figure in her own right – had her own stories to tell, including her memories of being in the Gaston Motel in Birmingham with the two youngest of her four children on the night it was bombed. Then, as she drove away from Birmingham with all four kids, she was forced by police to pull over, and thrown into jail for not pulling over fast enough. She was in jail on Mother’s Day. With her four children! She used her one phone call unsuccessfully, and then her oldest daughter’s call for a second attempt, that got through to Daddy King and to a local undertaker who owned enough debt-free property to post bail.

* * *

There are just a few major movements in our nation’s history: the Revolution, the Civil War, The World Wars, the civil rights movement. There are just a few sets of “Founding Fathers” that lead the nation forward at key moments, and Wyatt Tee Walker ranked high among them.

As Walker dies, a great man is gone.

A titanic figure of the civil rights era, and of human rights, from the 1950s until yesterday. Alexander Hamilton to Martin Luther King’s George Washington.

The man who was King’s field general in Project C, Birmingham, against Sheriff Bull Connor, his attack dogs and his fire hoses.

The man who compiled “The Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

The first executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

One of America’s great ministers.

A local church leader who stood up to gangster Frank Lucas and the Harlem drug dealers. Who built senior housing. Who wanted real economic opportunity for all.

But beyond his career honors, I feel touched and mentored by Dr. Walker in other deeper ways.

He fought and was human, not a plaster saint. He said frankly that he would have used violence in the civil rights struggle when it began, and was persuaded by King not to; a decision he believes was right. When his wife was hit by a policeman’s gun butt during the struggle, it was luck that kept a gun out of Walker’s own hand to fight back.

He was deeply spiritual and could be an implacable foe, but he loved life. He loved jokes, music, the good things in life. When we had become friends as the charter movement proceeded, he took me as his guest to occasional parties: him in a highly styled, African dashiki robe, me the one white guy in the room. Canaan Church had among the finest choirs in the nation under Walker’s leadership, and he mentored music groups such as “The Four Sopranos”(Harlem’s local and angelic complement to the famous “Four Tenors.”) His son Jay continues this love of music into today.

Dr. Walker also showed me in small everyday ways what true spirituality means – saying grace as I was about to dig in. Or reflecting on the death of a loved one with a quiet reminder that in his religion, the afterlife is a thing to be believed in.

He was a moral force. When other civil rights leaders needed to atone, who could call them to task but Dr. Walker?

He knew and was true to King’s fundamental vision. In an essay he and I wrote together in 2015, he reiterated his belief in “color blindness” as King’s formula for social justice; he explicitly rejected the Critical Race Theory alternative, with its misplaced emphasis on groups instead of individuals. “Today, too many ‘remedies’ — such as Critical Race Theory, the increasingly fashionable post-Marxist/postmodernist approach that analyzes society as institutional group power structures rather than on a spiritual one-to-one human level — are taking us in the wrong direction: separating even elementary school children into explicit racial groups, and emphasizing differences instead of similarities.” He was a leader in issues of race, but he saw deeper than race.

So, as the poet said, we all should say:

“a great

man

is

gone. Tall as the truth was who; and

wore his

…Life

like a …

sky.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.