Stefano Ricci is fiddling with the lighting. “I designed this store with our architects as the template for all of our future stores but it’s always good to see it for real for yourself,” says the Italian designer of his new Madison Avenue flagship store in New York. “And I already know we have to double the lighting. Lights are always the most important thing with a clothing store. You have to see what you’re buying. It’s a little bit dark in here, but that does feel very Italian.”

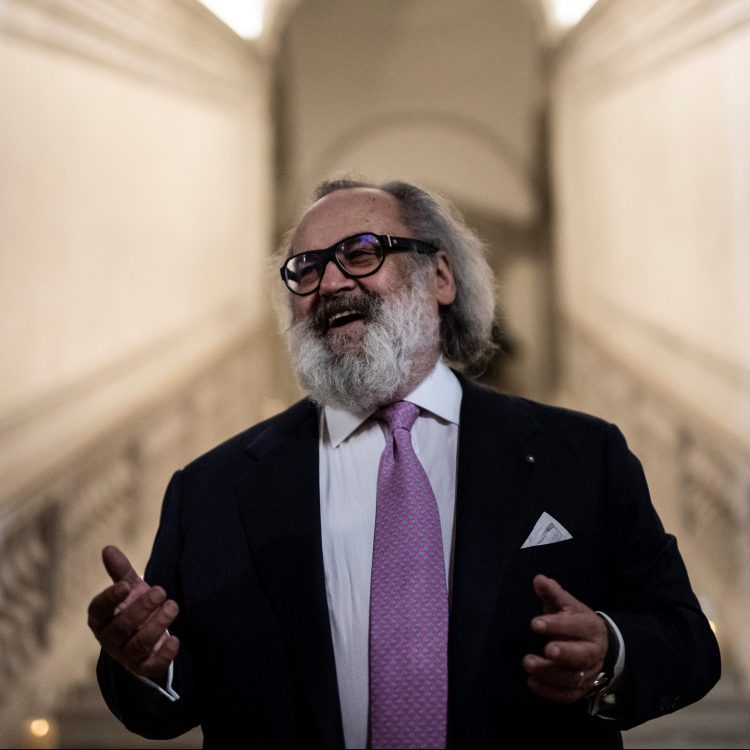

Ricci may not be as well known as the Versaces and Armanis, or the Dolce & Gabbanas — “I wouldn’t say we’re famous because that’s for the brand phenomenons, and we are normal people,” he says with a chuckle — but he is very Italian. He’s a stylish, rotund, avuncular, Karl Marx-ish figure who smokes cigars and races vintage sports cars, and who, 50 years ago this year, launched a tie company with his wife, the matriarchal power behind the throne, that would grow to become the go-to menswear brand for the very discreet and very well-off. Think CEOs and presidents and oligarchs.

Earlier this year Ricci marked that occasion by hosting a catwalk show, fantastically stage-set in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, naturally, spectacular in a way that perhaps only an Italian like him could worry was insufficiently razzmatazz. “Was it too much, or could we have done it better?” Ricci asks, with genuine concern. He has recently passed control of the business to his two sons, Filippo and Niccolo — that’s very Italian too — and it remains one of very few luxury brands that is entirely family-owned. Not that Ricci thinks much of the word “luxury.”

“I’ve always found Egypt and its archaeology just so inspiring. I think it was when I went to Egypt 20 years ago that I was asked what my definition of luxury was and had a real moment of awakening,” Ricci recalls. “I said that real luxury was a glass of cold water in the desert; it’s family and love and friends. And having a job. It’s basic stuff. It’s not really about clothing. I think round about that time was a turning point too in that suddenly everything was being called “luxury.” The term was abused such that it lost any meaning. It was all commercial, commercial, commercial. Most of my competitors [as were] are now looking for low cost, high volume and high profit.”

Indeed, Ricci has survived, and thrived, quietly in the background by sticking — almost bloody-mindedly — to his quality mantra: “I’ve always believed that quality just doesn’t come with quantity,” he says. “Really, we’re just a little artisan company from Florence. That’s always been the mentality even as we’ve grown. We have people who have worked with us for 40 years, who are coming up to retirement and we’re trying to get them to pass their knowledge of many years on to those younger people we can find who are interested in learning a craft. But finding those young people isn’t easy. They all want to become rich without working. Thanks to social media, they think that’s the world, but of course it isn’t.”

It’s not just about the quality. Stefano Ricci products are only available through Stefano Ricci’s 73 stores. The company only recently signed its first license deals — for cigars and watches; Ricci could have been a very, very rich man long ago making Stefano Ricco tea towels and soaps and opening hotels. And even those products are only available through his stores. His clothing never goes on sale. He never does celebrity endorsements because, he says, his customers know that’s all BS.

The clothing — every stitch of which is made in Italy — isn’t radical in its design, and some of it can lean towards the glitzy: belt buckles in solid platinum or crocodile-skin sneakers, perfect for “people successful through the new economy who want to express through their clothing that they’re winners,” Ricci concedes. “And [sometimes] that can lead to ostentation.” But in its cloth, construction, lightness and comfort, it’s legendary menswear. At least among the few who can afford it.

How a British Designer Recreated an Iconic “Goodfellas” Fit

Through tireless sourcing and exacting replication, Scott Fraser Simpson has resurrected two of Henry Hill’s most iconic looksAll the same, that has made for a tidy $200 million turnover and some truly dedicated fans — like the businessman who Ricci’s tailors followed around the world for six months, showing him fine fabrics and taking measurements without actually taking any orders. And who then, one day, announced that he was satisfied with the product and service and signed on the line for 50 suits at $10,000 a pop.

“Our customers trust us to only offer the very best — and we have to, given the prices we charge. That’s just a mark of respect for the customer — that the price is, we think, always justified by the materials, the finishing and so on,” Ricci explains. “That means there’s something of an arms race going on, and every season we have to push ourselves a little further. After all, our clients don’t actually need more suits, or more jeans, or more anything. Of course the look is important, but this is really about a philosophy of manufacture.”

It’s also come about as a result of some very smart — or bold — business decisions. Ricci’s company used to also make for other brands, but he decided, one day, that this had to end so he could focus on his own products — and so gave up 85% of his turnover overnight. Despite people telling him he was mad, Ricci was, back in 1991, one of the first luxury designers to open stores in China, “and this was when there were no clothes shops there, when there was barely even lighting in the streets,” Ricci says with a laugh. Now he’s a major figure with China’s establishment.

“Even now I have people telling me all the time that if we use machine stitching on such-and-such a jacket, or a lesser grade of leather, or a certain zip, we could sell 50 times more of them. But that world has no pleasure in it for me,” he adds. “But this approach that we took with the menswear market those decades ago probably wouldn’t work if we were starting out now. The competition today is dramatic. You need huge capital. And [that’s why] I’ve not seen any brand I admire come up over the last two decades and actually stay in the market for more than just a few years. They come, and they go.”

Ricci is now in his 70s and is dialing back his own involvement in the family firm. He’s had offers to sell up and always declined, but is content that in time his sons may choose differently. “My duty has been to pass the company — and the spirit of the company — on to my kids. And, honestly, it’s not all about money. I’ve never met anyone who’s happy just because they can sit around counting money.”

But he says the enjoyment of fine things — without ever forgetting that they’re just things — has stood him in good stead. “It’s an approach I’ve stuck with for 50 years and it still seems to work, though I certainly look at myself now and feel much older,” he says. “My wife, of course, looks just the same. She’s laughing at that and shaking her head.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.