What does Pearl Jam mean in 2022? In the 1990s, they were one of the world’s biggest bands, riding an alternative-rock wave that also included Nirvana and Soundgarden, but by the end of that decade, Eddie Vedder and his cohorts were far from fashionable, their earnest, anthemic sound replaced by rap-rock and boy bands as the zeitgeist’s dominant sounds. Forged in the wake of the overdose death of Andrew Wood, the charismatic frontman of Mother Love Bone — a Seattle band that included future Pearl Jam members Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament — Pearl Jam don’t record as much as they did in their heyday, but they remain a popular touring act. They have survived and thrived, even if the scene they came up in has faded away and the group’s cultural relevance has greatly diminished.

Steven Hyden, Uproxx’s Cultural Critic and the author of critical analyses such as Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me, was 14 when Pearl Jam’s era-defining debut Ten came out — the perfect age to embrace the band’s songs of alienation and guarded hope. As Hyden grew up, so did Vedder, and although Hyden’s interest in the group sometimes waned, he found himself later reconnecting with the older, more mature frontman — not to mention a band that had weathered hard times and come out the other side intact.

His new book Long Road: Pearl Jam and the Soundtrack of a Generation is an examination of Pearl Jam, but it’s also a look at how they shaped Gen X kids like himself — how Vedder was an extension of the 1990s in all their idealism and shifting political viewpoints. Hyden is clear-eyed about Pearl Jam’s strengths and weaknesses — their fallow periods and their underrated records — but the book is also quite personal, the author infusing his own memories of coming of age at a time when Vs. and Vitalogy provided the soundtrack. The book wrestles with the question of why Pearl Jam mattered — and why, to some, they still very much do.

Speaking from his Minnesota home — and, appropriately, wearing a plaid shirt — Hyden opened up about writing such an emotional book, which is divided into chapters that are each devoted to a specific Pearl Jam song. We also talked about the death of idealism, the pros and cons of Vedder’s much-imitated singing style, and which Pearl Jam album he likes most.

InsideHook: I wasn’t surprised that Long Road was smart and insightful, but I was taken aback by how moving it often was. When you were writing the book, did you know it would end up that way?

Steven Hyden: I thought that would be part of it, because part of the story is about the passage of time and things that are able to hang around for a long time. With Pearl Jam, that’s especially relevant — there’s so many bands of their generation that didn’t survive, and that was one of the things I thought was really interesting, because there was definitely a period of time where it seemed like they would implode. There was a common assumption that they were going to self-destruct. Somehow, they were able to avoid that. That just seemed like a fertile topic to think about.

I always feel like, in all the books I write, that there’s an emotional element to it. Sometimes people don’t always pick up on it, which is fine — people take what they want from a book. But that’s what good criticism is — it should be cerebral, but it also should have the emotional element. Especially music writing. I want it to feel like listening to a record — I want it to rock in that same way, I want it to be as emotionally involving in that same way. I’m not saying I hit the mark, but that’s always the goal.

In the chapter about “Sirens,” you write about that 2013 Lightning Bolt track, but you’re really writing about Eddie Vedder embracing getting older — and, in a sense, you yourself getting older.

That’s a song that I would’ve made fun of if I was in my 20s — you listen to the lyrics and it’s about the protagonist of the song being in his house in bed at night and you hear sirens outside your bedroom window, and it makes you feel grateful for the people in your house and that everyone is safe. If I was a guy in my 20s listening to that, I would probably just think that was a lame middle-aged rock song: “What happened to the life-or-death urgency of the early material? This seems very suburban to me.” I’m a little younger than Eddie Vedder, but I have my own family and I’m at a time of life where I feel like those types of concerns — where you’re worried about your loved ones — that is life-or-death, and it actually is more meaningful than a song about a kid who takes his own life in a classroom. These are actual adult concerns.

I think that’s a powerful thing about growing along with an artist in their journey, and that happens a lot with musicians. Any artist that you grow along with and you feel like you’re at a similar time of life as them, you can see how they’re processing experiences that you’re having through their perspective. You can relate to that — that’s a special type of experience.

That was another part of the attraction of this book for me — I was 14 when the first record came out, which made me square in the demographic for what this band was. I’ve written books about artists [where] I didn’t have that experience — I discovered them after the fact, and that has its pleasures, too — but it’s a very unique thing to mature at the same rate that [a band] is maturing.

How does nostalgia factor into this? Do we love the bands we grew up with because they’re good? Or because they came to us at a formative age?

Nostalgia is an interesting thing: That word gets used a lot whenever people talk about art from the past, and it’s always used in a negative sense. There’s a suspicion that if anything that you are talking about has any kind of connection to nostalgia, that isn’t a legitimate feeling or opinion. But when you talk about a band — you could say this about any artist, really, that has a long history — it’s not so much a longing for the past, which is what nostalgia is, as it is connecting you to a version of yourself that may no longer exist.

Maybe people might not see that as a meaningful distinction. But I think about how there’s virtually nothing in my life that I have from the time when I was 14 — maybe the only thing I have are CDs I bought — and there is a value to that that transcends music. It’s something that I try to write about in my books, but it is a little unexplainable, this idea that you become a different person. There’s that thing about how your molecular makeup changes every seven years — all the cells in your body die and they get replaced with other cells. You’re literally a different person over the years. And I just think there’s something valuable about having a foundation that connects you to different versions of yourself. And for me, that’s music. In this book I do a good job — if I can say that about my own book — of not just being a fanboy who loves everything that Pearl Jam did. I have perspective on what works and what doesn’t, but there is something else that goes beyond those aesthetic judgments of art that connects you to not just a past, but your past and your past self.

I think that’s worth examining and it’s worth celebrating. And I feel like that’s something that people intuitively know about art. If you go see a band like Pearl Jam live in 2022, it’s not nostalgia because I think nostalgia [is] an ache for something that’s gone. What people do at a Pearl Jam show is they’re celebrating something that’s still here. Having that foundation in your life, it’s really valuable — I mean, everyone needs that. It might be family or it might be your personal identity, or it might be your connection to a band. We all need to get that from somewhere.

Jakob Dylan on ’90s Nostalgia and “Exit Wounds,” the First Wallflowers Album in Nearly a Decade

The follow-up to 2012’s “Glad All Over” perfectly captures our collective post-pandemic moodYou write about Pearl Jam’s losing battle with Ticketmaster in the mid-1990s over the company’s stranglehold on the concert-ticket business. That Pearl Jam failed to bring about a change demonstrated a death of a certain idealism and anti-corporate mindset of that musical era. In a weird way, it made me think of the poptimism movement, which argues that popular/pop music has as much merit as rock music, which was long considered more artistic and meaningful. In both cases, there was this evolving sense that a band like Pearl Jam needed to lighten up.

I don’t want to get too much into the poptimism thing because it’s really easy to slip into us-versus-them thinking. There’s things I like about that mode of opening up critical conversation to appreciating different types of things where it’s not just dudes playing guitars — I totally support that kind of thing. But in the ‘90s, in retrospect, there was this thing where the biggest bands in the world were also pretty idealistic. There was a nihilistic strain of a lot of music in the early ‘90s — you have the biggest star of that time who takes his own life, that’s like the ultimate nihilism right there. But certainly with Pearl Jam and R.E.M. and U2, some of the big arena bands at the time [thought], “We want to remake rock music and remake the idea of what a rock star is. We want to actually affect positive change in the world and be pretty overt about it.” That was such a common thing with really famous musicians in the early ‘90s.

And then, in the late ‘90s, I think there was a feeling of “Get over yourself, you’re being such a killjoy here. Why can’t we just have fun?” It did feel like we were recalibrating back to the late ‘80s. You have Kid Rock walking around in a fur coat — he would’ve been laughed at in 1993, but in 1999 that was cool again. And I think a lot of people just looked at Pearl Jam at that time as being whiny.

This was brought up recently to me: I hadn’t really considered it when I wrote the book, but nowadays we have a much healthier attitude about mental illness and recognizing [those struggles], and that really didn’t exist in the early ‘90s — or in the ‘90s in general. I think there was this perspective [about] Eddie Vedder that he was this guy who should just appreciate where he is and not be overwhelmed by the circumstances of his celebrity. And I feel like maybe now people would be more understanding of that, [but] back then he was just looked at as this sullen sourpuss.

This isn’t so much covered in Long Road, but Vedder represented a more traditional male-rock-star model — like Robert Plant or Jim Morrison — whereas Kurt Cobain seemed more feminine. I’m curious how you view Vedder’s masculinity in terms of what Pearl Jam represent.

I think that you’re right cosmetically and also just the way his voice sounds — it’s a very masculine archetype that he is continuing. But I think Eddie Vedder was very proactive in counteracting the masculinity of his appearance and vocal style by the way he carried himself in public. [He was] a very vocal supporter of abortion rights and feminism in general — and the way that he wrote songs. On the biggest Pearl Jam records, he’s writing often from the perspective of a female protagonist. The Who notoriously have a very male-centric audience, but I think Pearl Jam’s audience is actually pretty — I don’t want to say evenly split, but they do have a strong female following, probably in part because of Eddie Vedder’s sensitivity to his own masculinity and trying to reconcile that in his music and public-facing persona.

I mean, thinking of other arena rock bands that were selling millions of records at their peak: I can’t think of many examples of the seemingly macho lead singer who is so in touch with his feminine side. And that continues to this day. There was [Mahsa Amini] in Iran who was recently murdered — they’ve been posting a lot about that on Instagram. They’ve been talking a lot about Roe v. Wade. That’s always been a part of what they did. Guns N’ Roses was not doing that at the time.

You write that No Code, a much-maligned Pearl Jam album that wasn’t as beloved as their first three records, is your favorite. It’s also mine, which made me wonder what it is about some music fans that we gravitate to the less-beloved records as a way of sorta marking our territory with a popular band.

Yeah, I think that’s totally true. There’s also the case of being overly familiar with certain records. Ten looms so large in their catalog that you can acknowledge that it’s a great record and also feel like, “I don’t feel excited about listening to it at this point.” Whereas a record like No Code, you feel like you can claim it. It also just feels fresher — there’s no song on that record that has been played a million times on the radio, although “Present Tense” in a way has become this breakout song after it was in the Last Dance documentary [about the Michael Jordan-era Chicago Bulls].

But the other thing I like about No Code is the looseness of it. It feels like a jammier record — I like that side of what Pearl Jam does, especially live. I feel like No Code would actually be a good entry point for people who are curious about Pearl Jam. I think the eccentricity of that record, in a way, has aged better than some of the more straightforward rock records that they put out before that.

That brings to mind something else I wanted to ask, which is where the curious should start if they want to give Pearl Jam a try? Because you rave in the book about their live shows, which you like more than their actual albums, I wondered if you’d suggest a newbie check out a concert first.

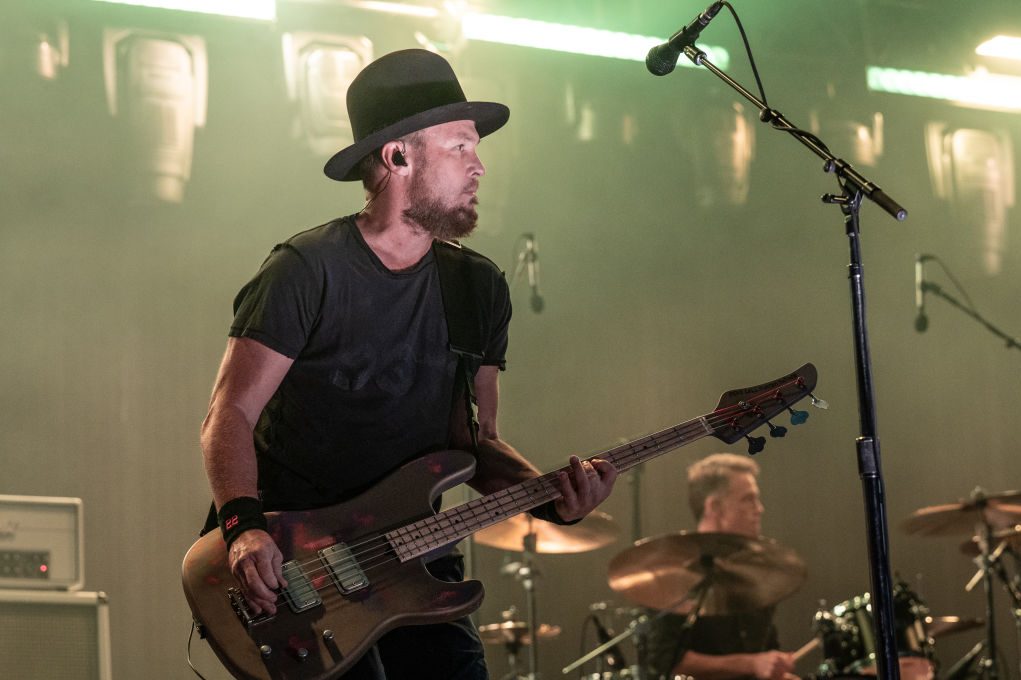

Yeah, I would absolutely say that. I think as an album act, Pearl Jam is a little uneven. Even when they have really good material, I don’t know if they convey it as well on record as they do live. They are one of the great American arena bands of all time — [they] can play those types of rooms and make it feel like a much smaller venue. I think they seem like a lesser band if you are only focused on the recorded material, whereas if you factor in all the live stuff and what they do on stage, I think that’s where they really shine.

Long Road is about the band’s connection to Gen X. Does Pearl Jam mean anything to Millennials or Gen Z?

I don’t get a sense of them transcending the generational divide in the same way that Nirvana has. If I can be grandiose, I would hope that maybe this book can help to rectify that — I tried to write the book in a way that would appeal to, obviously, hardcore fans, but I also wanted that, if you’re just curious about Pearl Jam, you could read the book and it would get you interested in the band.

But Pearl Jam is a quintessential Generation X band because I feel like Generation X has a love/hate relationship with this band. I think Gen X in general is not as boosterish about their own pop culture as other generations are. I think Baby Boomers and Millennials are much more willing to go to bat for the things of their youth — even the garbage of their youth.

You touch on this in the book, where you suggest there’s a tendency in our generation to turn on the music we grew up on.

I feel like a lot of people my age have a lot more affection for the music of the ‘70s than the ‘90s. People my age, if I talk to them about music, [they] love Steely Dan, love the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, stuff like that. But quintessentially ‘90s things are not as embraced by people my age. I think there’s a lot of reasons for that. In the case of Pearl Jam, they were just so popular at their peak and they were popular at a time where culture and media was much smaller — we were all watching MTV, we were reading the same music magazines, and it was easier to get sick of something that seemed ubiquitous. And in the case of Pearl Jam, you could hate them because you saw [them] on MTV all the time. You could hate them because you were more into indie rock, and indie rock seemed — I don’t want to use the word “cool” because that word is overused — but it seemed like a less overheated version of alternative rock.

“Cool” was something I wanted to talk to you about. There are lots of positive adjectives you could attach to Pearl Jam, but “cool” is not one of them. Even at the height of their popularity, they weren’t cool.

It’s funny, someone brought up to me recently [that] Pearl Jam might be the least problematic major rock band ever. Even Kurt Cobain has some skeletons in his closet that don’t get talked about a ton, but Pearl Jam really doesn’t. They’re not a “sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll” band — they are a very ethical band for a band at their level. And that’s been one of their great achievements — that they’ve been able to operate as a DIY band, essentially, while also being a superstar-level rock band.

I mean, coolness as an attribute, it’s obviously something that’s attractive. I like a lot of cool bands — I love the Velvet Underground and the Strokes and Television and whoever else you want to say is cool. But there is also something to be said about music that consciously avoids coolness in the service of emotional connection. And Pearl Jam is definitely that. You can connect them to other historically uncool artists that I think belong on the same continuum — you could say the same thing about Bruce Springsteen.

The attraction of cool music is that it makes the listener feel cool when they’re listening to it. But there are a lot of times in our lives when we don’t feel cool — we feel alienated and lost, and we want something that will help guide us out of that. And cool music will not do that. Uncool music, though, can do that because most of us are not cool — most of us are sort of sad a lot of the time or confused, and there is a value in listening to something that seems to understand that and that’ll make [you] feel less alone.

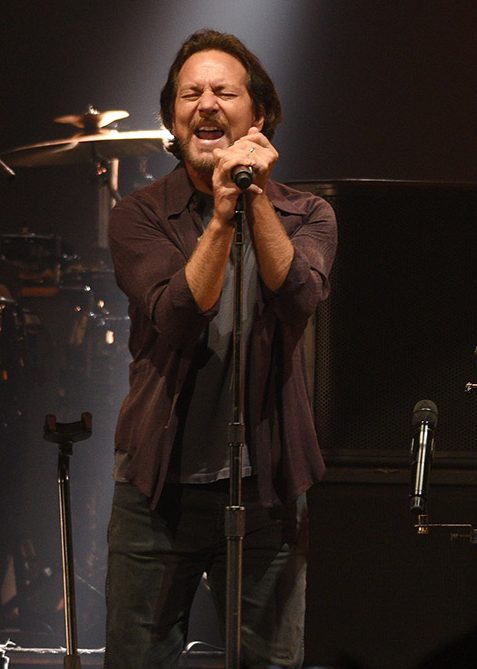

Part of Pearl Jam’s uncoolness is connected to something you talk about in Long Road — Vedder’s earnest, bellowing singing style. As I was reading the book, I was listening to a lot of Pearl Jam, and I kept zeroing in on his singing. It’s so evocative, but also it’s become such a cliché and endlessly mocked. And yet, his voice is a key component of their sonic signature — they can’t escape it.

Well, yes, but it’s also a great benefit to the band. I think that if, say, Andrew Wood had survived and these songs that Stone Gossard wrote ended up being Mother Love Bone songs and it was now Andrew Wood singing “Once” or “Alive,” it wouldn’t have been those songs. They would’ve had different lyrics, but if he had been the singer, I don’t think they would’ve connected in the same way.

Eddie Vedder’s voice has been imitated so many times that it has turned into a cliché, but there’s a reason why it was imitated so many times. It’s because he connects with so many people. This is another cliché, but it does sound like someone singing to himself, even if he’s singing in an arena in front of tens of thousands of people. It sounds like a guy singing at the worst moment of his life.

If you are also having a terrible moment in your life — which I’m sure many people have while listening to Pearl Jam songs — there is a power in that. It’s clear that he has been able to communicate something that’s relatable while also providing a balm. People hear something emotional and real whenever they hear that voice.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.