Jimmy Chin is without question one of the busiest outdoorsman in the world. All while mounting regular climbing trips for brands and personal fulfillment, he has released several projects this year with filmmaker wife Chai Vasarhelyi. The Rescue, their documentary on the Tham Luang cave rescue, was shortlisted for Best Documentary Feature at the Academy Awards, an award they won for Free Solo in 2019. They also executive produced Nirmal Purja’s 14 Peaks: Nothing Is Impossible for Netflix.

On top of that, this year sees the release of Chin’s first photo book There and Back: Photographs from the Edge, a collection of images from several of his epic expeditions. Several chapters are dedicated to his landmark summit of the Shark’s Fin on Meru with Conan Anker and Renan Ozturk. It was a journey that changed life in more ways than one. Below, the 2021 GQ Man of the Year shares the story; it appears as told to Charles Thorp, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

I first started to consider climbing Meru with my friend Conrad Anker back in 2008. He’s been one of my main climbing partners over the last 20 years, as well as a mentor. It is located in the Garhwal Himalayas in Northern India. There is a particular route of the mountain called the Shark’s Fin that had been attempted many times but never conquered. Conrad had tried to climb it before, as well as his own mentor Mugs Stump. The closest that anyone had been was half way. So it had developed a notorious reputation.

I was climbing full-time when Conrad brought it up, shooting campaigns and training a lot. Once we decided to make the attempt I spent time leading up to it doing a lot of what we call “mountain cross training.” Putting your ice axe up on the pull-up bar and lifting yourself up, cranking out reps like that. Doing what you can to cover every single aspect of cardio, endurance, strength. I was getting into full-on beast mode.

I spent the summer running in the Tetons and doing laps on the Grand Teton, which is 7,000 vertical. Getting up early in the morning and doing a lap. I did that to build up my endurance. And then I went to Yosemite, where I climbed El Cap a bunch of times. My systems were dialed in, as far as my rope work and other efficiencies. So all of my skills were in a very good place. I knew that it was going to be a hard climb going into it, but I never realized how difficult it would actually be.

There are a number of factors that make Meru and the Shark’s Fin so difficult. To start, it is at altitude, and while there you need to be able to pull off all of the various disciplines of extreme climbing. As far as disciplines, there is high-altitude climbing, big wall climbing, free climbing, ice climbing, mixed climbing, snow climbing … and this mountain requires them all. Not only that, but it requires you to perform all those disciplines at a high level.

The order of these disciplines is also stacked in this very challenging way. For instance the big wall climbing is at the very top, and for that you need a lot of gear. And the alpine climbing is at the bottom, where you want to be light and quick. That means you have to drag all of this gear that you need later, through this area where ideally you are making fast progress.

Conrad believed that we had the skillset and partnership to have a chance at climbing this peak, though. I had done enough expeditions with him that I knew that I could trust him, and he could trust me. We have a similar threshold for risk. Conrad was our captain, and then we also brought along a slightly less experienced climber with us, Renan Ozturk. He is super talented, and it was a good dynamic that we had built within the team.

Getting there to Meru, and standing in that location, you feel like you are on this other planet. The position of this mountain in the land is completely mind-blowing. The Garhwals are probably one of the most aesthetic and intimidating ranges I have ever been in. Just the sheer magnitude of it all. You don’t do climbs because they are difficult, you do them because they inspire you or they otherwise move you. That is what this climb was to me.

Our first attempt was 20 days long, and we had only seven days of food in our packs. That starts to wear on you when you are doing a lot of intense work every single push. And then we were hit with a huge storm on the way up the mountain. I remember Conrad saying if we were going to make it, we had to be prepared to climb through storms. The only option you have in a storm like that is to hunker down on the mountain. Storms have a way of battering your body but also knocking you off balance mentally. That is why it is so important to go in expecting the worst, so that when it happens, you are ready.

On expeditions food is just about fuel, and about getting those calories. There isn’t a lot of variety when it comes to taste, but we bring a lot of freeze-dried fruits. For a luxury we might have Italian salamis and Parmesan cheese that can survive being at the bottom of a pack. Everything is doused in olive oil, just to add those extra calories. But in the end, we never had enough to last, and we spent the second half pretty malnourished.

We were less than 100 meters away from the summit when we were forced to turn back. It was utterly heartbreaking. We had pushed through so much to get that far. There were many times we had made a decision that we were only going so much longer, because we were entering a whole new risk scenario and then we would go past it. Time and time again. That is what made having to turn back so painful.

We had decided that we were going to go back try to climb the Shark’s Fin again before we even made it back to the ground below Meru. We were rappelling down in the middle of the night, talking about what we should have done differently and what gear we were going to bring the next time. We were beaten up, starving, but already planning on coming back. The next attempt ended up happening in 2011.

I had been shooting throughout that first attempt, but the technology improved by the time we were setting up the second one. Because we were sacrificing room in our packs that could be used for other gear, I couldn’t bring infinite batteries or media cards. I had no way to back up. I had to be very deliberate with my shots. There were some technological advances by this time, like the Canon 5D came out. That meant I was able to shoot stills and video with the same camera. It offered this much more cinematic look.

By the time we returned to the mountain we were really dialed in. The main changes we wanted to make was to trim down the weight on the packs and to bring warmer sleeping bags. The ones we had brought for the first attempt were meant for the summer and we had been sleeping in below-20-degree temperatures. We also brought warmer boots.

I trained pretty much the same way for the second one, but the great advantage we had this time around was that we had seen 99 percent of the mountain. The first time we had gone in blind on the second half. We all gave it all we had and more. It started to dawn on us that we were going to have to go way beyond our boundaries if we were going to make it to the top.

Summits are great. They are even better when they took a few attempts, because you put that much more into them. There were a few moments that stick out in my mind about that trip, but the one in particular is when Renan Ozturk was on the summit and he is just having a moment. He starts to give this little monologue on how grateful he is and everything that we have been through to get to this summit. I was filming it, and I couldn’t help but think that it would make an incredible end to a film.

The descent from Shark’s Fin was also really tough and intense. That is the case with the descents after most big climbs because you have put everything into getting to the top. You are absolutely smoked by that time. If you look at the statistics, most accidents happen on those descents, because you are exhausted and you haven’t eaten in days. We had one of our closest calls on the descent. There was a big rock fall that came down during this one section that we have aptly named the “Shooting Gallery.” Our group had just crossed as the rocks started to come down, we missed it by five minutes.

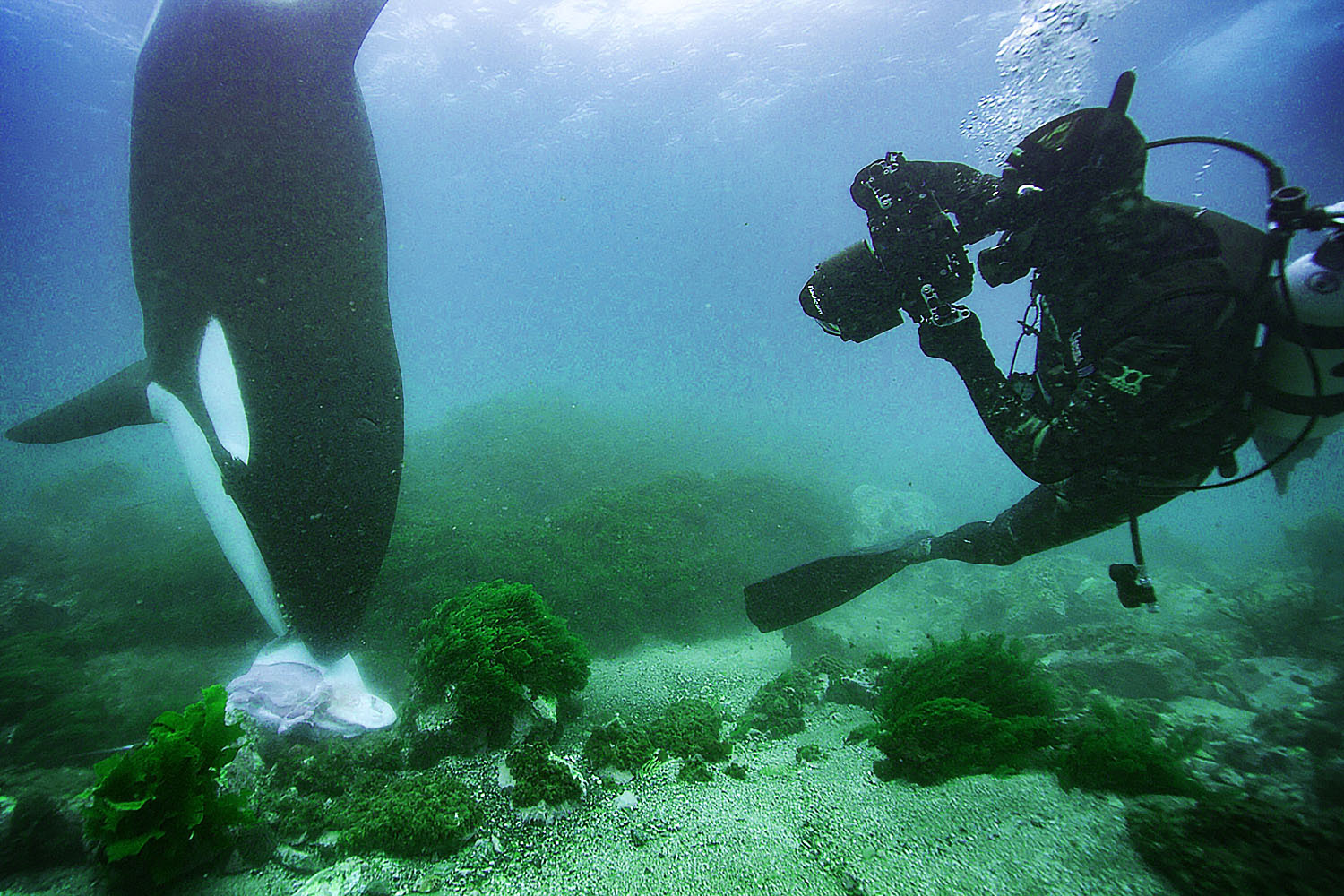

Expedition shooting is what I consider the purist form of what I do. It is that intersection between being a climber or an alpinist and a photographer or filmmaker. That is the sweet spot for me, probably because it is the most challenging and it forces me to be 100 percent present. I had to learn to force myself to pull the camera out at the times I least wanted to. It can be difficult to shoot a movie when you are in full-on survival mode.

I started to look at the footage all together and could see that there was a story there, bigger than the climb itself. I saw this greater story about friendship and mentorship. I saw a way that I could help people understand why we do these dangerous climbs. I met my wife Chai while making the documentary. She was already an accomplished filmmaker. I knew that authenticity I was bringing to the story, but she brought this whole other level of storytelling and craft to what I was doing.

The documentary ended up being rejected by Sundance twice, so in that way it was like the climb itself, except this time it took three attempts and not just two. But when it got accepted, we won the audience award, and then got a distribution deal. It ultimately ended up moving a lot of people, and helped get us our funding for what would be our next film, Free Solo.

I learned a lot on Meru. Both in my climbing and in my filmmaking. I learned what it is like to fail, and then come back stronger than before. I was a lot more confident on the other side of this experience. Every time you push it that far, you come back down with a better understand of what it is like up there and how to assess situations correctly. I used a lot of what I learned about working with a lean team on Meru when it came time filming Alex Honnold’s climb of El Cap.

Check out more of Jimmy’s photography here.

This series is done in partnership with the Great Adventures podcast hosted by Charles Thorp. Check out new and past episodes on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts from. Past guests include Bear Grylls, Andrew Zimmern, Chris Burkard, NASA astronauts, Navy SEALs and many others.

For more travel news, tips and inspo, sign up for InsideHook's weekly travel newsletter, The Journey.