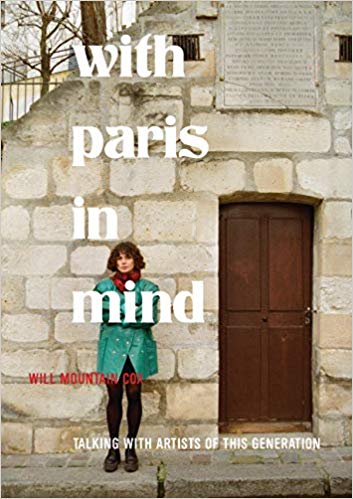

“So really, foundationally, I wanted to show Paris off as a place where things still happened,” says Will Mountain Cox. “Where there were still young artists, making good work, worth paying attention to.” He’s talking about his new book, With Paris in Mind: Talking With Artists of This Generation. It’s a collection of interviews with artists working across multiple disciplines — and a resounding retort to the argument that Paris’s days as an artistic hub are behind it.

Cox moved to Paris in 2013, fell in love with the city, and then had to leave for various reasons. His travels took him to other large cities, including London and Los Angeles, and during his time there he began to notice how Paris was being perceived. “In all those other places, the artists I met seemed to think Paris wasn’t worth much as an art center any more,” he recalls. “These opinions didn’t make sense when set against my innocent, maybe clichéd love of the place or the inspiration I had received from other young writers living there.”

He also notes that there were pragmatic reasons for Paris’s draw for artists as well. “ I always found myself returning to Paris, not just out of love, but also because it was a cheaper, more sustainable place to write and ‘be an artist,’” he says.

With Paris in Mind covers a vast amount of artistic territory. Filmmaker Léa Mysius discusses the way that memory and geography connect to the creation of her acclaimed films, while married writers Lucy K. Shaw and Oscar d’Artois address questions of travel, commitment and institutions in their interview. For Cox, this was all part of a grander design for the project. “I wanted to find a way to explore contemporary social issues in a format that wasn’t just angry political debate,” he says. “I thought it would be interesting to find artists whose work brought more complex, more personal, less polarized insight into topics like identity, sexuality, urban life, mental health; things like that.”

And for Cox, his work on the book has changed his relationship to the city around him. “I’ve found myself even more in love with these artists’ work, work I loved before reaching out, after the interviewing,” he says. “These artists populate the ‘art city,’ and so learning to think about every Paris-based artists’ work in the way I’ve thought about these artists’ work, is exciting.”

A very different take on Paris and art comes from the recent anthology We’ll Never Have Paris, edited by Andrew Gallix. From his perspective, a lot of discussion of Paris emerges from Anglophone perceptions of it. “ have lived here most of my life — in several parts of the 9th and 14th arrondissements, as well as in the 6th and 18th — and currently reside in one of Paris’s poor, rat-infested northern banlieues, soon to be subsumed into a brave new Grand Paris,” he says. “I certainly cannot be accused of labouring under the delusion that it is all glamorous boutiques and bohemian cafés. I know what the reality of everyday life in Paris is and relaying it to an English-speaking readership was not what I set out to do. Quite the contrary, in fact.”

For Gallix, the anthology became a way to explore how certain writers helped to shape enduring perceptions of Paris. “ It dawned on me that the romantic notion of a bohemian Paris that many people entertain all over the world owed as much to Hemingway and other English-language writers as to Hugo or Rimbaud,” he explains. “So I set out to explore this Anglo version of Paris. I wanted to see how the idea of Paris — whether rooted in their experience or not — inspired Anglophone writers today.”

Here, the contributors hail from a host of nations, including Will Self, Max Porter and Joanna Walsh. “I started off by approaching authors whose work I admired and who had, I knew, resided for a while in Paris, either recently or years ago,” Gallix says. “At the same time, I shunned the expat communities and in particular all those purveyors of ghastly expat memoirs. I also made sure that some of the contributors had never even set foot in France, let alone Paris, so that the remit would become a kind of Oulipian writing constraint in their case. Only five contributors, out of 79, currently reside in the French capital.”

Gallix also planned for a weighty volume from the very beginning. “I knew from the start that I wanted to produce a capacious volume that readers could dip into aboard the Eurostar or while sipping a coffee at a sidewalk café,” he says.

As for the reaction to We’ll Never Have Paris, it’s been mixed, he explains. “The book got very good reviews in the Times Literary Supplement and Financial Times. However, sales have proved much healthier in the US than in the UK despite the lack of reviews across the Pond,” Gallix says. “This is probably due to a strong sales team and good distribution. Perhaps the allure of Paris also remains greater over there. You tell me.”

Regardless of whether you embrace Paris wholeheartedly or view it with a historical remove, both Cox and Gallix are, in their own ways, demonstrating the continued vibrancy of the city and the work it can inspire. It’s not what you might expect, but it might be just the work you’re looking for.

For more travel news, tips and inspo, sign up for InsideHook's weekly travel newsletter, The Journey.