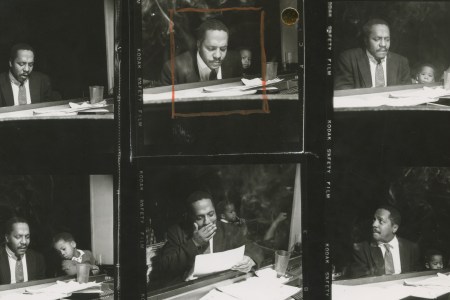

“He seems to be willing to try anything,” Amiri Baraka, then LeRoi Jones, wrote in a 1959 Jazz Review profile of Wayne Shorter, concluding, “He usually makes it.” That ambition and wide scope makes it all the more challenging for a novice to find an entry point into the late jazz giant, who passed away at 89 earlier this week. In conversation, the saxophonist and composer was noted for his pleasant unwillingness to stay on any one topic; musically, he was similar, resisting over and over the temptation to keep rehashing his youthful creations to please audiences. The results were enormous, a canon all their own that lovingly demand repeat listens and, for jazz aficionados and students, careful study.

Below are a few key records in Shorter’s vast discography, which is even more vast when one considers all his excellent work as a sideman. But Shorter, with all his curiosity and whims, would want you to resist the temptation to be too dogmatic or linear — so use this as a jumping off point, rather than a checklist.

Night Dreamer (1964)

On Shorter’s first album for Blue Note, there’s a real romance to his characteristically unforgettable melodies. “I’m playing more emotionally than I used to,” he told Nat Hentoff for the record’s original liner notes. “When you get down to fundamental emotions and relationships, there’s no need to rely excessively on technical devices.” Nevertheless, the technique of Shorter and his collaborators simmers on this record — trumpeter Lee Morgan, pianist McCoy Tyner (presumably on an off-day from his ongoing gig with John Coltrane), bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Elvin Jones come together to extraordinary effect, all mid-century swing and sophistication.

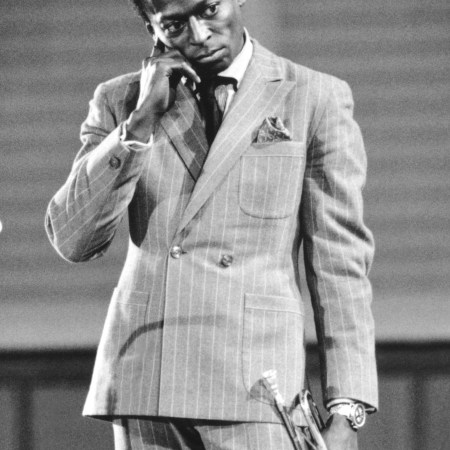

Nefertiti (1968)

Shorter was a member of what’s often called Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet, the (first) injection of youthful talent brought on to push the already legendary Davis towards fresh sounds (and bolster their own reputations in the process). Almost immediately, Shorter — along with his bandmate Herbie Hancock — became invaluable to the ensemble not only as an instrumentalist but as a composer. Here, on Davis’ final acoustic album of his career, Shorter is responsible for half of the tracks, including the meditative title composition. “Nefertiti” includes no horn solos, just Davis and Shorter playing the same melody over and over as the rhythm section improvises underneath — a sort of musical foreshadowing of Shorter’s later Buddhist practice.

Heavy Weather (1977)

Putting Shorter’s work with Weather Report adjacent to the seductive, warm sound of his ’60s Blue Note albums is always a little jarring — and yet, that’s precisely why it’s important. Shorter, like so many musicians, didn’t want to keep making the same music forever, which is precisely why he sought out electrified funk fusion with his Weather Report bandmates. Backed by a bevy of synths and a rich array of grooves, Shorter jammed through the group’s heavily orchestrated tunes — and people loved it, proving that jazz could still go platinum. Weather Report’s bass phenom Jaco Pastorius and keyboard player Joe Zawinul added a whole different array of colors to Shorter’s compositional palette, which he put to use on the slow-burning “Harlequin” and the fiercely groovy “Palladium.”

A New Documentary Explores the History of Blue Note Records

Sophie Huber’s Film Traces a Musical Legacy From Miles Davis to Kendrick LamarAdam’s Apple (1967)

When this album was released in the late ’60s, the jazz world was in one early iteration of its ongoing debates about whether popular music is a fitting source of inspiration for the music, with its ever-more-esoteric aura — a debate rooted in a skepticism of whether any music that’s popular can actually be good. Here Shorter bypassed the debate altogether with “Footprints,” whose earworm chorus helped make it one of his best-known compositions. Who needs an assist from a pop-minded songwriter when you can conjure their magic over complex, African-inspired rhythmic interplay that today, every aspiring jazzer must master as a rite of passage?

The looseness of this quartet gives it an ever-modern feel; step into any contemporary jazz club and you’ll hear that, very often, this sound is the one that the players are reaching towards more than a half century after it was released. It is subtle and gentle, as the original liner notes explain well, but no less forceful for its lack of overt bluster; Shorter’s quiet confidence owns the day, as his stellar support fall in swinging, sensitive line.

Native Dancer (1975)

At his wife Ana Maria’s suggestion, Shorter tapped Brazilian singer-songwriter Milton Nascimento for this album — yet another broadly influential collaboration. Like the Weather Report projects Shorter was working on simultaneously, Native Dancer has a decidedly fusion flair (which Herbie Hancock, by this point a long time collaborator, happily joined in creating). The band of Americans and Brazilians, with Ana Maria (who was Angolan and spoke Portuguese) as a translator, put together this collection of inventive, haunting songs that feel grounded in some place beyond their creators’ homelands. Esperanza Spalding has cited it as an influence, one example of the genreless, deeply spirited music that this collaboration helped inspire.

Speak No Evil (1966)

Arresting from its opening riff — the most self-assured and collected battle-cry you can imagine — this album has become one of contemporary jazz’s cornerstones thanks to both its all-star cast and enduring melodies. It is impossible to pick a standout track, because Shorter’s compositional and improvisational creativity overflow on each one. After only a few listens, you might find yourself humming along not just to the compositions’ written choruses but Shorter’s solos as well simply because they sound so easy and organic.

Shorter and his team — trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Elvin Jones — flow together as one effortless, evocative, fiercely emotional musical unit. From the deceptively simple swing of “Witch Hunt” to the stuttering, surprising “Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum,” from the incisive title track to the stunning, ballad “Infant Eyes,” it’s not just that there isn’t a dud in the bunch. It’s that Shorter and his collaborators were able to manifest an extraordinarily ambitious and eminently listenable new vision of what music can be.

“From here on, I’m trying to fan out, to concern myself with the universe instead of just my own small corner of it,” as Shorter put it in the album’s original liner notes. That begins to explain, then, why Speak is the kind of record that will have you ready to throw the rest of your collection away, and be nearly justified in doing so — you can hear, for just under 45 minutes, a slice of the whole universe.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.