Ken Burns is one of the most prolific documentary filmmakers of his generation and the defining voice on American history in the annals of contemporary pop culture. From The Civil War to baseball, his frequent collaborations with PBS approach each subject with an insatiable curiosity. In an age of diminished attention spans, the films he makes are epic both in execution and run time. His latest offering, Hemingway, looks at the great American writer’s legacy not only as a journalist and literary icon, but also as an almost folkloric figure who embodied — or at least claimed to embody — many of the qualities that came to define masculinity in the 20th century.

Charles Thorp recently spoke to Burns about his new three-part series, available now on PBS. Their chat below has been edited and condensed for clarity.

When did the idea of doing a documentary on Ernest Hemingway first come to you?

This has been a project decades in the making, first coming to our minds in the 1980s. Since then we have had it ready and waiting until the 2010s, when it really started coming together, with the first bit of filming happening around 2014.

What drew you to Hemingway as a subject?

I was drawn to his legacy as one of the great American writers of the 20th century. Drawn to his outrageous personality, which was largely of his own construction. The mythology of Hemingway, if you will. There were new research, scholarship and biographies that suggested a much more vulnerable and complicated person behind all of the masculine bluster. All of that, along with the greatness of the writing, compelled us to try to understand him a little bit better than we thought we did.

What of his work did you read earlier in life?

I had read The Killers at the age of 15, which was extremely disturbing to me. The implied violence. The language. The menacing thugs in the diner and the scenes from the flophouse where they are warning one of the patrons that they are being pursued. The fact that he is not running away, and the implication that he is going to be killed. I couldn’t process all of that. It was completely overwhelming.

I then found later in high school The Old Man and the Sea, which it seems like everyone at that age read. As an adult I worked through what people would consider his more important novels like The Sun Also Rises, For Whom the Bell Tolls and A Farewell to Arms. During the course of this project I spent a lot of time reading his short stories, and realized what incredible literary treasures they were. They are spectacular, dazzling pieces of writing. I then started dabbling more into his non-fiction like A Moveable Feast, Green Hills of Africa and Death in the Afternoon, which was about bullfighting.

How do you go about making a documentary about a character as large as Hemingway?

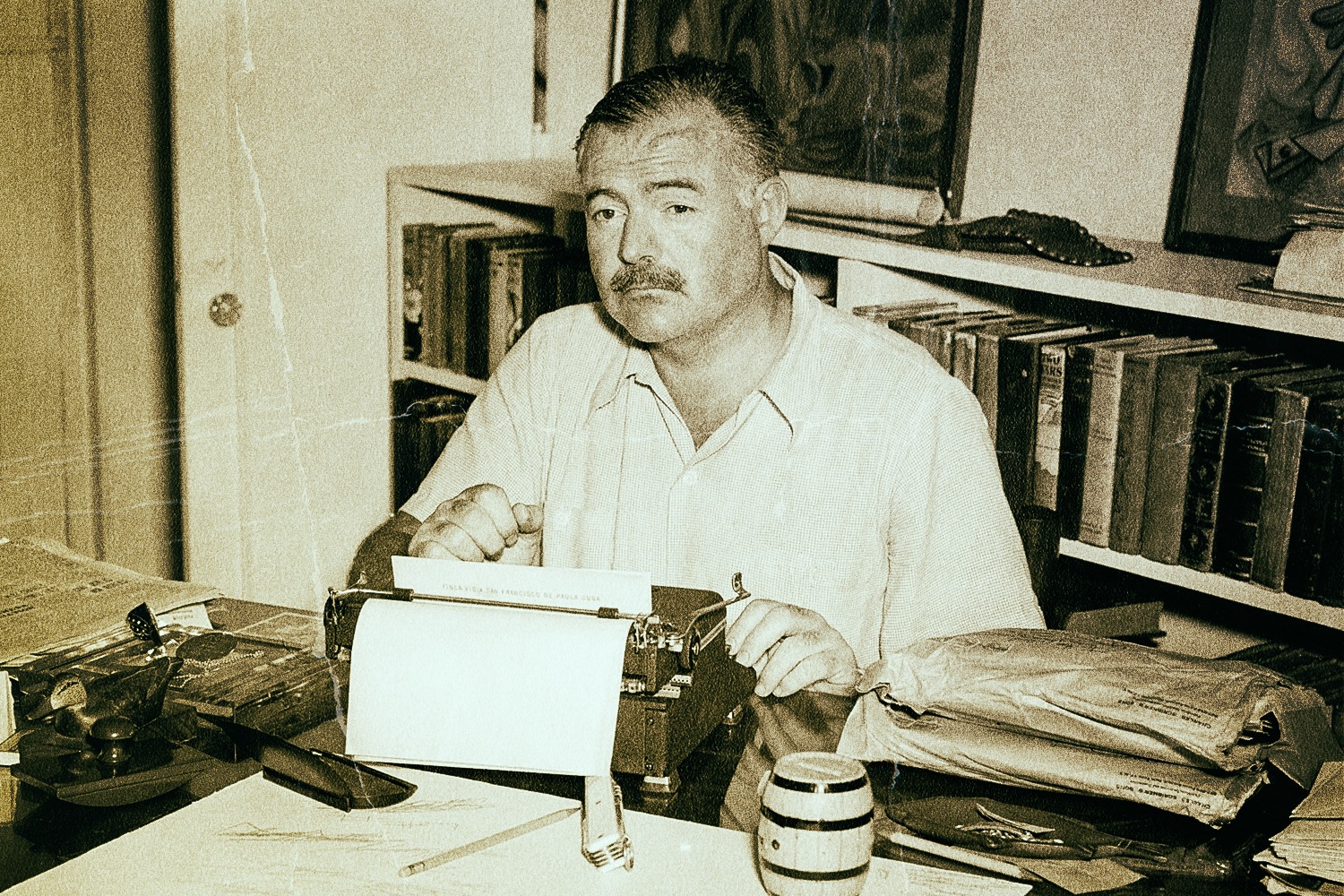

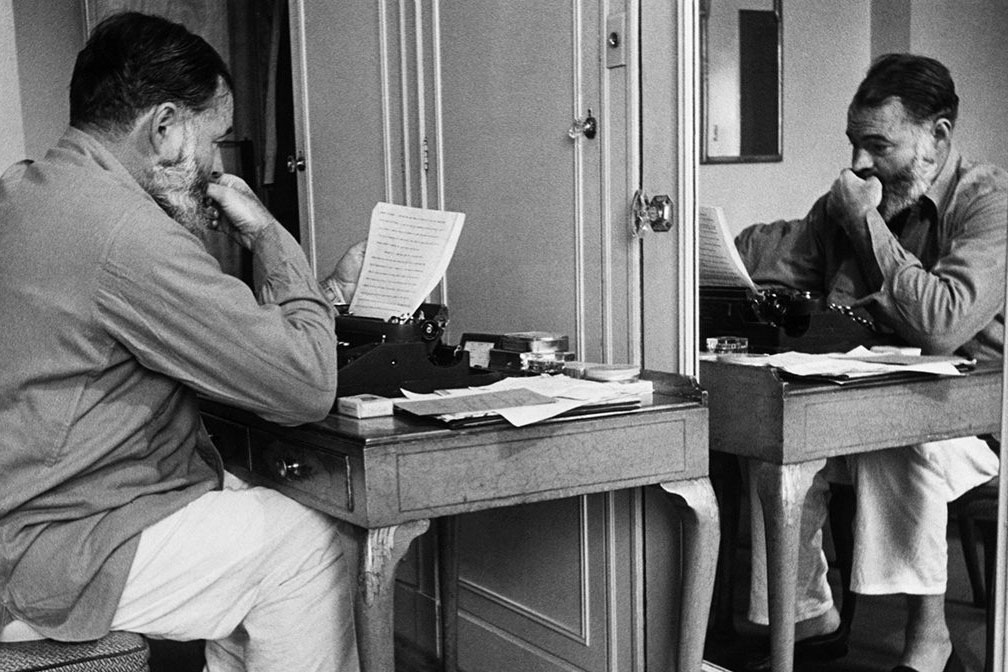

For us making this film was sharing our own personal six year process of discovery about this man, as opposed to trying to tell the audience stories that they already know. We aren’t looking to be pontificating documentary filmmakers, but instead go in with the pure spirit of research, visually of course. For that we use photographs, news reels and home movies, as well as the manuscripts that we got access to.

What did those manuscripts and letters tell you about Hemingway?

The letters give us a different side of Hemingway because these weren’t written to be published pieces, they were instead meant for lovers, wives, children, literary colleagues and enemies. Because they are less polished and disciplined, you can sense that raw emotion. You start to see insecurities behind his masculine facade, and you see the empathies that he has.

Having access to his manuscripts, we can see those 47 other endings of A Farewell to Arms that he jettisoned. See how he was also this painstakingly critical self-editor. And through those notes, see how he worked to make his writing sparer and sparer and sparer.

Do you believe there are further chasms between what the public thinks or thought about Hemingway and perhaps how he truly was?

You find him beloved all over the world, while many acknowledge how toxic that masculine image was. He was an outdoorsman, in a good way. He was a deep-sea fisherman. He was also a brawler, a drinker and a carouser. He has an inexcusably misogynist reputation but he has these short stories that are incredibly sympathetic for the woman’s point of view.

Edna O’Brien, the Irish writer who we spoke to for the film, said that that is indicative of his ability to get under the skin and adopt a kind of androgyny that helped him understand. There is kind of a self-critical element to that writing.

He struggled with his alcoholism. That is a terrible thing. Ernest Hemingway is a classic example of the destruction possible from it. Not just to yourself but to other people, through collateral damage. There is lots to be repulsed by, and react to negatively to, but then there is the literature which is some of the finest you will find. I believe this is also the benefit that these larger than life characters provide us, they are our own foibles written large. It is easier to see the flaws in Ernest Hemingway than it might be to see them in oneself.

How destructive do you think his own persona was to him while he was alive?

I think that lore turned into a wearying, bold-faced celebrity that taxed him heavily. And it make it hard for him to do the great work that was the hallmark of his disciplined earlier years. That is its own tragedy.

You combine that with a human being who is born into a family with a history of mental illness, and whose father commits suicide. Who has PTSD from being wounded and almost killed, convalescing for months during World War I. A man who by our counts had somewhere around nine serious head traumas, concussions which could have caused CTE leading to dementia or suicidal thoughts.

All during a time when the stigma around mental illness was very great. There was nobody who he was going to ask for help and no-one who would have known enough to get him any help. This all lead to a colossal tragedy at the end for this extraordinarily important writer.

The film dives deep into his time as an ambulance driver during the war, and the horrors he witnessed. Do you think that is behind some of the macabre in Hemingway’s writing?

I think it is one of those experiences that formed who he is as a person, like we are all built out of our histories. Much of his writing was curious about death, and it’s a subject that is captivating to many writers. The rest of us would rather ignore the fact that none of us are getting out of here alive. When you have a writer like Hemingway whose writers exist in the moment, a kind of existential moment, that is incredibly powerful.

That can be seen in his work like The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber, one of his more famous short stories, happens in a nano-second between his exposition of courage and his wife blowing his brains out. And then you have The Snows of Kilimanjaro where you have a dying man on safari and you have the presence of death getting closer and closer.

Or even the little boy Nick Adams in Indian Camp, one of his most powerful stories, where this night of horror occurs while he watches father give an emergency Caesarean section with a pen knife, and the husband of the pregnant woman who kills himself as he feels so helpless. After, the boy has this moment of peace rowing the boat back across the lake with his dad, following this horror that has just occurred, and it is one of the most hauntingly beautiful passages I have ever read.

What do you think is the mark that Hemingway made on writing today?

I think that while Mark Twain is the inventor of the New Journalism, Hemingway could be considered an early version of the Tom Wolfes and Hunter S. Thompsons. For the film, we wanted to speak with an international cast of writers to see his long-ranging affect on literature. As one person in the introduction of the series says, you have to either kill his ghost or embrace it. But no matter what you do you are going to be in relationship to what Ernest Hemingway did before with his short stories and his novels.

Hemingway was a great adventurer, and lived many places. How important was it for you to get footage or visit some of those properties and cities?

I would certainly say that it was important for us to visit his Oak Park house, which we did through archives, and look at his life in Paris, which we did through archives. As well as going to these places where he lived and worked in person. We wanted to show rooms where these stories were written, and see the typewriters that were being used.

My co-director Lynn [Novick] took a crew to Cuba to his Finca Vigía farm outside of Havana, a place that he left not expecting to never return again. So the home is how he left it with the bottles of alcohol half drunk, his records strewn around the record player, and little notations of weight noted in pencil on the wall by his scale in the bathroom.

The footage that we were able to capture really informs us of who this man was, as it was the place he lived the longest — nearly 20 years. For anyone interested in preserving this place, which is very special, there is a Finca Foundation out of Boston that had made it a mission to keep the place as intact as possible. We were able to get special clearance to film there, but they have mostly closed it to the public, as things were being taken from the home.

Do you find the way that he lived or the way that he writes about places inspiring a wanderlust in yourself?

Of course. That is one of the great gifts of Hemingway. He was an amazing observer of nature. You want to go to upper Michigan and fish in a stream. He went on these amazing safaris. He went to the bullfights. He lived and wrote in Paris. All of these things you want to recreate for yourself. I think I am most inspired by his travels in Africa, and was planning a trip out there, not necessarily because of this project. That had to be canceled, but I am hoping to get it rescheduled soon.

How has your opinion on Hemingway changed if at all through the process of making this movie?

I don’t think there is a final judgment that you can make. We live in a society that seems to think there is a big on and off switch; there is not. Hemingway is a hard man to get to know, a hard man to reject and also a hard man to accept. But his literary work stands on its own. I still have a book of collected short stories on my desk which I will back up at least once a week and revisit. I am always stunned at how masterful they are.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.