2020 was a pretty big year on the internet for Orson Welles, the legendary auteur behind Citizen Kane who has been dead since 1985. In the summer, as protests against police brutality hit a fever pitch, an old radio clip from 1946 went viral where Welles passionately denounced the police beating of black man Isaac Woodard. In November, Netflix released David Fincher’s latest film Mank, an examination of who actually wrote Citizen Kane. Then in December, the New Yorker’s Richard Brody detailed the exciting discovery of Welles’s long-lost and what he called groundbreaking 1956 TV pilot, Fountain of Youth, starring Lucille Ball.

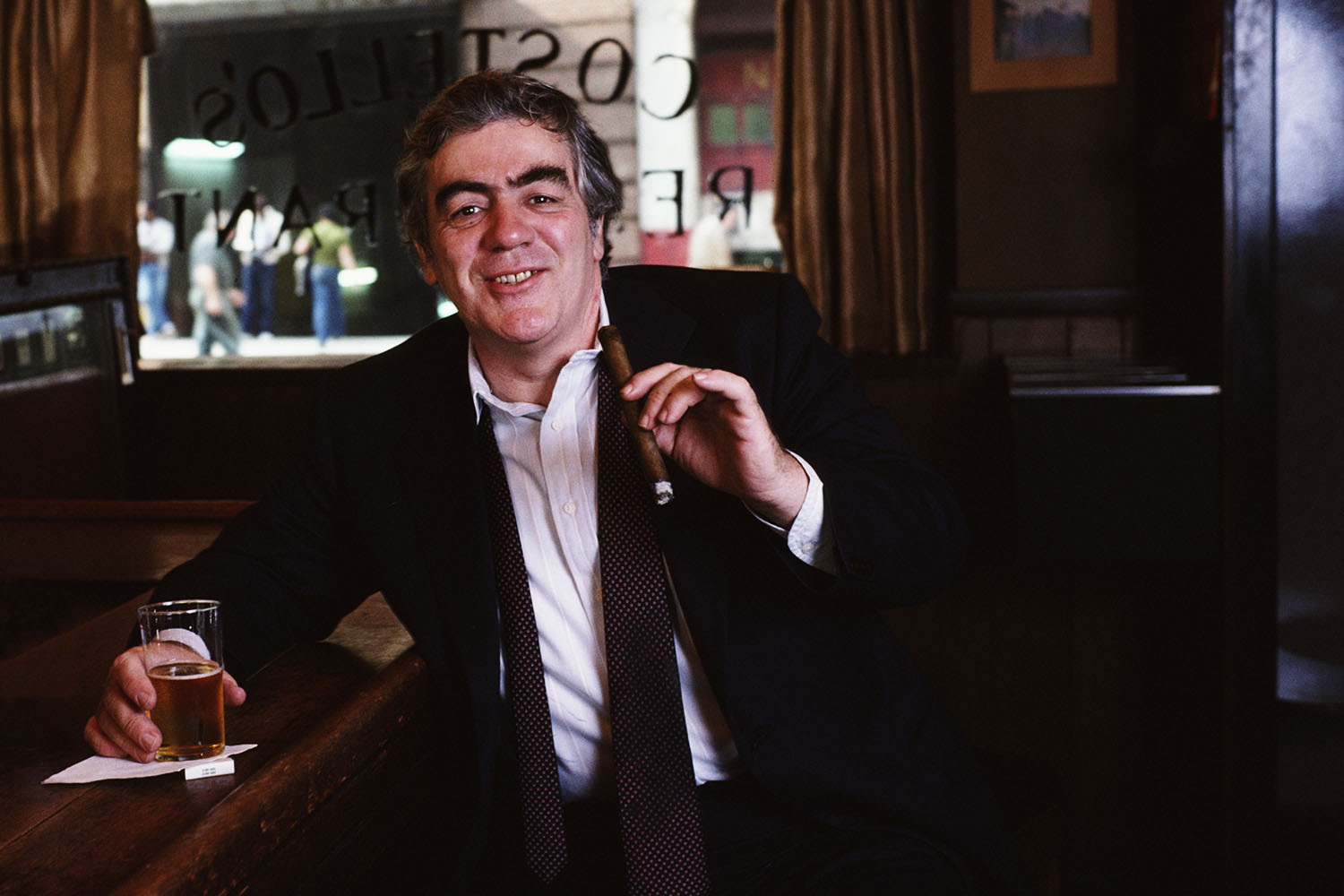

But the biggest news for Welles in 2020 was surely the 40th anniversary of the drunken outtakes from a Paul Masson champagne commercial. Something LitHub’s Dan Sheehan called, only half-jokingly, “unquestionably, the most significant cultural milestone of 2020.” At the least, it provides undeniable proof that Welles remains truly the greatest booze pitchman of all time.

Welles had always struggled to get his projects financed, but by the late 1970s he was doing particularly poorly. His most recent directorial effort — which, little did he know, would be the final directorial credit of his career — was for Filming Othello, a little-seen documentary that only aired on West German TV in 1978. He hadn’t had a theatrical feature since 1968’s The Immortal Story and was now more famous as a guest on talk shows like The Tonight Show, The Dick Cavett Show and the Dean Martin roasts.

But he was OK with that.

“Unlike John Huston, who didn’t balk at directing mediocre movies for hire in order to remain bankable, Welles was heroically unwilling to compromise as a director,” writes Joseph McBride in his 2006 book Whatever Happened to Orson Welles? “But he was willing to do almost anything as an actor/personality.”

Especially if it would make him money he could toss back into the financing of his perpetually stalled films. In fact, Welles had done commercials even back when he still a viable talent, announcing radio spots for Pan American Airlines and Lady Esther cosmetics in the 1930s and early 1940s. And that would eventually lead to him becoming a TV pitchman, starting as early as 1969 with voiceover work for Eastern Airlines.

By 1970 Welles had started appearing in British commercials for chilled peas for the Swedish frozen food brand Findus (spots that would eventually become infamous themselves). But it’s his work with alcohol brands that endures as part of his towering legacy to this day.

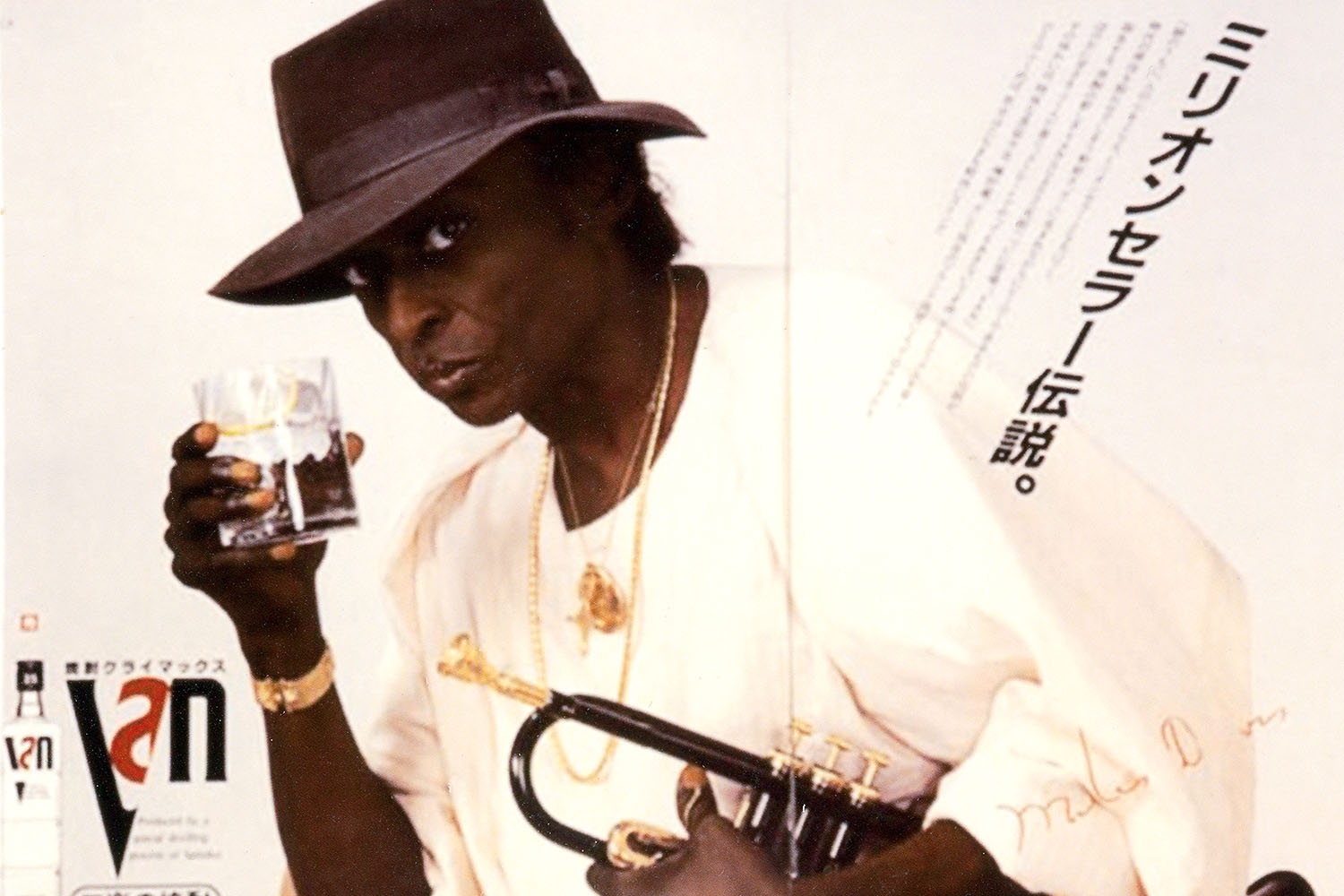

As early as 1945 he had done a radio spot for Cresta Blanca Wines. By 1972 he was doing print work with Jim Beam bourbon. By 1975 he was hawking Carlsberg Lager. That same year, he pitched Domecq Sherry, Sandeman port (in which he portrayed their “Sandeman Don” character) and Nikka Japanese Whiskey, which were a huge hit overseas.

“Welles was riding a crest of popularity in Japan as the Nikka ads started airing in 1975,” claims Robert Kroll, an English professor at St. Clair County Community College who is currently writing a book about Orson Welles’s life in commercials. The Nikka campaign was timed with a Japanese re-release of Welles’s The Third Man and even featured the movie’s score in some of the commercials. By the 1970s, Welles was earning around $15,000 a day (around $75,000 in today’s numbers) for his TV spots, according to Josh Karp’s Orson Welles’s Last Movie.

“It’s the most innocent form of whoring I know,” Welles often claimed — and, like many things, he was good at it.

Welles’s immense fame, even more immense physical presence (6’2” and over 350 pounds) and melodious baritone register added a certain gravitas to everything he touched, whether a Walt Disney World commercial or a trailer for Revenge of the Nerds. In fact, TV critic Tom Shales claimed Welles’s voice was so good, and so many people wanted to use it for commercial enterprise, that it “was virtually considered a national resource.”

One of those companies was Paul Masson, a California winery since 1892, that by 1978 was seen by drinkers as making a particularly low-end sparkling wine. According to McBride, the company big-wigs thought Welles would “provide an aura of up-market savoir faire” as they began focusing on other wines in their portfolio. (The winery’s account exec, John Bernbach, also liked that Welles “obviously [had] the image of a person who likes food.”) Welles was likewise eager for the work, as he was still trying to finish another would-be masterpiece, The Other Side of the Wind, which was languishing in a European vault.

Though Welles anonymously wrote and directed many of his own commercials (working alongside his longtime cameraman Gary Graver), the Paul Masson spots were directed by Jim Hallowes and penned by John Annarino, who built the commercials around a slogan of “Paul Masson: We sell no wine before its time.”

Playing off that theme, each ad would compare the wine to a higher art form that also took several years to create. The initial spot finds Welles in a thick black suit, pouring Emerald Dry white wine as he listens to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony on a record player. It was such a hit with viewers that Welles was signed to a permanent contract worth $500,000 a year plus residuals for both television and print ads.

The second spot would find a costumed Welles in a theater dressing room discussing the production of a fine play. Additional ads would compare the wine to other such lofty works as Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind. Welles didn’t always agree with the scripts, but he typically went along with them eventually. However, when the execs asked him to compare Paul Masson to million-dollar Stradivarius violins for a spot (which was never filmed), Welles took umbrage.

“Come on, gentlemen, now really!” said Welles, as reported in Barbara Leaming’s Orson Welles: A Biography. “You have a nice, pleasant little cheap wine here. You haven’t got the presumption to compare it to a Stradivarius violin. It’s odious.”

Those who worked with Welles on these spots, like Annarino, have admitted that working with the film titan was “no picnic.” He would insult his directors, criticize the screenplays and treat the extras like garbage (“I wouldn’t have these people at a party at my house,” Welles claimed during one Paul Masson spot meant to be at a soiree he was hosting). Yet, despite Welles’s often surly behavior on set, Paul Masson was said to be “a very happy client.” And, why not? Sales had risen 30% during the Welles advertising campaign.

Welles wouldn’t have returned the admiration to his employer, however.

“I’ve worked for advertising agencies all my life,” Welles claimed in Peter Biskind’s My Lunches With Orson. “In the old days in radio, you worked for them, because they were the boss, not the network. And I have never seen more seedier, about-to-be-fired sad sacks than were responsible for those Paul Masson ads. The agency hated me, because I kept trying to improve the copy.”

If he was notoriously demanding on set, it was often in trying to improve the quality of the commercial — he would rewrite lines, advise the cinematographer on how to light his face and from what angles to shoot, and even show up to set with his makeup already done.

Another reason he may have been so rascally on set was due to him having in his contract that he receive a multi-course, boozy lunch every single shoot day. During those meals Welles usually finished off all the cabernet in the room. And this is what surely led to Welles’s most famous Paul Masson spot, which today is surely more known (and seen) by a younger generation than Citizen Kane or The Magnificent Ambersons.

Dressed in a black suit, slightly rocking in his chair, the off-screen director yells “Action!” but Welles doesn’t flinch, thinking an extra standing beside him was supposed to start the scene. On the next take he slowly slurs his line: “Aaahhhh, the … the … French … shhh … champagne.” He slumps in his seat, looking like he might fall over, as extras try not to giggle.

Paul Masson eventually had no choice but to fire Welles, though not because of his drunken lack of professionalism — rather, because he quit drinking! An ever-so-slightly thinner Welles claimed in an interview he no longer indulged on snacks or Paul Masson wine as he was on a diet. Thus, the winery moved onto actor John Gielgud, whose elegant and slender look was more befitting the Chablis they were now pushing.

“He’s doing his butler [character], from the little dwarf’s movie,” Welles cracked of Gielgud’s work in the spots, referring to his recent hit Arthur and mocking Gielgud’s costar, the 5’3” Dudley Moore. Welles was clearly hurt he’d lost the gig.

But he kept on trucking along, doing commercials for Texaco, Hayden Flour Mills, Lone Star Cement, pay-per-view TV, board games and countless movie trailers. In 1985, a few months before his death, Welles was flogging Nashua photocopiers, lending them far more gravitas than they ever deserved. In the comments thread for that commercial on YouTube, users jokingly dissect it.

“He musn’t [sic] have been willing to do many takes, it sounded like he needed to clears his throat.”

“Hey, at least he wasn’t hawking bug spray or odor-eaters,” adds another.

“This isn’t actually his last performance,” jokes one man. “he starred in a Commodore advert later for their Amiga 1200 (bundled with Pushover and Lemmings 2: the Tribes). It was called the ‘Old Sauce Collection.’”

In actuality, however, Welles was very close to having one more shot with Paul Masson. In late September of 1985, the Davis & Gilbert ad agency sent Welles a letter to see if he might be interested in reviving his spokesman duties for an upcoming 1986 campaign. It would be a one-year contract for $225,000 — half of what he had once received — and include appearances across the country, something Welles had no interest in at his old age. At a lunch on October 5, 1985 he told his friend Henry Jaglom that he had turned down the gig, for what he now called that “terrible wine.”

Six days later he would be dead.

Like Citizen Kane, however, Welles’s Paul Masson spots live on in the popular consciousness. For decades, the drunken clips were a cult sensation amongst an underground community of cineastes who swapped VHS tapes. The drunken outtakes were finally uploaded to YouTube in 2009. Since then, higher quality versions — and the actual commercials themselves — would appear on the video-sharing site.

They now have many many millions of views on YouTube and have inspired countless blog posts, influential enough to the modern-day internet to even receive an entry on Know Your Meme. They’ve likewise been spoofed by everyone from John Candy in the 1980s to the animated series The Critic in the 1990s to the Washington DC-based “quaalude swing” band The French Champagne, who named themselves after the drunken outtake.

They were even mentioned in most of Welles’s American obituaries — foreign publications were far more reverent of the great man — with Shales noting that “Welles earned so much derision for his Paul Masson wine ads that nearly every major obituary writer managed to tut-tut over it when he died in 1985.”

Of course, any Welles fan eventually realizes that all his works, big and small, are in a way about himself. And so too would scholars soon start to see that even a silly commercial campaign that he drunkenly phoned in could be traced back to his squandered movie career.

As McBride would note:

“The commercial catchphrase [“We will sell no wine before its time”] became a joke, and a signature line for Welles himself, helping to define his personality in the media as that of a hedonist who preferred to dawdle over his vineyard interminably, releasing the fruits of his labor only rarely, if ever.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.