While I try to spend as little time as possible thinking about Kevin Spacey these days, there is one aspect of American Beauty that I often think back on. Suburban sad-sack Lester Burnham feels trapped in his humdrum life, until a crush on his daughter’s hot friend (a different time, 1999!) prompts the reality-shattering realization that he can reenergize himself with the simple resolution to do so. In practice, this mostly means smoking weed and lifting weights in his garage. This strikes me as a rather comforting notion, that no matter how locked in to the menial rhythms of adulthood one might be, there’s an easy and immediate way to renew enthusiasm and appreciation for the everyday. It was not long into my teen years before I realized why my father, a man fitting the approximate description of Lester Burnham minus the lechery, would declare this his favorite movie.

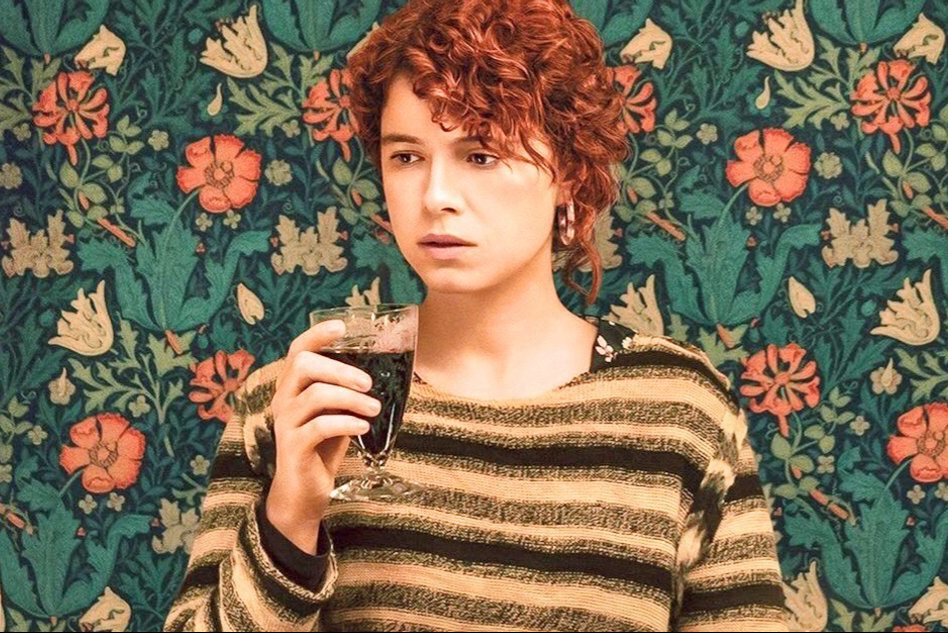

Thomas Vinterberg’s rollicking new film Another Round stretches this idea to its breaking point, with marijuana replaced by buckets upon barrels of booze. Though afterschool specials love to trumpet the evils of “gateway drugs” leading to harder stuff, alcohol has more frequently served as a gateway to more alcohol, which then opens up to a slope made slippery by a steady flow of wine, beer and spirits. For the quartet of fortysomethings who embark upon an unusual regimen of constant imbibing, they see the cruising altitude they maintain all day long as the secret to youth and maybe even enlightenment — better living through sozzled neurochemistry. What makes the film a comedy is that they must painstakingly learn the lessons we can see coming a mile away, their arrogance and self-absorption blinding them to the eternal truth that getting wasted is only fun until it’s not. No one stops drinking when they’re at the ideal level of inebriation; we only know to call it a night once things start to feel bad, by which point we are of course too late.

For men worried about their masculine bona fides as they approach middle age, there’s nothing more humbling to be than an educator. History instructor Martin (Mads Mikkelsen), phys-ed coach Tommy (Thomas Bo Larsen), psychology teacher Nikolaj (Magnus Millang) and choir director Peter (Lars Ranthe) must all contend with the cruelty of time as they get older while class after class of pupils remain the same age. They’re surrounded by virile young men and women, the glorious teenage abandon a depressing contrast with the spouses, kids or post-divorce solitude they have waiting for them at home. More humiliating still, they can’t shake the old line about teaching being a job for those who can’t do, each one skilled enough to do their chosen work but only at the grade-school level. “Have I gotten boring?” Martin asks his wife, her response indicating that he’s more concerned about this than she is.

Over dinner to celebrate the big 4-0 for Nikolaj, Martin tells his friends of an intriguing article he recently read in which the author posits that the brain’s natural blood alcohol content is slightly negative. The idea is that a human being could unlock their full potential by being one or two drinks deep at all times, leading to latent wellsprings of confidence and creativity. Any other bunch of friends would laugh this off, but this clique’s ennui and aspirations to academia combine in a setup all but guaranteeing calamity. They decide to give this a whirl, but rationalize their attempt to perk up their monotonous lives as research, laying out their plans for controlled profligacy as an experiment complete with the sort of unwieldy title that published papers always seem to have. To us, they are clearly deluding themselves. They will take a little longer to arrive at this realization.

With a little discipline and moderation, perhaps a constant .05% BAC could be made into a workable lifestyle. In the first phase, when the men adhere to the guidelines they’ve set for themselves — no drinking on nights or weekends, no exceeding the recommended dosage during the day — the results are positive. Martin engages his disinterested students with a bit of Hitler humor, Peter improves his singers by drawing the curtains for total darkness and Tommy leads an ungainly moppet called “Specs” to his first goal in soccer. They come to believe that they’re the best versions of themselves while buzzed, one of many alcoholics’ refrains the men will echo during their escalating bender. Other tracks on that greatest hits collection include “I Can Stop Any Time I Want,” “Who Put That Wall There?” and “Sorry for Urinating on That.”

The emotional subtext of what they keep insisting is an intellectual exercise comes out once Martin makes the classic drunk-brained error of syllogizing that if the drinks he’s had thus far have made him feel this good, more drinks will be even gooder. They begin to torpedo their personal lives, with Martin’s wife admitting to an indiscretion as a last-ditch effort to shock him out of his stupor. But they ultimately get what they want, regressing past the prime they were aiming for and landing closer to infancy. Nikolaj’s little son has nightly bed-wetting issues, forming an ironic rhyme with his papa’s similar incident at his rock bottom. And yet for all their childlike tendencies when three sheets to the wind, these men inevitably reach the universal conclusion that nothing makes a person seem older than trying to appear young.

Director-cowriter VInterberg makes a wise move and slips right in between the two expected conclusions for the film, neither releasing Martin and his pals from their self-destruction as fully reformed cases nor sending them into a spiral of dissolution. After severing ties with his wife, the de facto protagonist Martin does manage to dry out and turn a corner, and the final scene offers him a chance to get his old life back. Faced with the prospect of returning to the domestic drudgery he left behind, he instantly reverts to his old ways and starts chugging champagne with a passing gaggle of recent grads. He’s locked in a pattern known far too well to so many men his age, cycling through resentment for the stifling home he takes for granted and devastated longing once he sees how good he had it.

He makes such clear bad decisions — the viewers can watch everything he holds dear crumble in slow motion — that Vinterberg needs to remind us of what he’s been chasing this whole time. He bids Martin farewell at the juncture of pure transcendence that comes before his next downfall, intoxicated with an ecstasy he expresses through a surprisingly limber jazz-ballet dance among the youths. He runs and jetées like he doesn’t have a care in the world, though we all know this high can’t last. The last shot of the film, as indelible as any you’ll find, freezes on Mikkelsen’s black-suited body as he flings himself from the dock where everyone’s partying into the waters of the harbor below. The camera fulfills his dream of suspending himself in that moment, freed from the onward march of time that leaves us all wrinkly and hung over. For one second, in that perfect tipsiness that makes a man feel charming to invincible, Martin thinks he can defy the laws of nature. He can’t be getting older if he’s going to live forever.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.