I am not a violent person.

Sure, I had a few scraps as a kid. And I was jumped once, on Bourbon Street. But I don’t seek out violence, and I don’t live in fear of it.

At the moment, however, things are a little different.

I am standing in the dark. A train roars by in the distance. Suddenly, a man wearing a helmet yells something as he lunges forward at me. He reaches for my head and I strike him repeatedly between the eyes with the side of my hand, using his forward momentum against him. He falls hard and fast. That’s when I notice a knife, which he had been holding, tumble to the ground.

I stop fighting and yell for help.

This is when the simulation ends, but it sure doesn’t feel that way. My hand hurts. My heart is racing.

A voice calls out: “Box!”

I move into a square on the floor.

The voice yells again: “Hood!”

A cylindrical column made of black polyfibers drops over my head. I’m wearing a helmet that smells like musty football gear. My tormentors ready themselves for round two.

The hood is raised and a new guy is standing adjacent me. He kindly asks for directions to the freeway. I can’t tell if he’s a threat. He’s big and wearing the same clothes as the last guy, but I can’t see his face. I don’t know where the freeway is. He steps closer and I tell him to step back, that he’s making me uncomfortable. He puts his hands up and says “OK.” I tell him that I don’t know where the freeway is and he backs away.

The voice calls out again: “Box!”

I step back into the square on the floor; the hood is lowered again.

One round I’m in an altercation, the next, I’m assisting someone with directions, or someone is asking for help, or someone asks me for directions and then attacks me. Again and again, I’m faced with stressful situations that require split-second decision making. I have no idea what’s next, but I have to dial back my emotions to meet whatever is on the other side of the hood.

***

Like I said, I’m not a violent person. But when I was invited to spend a day at the new West Coast training facility for Duane Dieter’s Close Quarters Defense, aka CQD, I signed right up. (The training runs from $1,000 a day, but the organizers were nice enough to host InsideHook for free.) CQD is the tactical training taught to Navy SEALs. Until recently, it was not offered to civilians. I took an abbreviated version of the program at Sports Academy, a state-of-the-art training facility for pro and amateur athletes in Thousand Oaks, California.

Athletes — like people in combat scenarios — often have trouble checking their emotions, which is why Sports Academy owner Chad Faulkner reached out to Dieter the first place. After learning about CQD on a Young Presidents Organization trip, he realized it might help players keep their heads under pressure, so he convinced Dieter to offer the class at Sports Academy. They brought in Angel Naves to supervise the program.

Unlike other self-defense and tactical classes out there — and there are more of them every day — CQD abides a series of tenets, the most critical of which is teaching participants how to control their emotions and reactions under extreme stress. They call it dialing, and whether you’re under fire from a gun-wielding terrorist or assisting the family of a suicide victim, it involves essentially the same measures: remaining in control, and, critically, identifying your purpose within a split second. It’s as important for you to be able to dial up intensity as it is for you to dial it down, and the simulations I just recounted are meant to create muscle memory that you can carry with you beyond the program, whether you’re defending your family or dealing with work issues.

The classes are meant to instill in you a critical edge, which they hone through a series of simulations which are monitored, taped and then reviewed so that you get real-time feedback and validation. The benefits go beyond not losing your cool. It sharpens your awareness and fine-tunes your purpose. It also builds confidence.

Prior to the simulation, I spent two hours in a large, padded-walled room learning the history and practice of CQD from Angel Naves, the former SEAL and SEAL instructor who heads up the program at Sports Academy. He cuts the figure you’d imagine of a retired SEAL: over six feet tall, muscular, hawkish. He even wears black fatigues. In conversation, he has the elocution of a Silicon Valley CEO. But when he’s instructing you, he takes on the disposition of a personal trainer, addressing you with pithy endearments in between barked commands: There you go, daddy-o. Regardless, he’s effective.

The principles of CQD are simple to learn. They rely on kinetics and physics, and have a basis in various martial arts disciplines. And they work. During the simulation, I used the methods to defend myself in simulations with the SA staff, one of whom was a former professional baseball player and considerably bigger and stronger than me.

CQD was developed by Duane Dieter back in the mid ‘80s. At the time, he was living in Baltimore. One night, he was attacked.

“I was standing in the street near some buildings waiting for some friends,” he told me. “The person who attacked me was standing beside me, and with no reason for me to think he was aggressive.”

Dieter held black belts in various martial arts at the time, but during that altercation, he didn’t have time to use his training.

“I saw the flash of a fist and at that same moment I deflected his fist, he kept engaging. I was younger and more physical and was able to best him, but after it was over, and it was really quick, I realized that I didn’t get in my stances, didn’t do my high kicks or anything like that. It was faster than I could think. That’s the key that changed my life.”

The altercation taught Dieter that the formalities of martial arts are rarely practiced on the street. There’s no bowing. No time to assume a combat stance. Things happen quickly. That realization left Dieter determined to learn how to defend himself in the case of a criminal attack. Dieter says he traveled to Hong Kong, Taiwan and Okinawa seeking a master who could impart the ancient fighting knowledge he was seeking. Eventually, he found the perfect mentor, an 81-year-old martial arts master who offered him a key insight: he told Dieter he needed to find the answers for himself.

And so, Dieter did.

“I started focusing on the criminal — that’s the high-risk type of attack,” he recalls. “I eliminated all of the theories of the sport and established tenets: use force only for the purpose of defending oneself or those that are preyed upon; use only the force that’s appropriate; and only use it when I knew for certain that it would work in an engagement in which someone was motivated to do me or someone else harm.”

He tested his theories out with friends. They developed a rudimentary version of the hood I experienced during my training session — a pillowcase — and took turns attacking one another, trying to create the sort of high-stress situation one encounters out in the world.

“It became that same feeling,” he says of the simulations. “I couldn’t comprehend or get in my stance or make a kick or strike, because it was that fast. As a police officer or as a citizen, very often a person attacks you and you’re not prepared. If you were prepared, you could escape, which is something we teach.”

He tested his reactions over and over, having others watch him to help improve his results.

It was around this time that he started working for the Drug Enforcement Agency Task Force, and they soon began adopting Dieter’s tactics, which by then included the use of guns and other weapons.

In 1989, he was approached by the Naval Strategic Warfare Defense Group, which you may now know as SEAL Team 6. “They saw [CQD] as very important to them,” he recalls. By 1991, he was training the SEALS. Eventually, he opened a 300-acre facility in Vienna, Maryland, equipped with an array of gun ranges and tac houses.

After 9/11, Dieter’s CQD was adopted by the Secret Service, the CIA, the State Department and other federal branches of law enforcement.

“They’ve all gone through the training with the hood and situational training — what we call iso-tacs — which trains for small incidents,” he says. “And then we go to the Tac House, in which there can be as many as 200–250 role-players, from attackers down to officers on the street. It still all starts with their individual core competency, which is what you went through, so you know that you went through that attack under duress and could stop the attack if necessary.”

In recent years, many government agencies have moved away from CQD in favor of somewhat controversial MMA-style tactics that Dieter says are more violent.

“MMA is a great sport with many exceptional athletes, and we have had many MMA participants go through our training,” he says. “Naval Special Warfare has utilized CQD as the only approved and adopted training system for the SEALs for over 20 years. Through their own words, verified on official documentation, senior leader guidance and over 10,000 positive critiques, the SEALs themselves recognized that CQD was the best training system available and directly related to their missions, giving them a distinct advantage over the terrorists.”

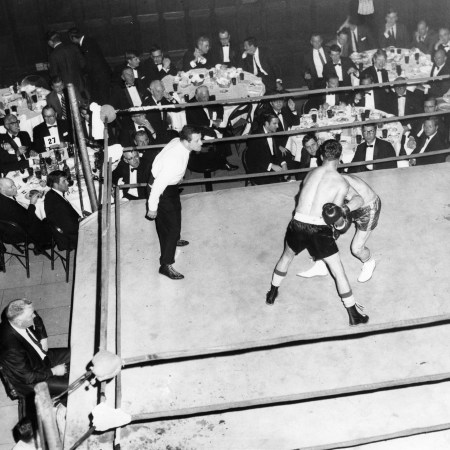

MMA training is less codified than CQD. It also has a different intention in mind — entertainment via hand-to-hand combat, with a referee present to break up the action if things go over the line — which means it isn’t ideal for training military or police operatives. “No operational requirement exists for MMA,” says Dieter. “It is a sport, designed for the sport arena.”

Eventually, Dieter began offering his course to professional athletes and high-profile public figures: people who often find themselves confronted by strangers and need to defend themselves without escalating minor scuffles into full-blown TMZ episodes. They also train wealthy individuals and their families, bodyguards and law enforcement.

Whether you’re a SEAL or a civilian, the tactics are the same. This hit me when Naves was teaching me firearm tactics and instructed me to keep my finger off of the trigger.

“I thought the SEALs went in to kill?” I half-joked.

He shook his head. “We go in to take prisoners,” he said. “You can’t get intel from a dead guy, and if you kill someone’s family member, you make an enemy for life.”

This is where dialing comes in — and the reason Dieter is now training police departments throughout Maryland. Given the spate of questionable shootings involving police around the country, CQD is well-positioned to help officers maintain self-control in high-adrenaline situations.

“Law officers today have a more refined challenge: to be better and more precise in their force control as well as be a better example for the community,” Dieter tells me. “They have cameras on the officers all of the time, which we appreciate and like, because it does capture what happens.”

***

Back in the training room at Sports Academy, Naves tells me to strike the pad he’s holding up. Then he tells me to shout out commands:

You’re making me uncomfortable. Please back up. Put the gun down. You’re doing fine.

These dialogues are suited to various circumstances you could find yourself in as a law enforcement officer — or as a civilian. We do it over and over to develop a core competency: the goal is to stop the person before they become a threat. Dieter says CQD training for cops involves a lot of this, which they term “soft-talking.” He believes cops need to strive to be “kind and considerate” and do “nothing to escalate the situation but constantly working to diffuse it.”

These are the rhythms that people in many high-pressure fields face, from law enforcement to CEOs: one second you’re in an intense situation, the next you’re expected to be thoughtful and compassionate.

Dieter tells me, “Because the training allows you to react to the situation, which we call flows and dialing, each second has to be correct. One second you could be defending yourself, and the next you could be providing treatment for the person beside [the perpetrator] that they’ve just shot. You could be helping a small child deal with the trauma, helping a family deal with a suicide, all of these are things that people are dealing with. The officer needs to know he has the full-circle approach to what could happen to him. More than any other group in the world, he has to deal with the threats. Then he has to be able to go home and dial down and not let those difficult things that happen in his workplace affect his family.”

All of the simulations at Sports Academy are videotaped, so that participants can see if they’ve acted appropriately — defending when necessary, attacking when necessary and dialing back when, as is often the case, the threat actually isn’t there at all.

“Some people can dial down super well but they can’t dial up,” Dieter says. “And they need to be able to dial up to survive in an intense moment.” He continues. “It’s the balance. It’s that confidence. It’s putting the stress on the person and taking it off. That’s why after all of these years, I’m so concerned about the quality of the program. If someone was going to get these types of theories and push them too far to the right or to the left, it may not be in balance.”

During my second round of simulations, Angel introduces a new element: guns. I’m in the waiting room wearing an oversized canvas shirt, goggles and a neckguard, because we’ll be using Simunition FX — live rounds of marked pellets — which sting if you’re hit but don’t do any lasting damage. After the simulation, they’ll let us know who was shot.

I’m fairly terrified. I force myself to relax, because I don’t want to appear scared, but I just can’t sit still. I’m sweating. Eventually, Angel opens the door and I go into the safe room before going into the vaunted hooded box.

As I stand there, nerves jangling, the hood flies up. A guy fires at me. I promptly return fire, and he goes down. I yell for him to move away from his gun and flip onto his stomach. He doesn’t comply. I shoot him and he stops moving.

Box!

I go back to the box and the hood is dropped over my head.

Hood!

The hood goes up, and there’s a man on my left asking for help and another person behind him with a gun. As I level my gun at the armed assailant, I tell the person asking for directions to get on the ground for safety. Then I yell at the gunman to drop the weapon and get on the ground. He does as I say. I direct him to lie on his belly and turn away from the gun. He complies. I tell him to cross his legs and turn his head away from me.

Box!

These simulations go on for 30 minutes, until Angel pulls up my hood and tells me the exercise is over. But I don’t want it to be over: it’s exhilarating.

I am not a violent person.

But in this moment, I grasp for the first time why there are so many violent people around me. And why now more than ever, we — me, you, police officers, the justly accused, the unjustly — need tools to help us better negotiate situations like the ones I had just confronted.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.