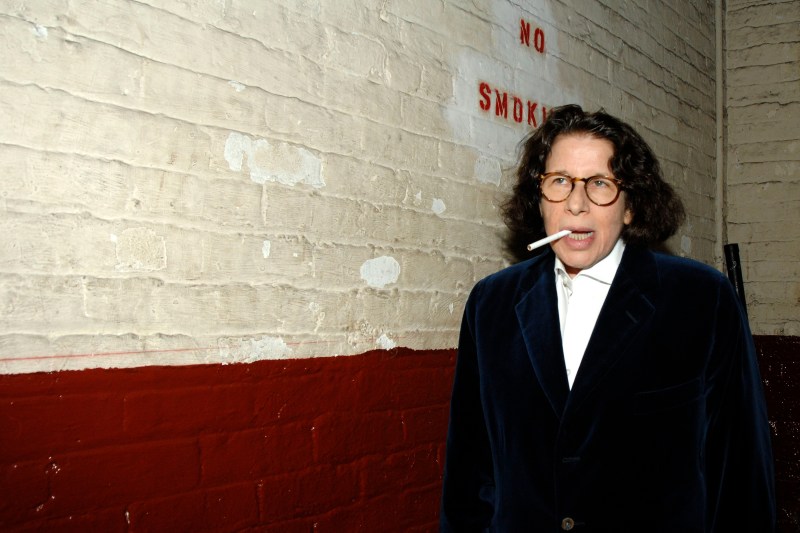

To paraphrase (and repurpose) a line from the 1977 musical Annie, Fran Lebowitz is never fully dressed without a scowl. (To extend the analogy: yes, it is a hard knock life, but no, the sun won’t come out tomorrow.) A bespoke men’s suit jacket complements the ensemble, as do blue jeans, a white button-down shirt, wingtip cowboy boots, Oscar Wilde hair, a Marlboro Light, and an air of indolence.

It’s this last quality for which she may be best known. Lebowitz is perhaps the least prolific writer of her generation—her literary legacy rests squarely on two slim volumes of sardonic comic essays published in 1978 and 1981. Writing had always been torturous for her; after her second book was released, it became impossible. A legendary, decade-long bout of writer’s block followed, and when it lifted, the words came sporadically. Since then, there has been only an incongruous 1994 children’s book (think talking pandas in Manhattan); a piercing and ever-relevant transcribed interview on race, published under her byline in Vanity Fair in 1997; and a 2006 excerpt, in the same magazine, of a long-gestating book. (She has two half-finished manuscripts; her editor declined her suggestion to combine them into one.)

But anyone who laments Lebowitz’s story as one of prodigious talent squandered has never heard her speak. Besides—perhaps beyond—her gifts for comic writing and social observation, Lebowitz is nothing less than one of our preeminent extemporaneous talkers. A Lebowitz monologue is a miracle of cogency—in a few leisurely rhetorical strides she can elucidate the knottiest issue, riotous laugh lines included. She is unabashedly nonconformist, consistently entertaining, and—to hear her tell it—omniscient. “It’s really pleasurable knowing everything,” she says in Martin Scorsese’s 2010 documentary on her, Public Speaking. “Now, I’m sure that people think, ‘She doesn’t know everything.’ But they’re wrong. I do.”

The prospect of holding one’s own in a conversation with Lebowitz could strike fear into the most intrepid heart. But, as one quickly learns, the best approach is to make the “conversation” as one-sided as possible and to prompt the digressive soliloquies she excels at. A recent phone interview found her (what else?) lively, opinionated, and—from the get-go—raring to shower the current occupant of the White House with her exquisite ire.

Do you have any thoughts on President Trump’s recent firing of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, and his nomination of Mike Pompeo as Tillerson’s replacement?

Um, of course. I have opinions on all this stuff. The thing about Rex Tillerson is, I don’t remember how many times it is [Trump’s] fired people, but it’s at least my impression that no matter how much you hated the person he fired, they seem better than the person he’s replacing them with.

I can’t even remember who this guy was, Pompeo, before Trump made him the head of the CIA. He’s probably some sort of Republican senator or something, is that correct?

He was a Tea Party congressman who was particularly critical of Hillary Clinton during the Benghazi investigation.

See, this is what I meant. He is worse than Rex Tillerson. I saw it on television, and he [Trump] does this in the most offhand way. I put more thought into trying to decide which apples I should choose at the supermarket. This is, like, off the top of his head. So, do I think this is gonna be a good thing? Nothing he does is gonna be a good thing. Everything he does is awful, as everyone in New York City knew before he became the president, which is why no one voted for him here.

What do you think of his penchant for announcing important decisions on Twitter?

What do I think about conducting the affairs of the United States of America via a thing that every seven-year-old in the United States has? I think it’s a bad idea. And it’s a particularly bad idea with him.

He doesn’t understand what the job of the president is. He has zero idea what this job is. So he conducts it the way I assume he conducted what Republicans call his real estate business, but what we know was, you know, some sort of hustle. You can only do that, by the way, if it’s an illegitimate business. You couldn’t run a deli that way. So, you know, this is how he conducts with the affairs of United States of America.

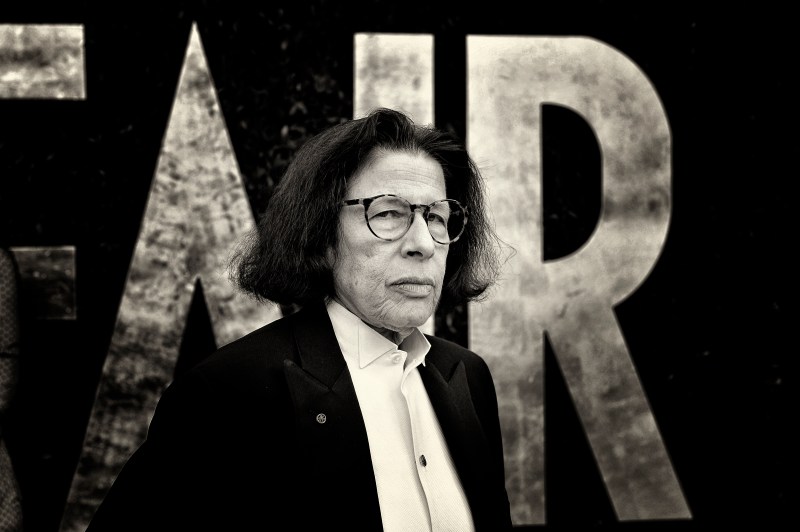

(Larry Busacca/VF13 / Contributor)

I’m certain—I mean, I am not a constitutional scholar, although I am compared to him—I’m certain that you are not even allowed to do half these things he does. I mean, I know enough to know that it is actually illegitimate—not illegal, but illegitimate—to fire the secretary of state because he doesn’t agree with you. You’re not supposed to be surrounded by people who agree with you if you’re the president. He’s supposed to have—when I say opposing views, he’s not supposed to have radically opposing views. It’s not like a Republican president has to have a Democratic secretary of state. But they shouldn’t agree on everything. It’s hard for me to imagine that Hillary Clinton agreed with Obama about everything, or that John Kerry agreed with Obama about everything, and it’s hard for me to imagine that Obama would’ve wanted that.

In our personal lives, we want people to agree with us. But there are many jobs of lesser importance than the presidency where we know that’s a bad idea.

Maybe that’s why Ivanks’s around—so she can give him a talking-to when necessary.

See, I think people’s idea of Ivanka Trump is just nuts. I think it’s delusional to imagine that she’s different than he is. I think she’s the same as he is. I mean, you can be incredibly different from your parents—but when that happens, you leave. If you really disagree with your parents—especially if your father happens to be the president of the United States—you do not support him in that way. So, I think she’s the same as he is. The same way I do not feel sorry for Melania Trump. A lot of women do, I know—but I don’t. I don’t feel sorry for any of these people. I feel sorry for the citizens of the United States of America—and, in fact, every other person in the world who’s affected by this.

I can think of at least two things you and Donald Trump have in common. You both were not fond of [former New York City mayor] Ed Koch, and you both have heel spurs.

That’s true. Okay—I am not alone in not liking Ed Koch. I really detested Ed Koch as the mayor. But I never thought of that as me being in concert with Donald Trump.

And I do have a heel spur. And let me assure you that if I had been a boy in the family that I grew up in, I would’ve gone to Vietnam with the bone spur. It’s not that big a deal. I mean, I think he [Trump] had seven deferments [he had five]. Here’s what a heel spur is: it’s a little piece of calcium. So sometimes it hurts to walk. It’s very hard for me to imagine that the United States Army would’ve cared if the boy version of Fran Lebowitz sometimes found it painful to walk. People went to Vietnam with far worse things than that. It was a matter of money—his father got him out. It’s so interesting to me that someone who loves war so much and adores the military so much gave up all those opportunities to serve.

You’ve predicted that Trump will resign before his term is out due to fear that special counsel Robert Mueller will discover financial improprieties of his. Let’s say this happens. Would you rather have Trump or Pence?

Pence. And I’ll tell you why. I really believe—now, I have to preface this by saying that I was incredibly wrong about the election. I spent the year before the election going around the country telling, probably, an aggregate of thousands of people, “don’t be ridiculous, he has zero chance of winning.” And I absolutely believed that till, like, the last second. So, I have to say I was extremely wrong about that, so I would understand if people do not find my prophecies about Donald Trump credible.

First of all, I don’t think he loves this job that much. I think he likes certain parts of it—where he gets to, like, talk to generals. He’s like the world’s worst six-year-old boy. You know, “Look at me, I’m talking to these generals…” I tell you, I am sick of seeing these generals. It’s like a Marx Brothers movie. So, I think that if Mueller gets close to his money, he will leave, because I don’t think that he’ll wanna go through it. This whole thing is about money for him, by the way. He has no ideology. He doesn’t believe any of this stuff. He doesn’t believe when he says we should have gun laws, and then he doesn’t believe when he says we shouldn’t have gun laws.

But that’s the difference with Pence—he has an ideology.

Yes, but because he does have this ideology, which is grotesque—I mean, Mike Pence’s ideology is grotesque—I do not believe that he could win a general election. That’s a niche market. Because his ideology is almost entirely about the oppression of women. There’s really almost nothing else there. There are certainly a lot of people who believe in that, but there are not enough. So, that’s why I would prefer to have Pence—because he could not be re-elected.

Whereas with Trump, you never know. I don’t believe he could be re-elected, but I would think he has more chance. Because Trump doesn’t have—you know, people talk about his “base” all the time, and I always feel that that word is used in its every sense—but he’s like a cult figure, Trump. He’s not like a politician. He’s like Jim Jones. His support is emotional. When you watch those rallies—you can watch them now, he still has campaign rallies—but before the election, when I saw those rallies, someone of my age, the first thing I said was, “These are George Wallace rallies. These are Klan rallies.”

The people who voted for him—I know you’re not supposed to say this, I know that Democrats are supposed to lure these people to our side, but I’m not one of those people—I believe that his support is almost entirely racist. I don’t believe that the majority of them really believe he’s gonna make it 1955 again, and reopen the coal mines and bring back jobs in factories that pay $35 an hour. I don’t think they believe that, ‘cause they’re certainly smarter than he is, because who is not? But I certainly believe that what he allows them to do is express this bigotry that they’ve had to tamp down all these years. And I think that that obviously is so valuable to them that they’ll vote for him.

Okay. Enough Trump. In your recent interview on Australian television—which was very amusing, by the way. You met a baby kangaroo, and were a bit standoffish.

A., I don’t like animals—even regular animals, like dogs. And B., I am afraid of them. I’m not particularly afraid of pets, but I could live without them. A kangaroo is a wild animal. That is why the guy who brought that kangaroo there, and also two other wild animals—a koala bear and some kind of an incredibly scary bird—has something called a wildlife refuge. The guy kept saying, “Isn’t he cute, isn’t he cute?” And they are kind of cute. But so is a picture of them.

The first thing I noticed was these incredible claws this animal has. And then the kangaroo did bite the host of that show. She was quite calm when the cameras were rolling, but then she raced into the bathroom to check her bite. If that kangaroo had bitten me, I would not have been calm while the cameras were rolling. But also I thought, what would I have done? I would have had to go back to New York and call my doctor, who’s a brilliant doctor, and say to him, “Who’s the best kangaroo bite doctor in New York?” And for the first time I would have stumped him. Because there is no such thing here. So yes, I was very standoffish, because I was afraid of this animal.

If you have a kangaroo bite, I can give you the name of a very good doctor.

A kangaroo bite doctor? Yes. The important thing when traveling is to not get any bites or viruses or infections that we don’t have here. Because then they can’t fix them. This has happened to me.

In that interview, you expressed amazement that the discourse on sexual harassment changed so quickly. What do you think finally lit the fuse and reset the conversation?

This is another thing I would never have predicted. And that is what I meant: this is the way the world is. This is the way the world has been for literally tens of thousands of years. So there was no reason to assume it was gonna change. I think it was a confluence of the events, some of which are less apparent than others. The thing with Harvey [Weinstein], for instance. I know Harvey. I heard a million stories about Harvey. I never heard these stories of violence. I never heard rape, ever. But I heard the usual stories that you would hear, of what I would describe as, you know, the movie business.

Once that [the accusations against Weinstein] happened, it was like an avalanche. I was astounded. There was a period where every day it was a different guy. And I was just waiting till it was a guy that I didn’t know. And then it kind of stopped. I’m certain there are dozens—hundreds—more guys.

You’ve expressed surprise that women are no longer tolerating this behavior from men. To clarify—I assume you think this is a good thing.

It’s a great thing! I can’t believe this good thing happened! I don’t ordinarily say things like this, ‘cause I don’t really think them: men do not understand this. You cannot explain to men what it is like to be a woman. You simply can’t. Because you’re not just explaining what it’s like to be a woman, you’re explaining what it’s like to be a girl. You’re explaining what it’s like to be a baby girl. Listen to the way people talk to babies. The tone of voice that people use to a baby girl is different than to a baby boy. So that is from the second you are born. You absolutely cannot convey this to even the most brilliant, well-meaning man on the planet. Some of whom I know. But I have been unable, ever, to explain this to men.

It is a great thing that I never expected to happen. Because A., I never expect great things to happen—because, let’s face it, they hardly ever do—and B., this particular thing is rooted in not just bigotry or stupidity the way, say, racism is, but also in biology. This is a thing that is so deep in humans that it would be impossible for me to imagine that in any way it would’ve been alleviated. But this is a fantastic thing—I could not be more supportive, or more surprised. And usually, surprises are bad.

There’s a book on Sue Mengers that relays a story about you, Mengers, and David Geffen. Mengers is recounting horror stories from her early days in Hollywood. Geffen says, “I can’t believe it. Didn’t anyone see your talent?” You say, “You have zero idea what it’s like to be a girl. Zero.”

That’s right. And, of course, Sue—if she was alive, which I wish she was—would be well into her eighties now. So, when Sue was a girl, it was a billion times worse—a billion times worse. And she was in show business—which has, by the way, always been one of the worst. Because these businesses are really based on sex. It’s bad for women in every business, but not every business is selling sex. Sue had stories that were hair-raising even to me, let alone to David Geffen, who was a man. David was really surprised by it. But I was not.

I know that you’re loath to draw imprecise analogies between marginalized groups. But it seems that the advantages men enjoy parallel a certain advantage you mention in your 1997 Vanity Fair piece on race. In it, you say, “… by the time the white person sees the black person standing next to him at what he thinks is the starting line, the black person should be exhausted from his long and arduous trek to the beginning.” If whites are ignorant of the advantages they enjoy, it’s because they’ve never not had them. They’ve never, for instance, had a clerk at a convenience store watch their every move. Or worse.

Yes. But I do believe—I know this sounds optimistic—I believe that racism could end. I don’t believe it will, necessarily. But I do believe it could end, because it is a total fantasy of superiority. It’s literally the color of someone’s skin. There are absolutely zero differences between human beings of different skin colors. But there are vast differences between people of different genders. And that’s why I don’t think that it’s comparable to women. And it’s not comparable to being gay, either, which is a very different thing—a third thing. The thing about bad things: they come in many varieties.

But I find it, by the way, equally hard to explain to people who are young what it was like being gay when I was young. It is almost as hard as it is to try to describe to a man what it’s like to be a woman. And I suppose that might be true of black people and white people, but I think it might be less true because it’s so—of all these things, racism’s probably the stupidest. By which I mean, it just has zero to do with anything.

Growing up in a small town in the ‘50s and ‘60s, as you did, what was your exposure to homosexuality? Did you have any gay friends?

There was no such thing—this is what I can’t explain to people. I was born in 1950—I’d like to point out, the end of 1950, so I’m 67 now, not 68, as you might have decided. It didn’t exist. You never saw it. Of course, it must’ve existed, but you never heard about it, you never saw it, there were zero images of it—not just in the culture, but in the world. If I had not been such a bookworm, I would never have heard of it. And I know women who are my age who were not such bookworms, and who lived in even more culturally deprived places than I did—women especially—who, when they noticed this in themselves, thought they were the only person in the world like that. And that was a pretty common thing, by the way. And that could never happen now.

Were you grappling with that [your sexuality] while you were still at home? After you moved to New York?

Oh, no, no. I mean, I can’t really remember exactly when I first realized I had, like, crushes on my friends who were girls. But I probably was…12. I’m guessing about this—not that there’s anyone to counter this argument. As I said, I knew about it from reading. I have a very vivid memory of myself in the backyard of the house that I grew up in. I was reading—I don’t think I was reading about this, [but] I was thinking about it. And I remember exactly the thought that came into my head at the age of 12, which was, “Well, I guess if there is such a thing as lesbians, I guess someone has to be them, but why does it have to be me?” Because what I knew was that I would be thrown out of this life. That I could not live in this world—which, by the way, other than that, I quite liked.

Let’s talk about talking. You love to talk, and you get paid to do it. Who are your favorite talkers, past or present? Who do you most love to listen to talk?

Huh. [In terms of] watching people talk, I would have to say James Baldwin. James Baldwin was the first person I ever saw on television who I heard talk like that—by which I mean, he was the first intellectual I ever heard talk. And that’s because that’s the sort of person they used to have on television. It’s unimaginable that that sort of person would be on TV now. And I was just flabbergasted. That made me read him—I had never heard of him before then. I would say that I was probably 12 or 13 when I saw Baldwin on TV.

I also [liked] Gore [Vidal], who was also on TV. Although I didn’t obviously agree with him, I liked seeing Bill Buckley talk. Although when you see reruns of Bill talking, and you see it out of its time, it’s shocking—what people could get away with then. Of the people that are alive now, Wally Shawn is a fantastic talker. I hate when people ask me questions like this, because then I leave people out and then they get angry. I’m sure there are many others, but, at the moment, none spring to mind.

What, to your mind, is the difference between inspiration and craft in writing?

Well, I don’t even think they’re related, frankly. Inspiration is just something that comes to you—that’s what it means. Writing—I do, obviously, find it immensely arduous. My editor—who, whenever I introduce him as my editor, always says, “easiest job in town”—he says that the paralysis I have about writing is caused by an excessive reverence for the written word, and I think that’s probably true.

But part of writing is slowing down thinking. Because thinking is just something that happens, like inspiration, which is why I can talk—because I don’t have to think about it. And writing is work, which I loathe. So part of it is just sloth. And part of it is that a lot of people think that these things are connected, but I do not see that they are. I mean, what you have to know to write is very different.

I’m sure you know the world is now filled with these writing schools. There are hundreds, probably, of these graduate programs in writing, which I think are the scam of the Western world, because you cannot teach this. Talent happens to be the most random thing in the world. It is randomly sprinkled throughout the world. You never know where it’s gonna hit. You cannot inherit it, you cannot work at it, you cannot summon it.

You’re appearing on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon tomorrow night. You were also a frequent guest on Late Night with David Letterman in the ‘80s. How do Fallon and Letterman compare?

Oh, they’re completely different. I wouldn’t even think they were in the same profession, although I know they are. I mean, no one would ever describe Letterman as adorable. Jimmy is adorable. First of all, he loves his job. He has fun. He’s just—he’s cute. He really has a good time. Letterman never gave the impression that he was really enjoying himself. Also, his show, especially at the beginning, was really more of a parody of a talk show than a talk show.

Do you think Letterman was an ironist?

You know, that kind of irony, that show business irony that then became the popular culture for 25 years, is a kind of wrong definition of irony. It’s not really irony. Real irony, you don’t get rich.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.